Last Updated:

UPDATE (Dec 10):

The Fed restarts Reserve Management Purchases with USD 40 billion monthly purchases

The Fed announced after their December meeting that it will purchase “Treasury bills and, if needed, other Treasury securities with remaining maturities of 3 years or less to maintain an ample level of reserves.”

New York Fed in a separate statement announcing that it will kick off the RMP program with a monthly Treasury bills purchase amount of USD 40 billion starting Dec 12.

- Subsequent monthly purchase amount “will be announced on or around the ninth business day of each month,”

- The pace of RMPs will “remain elevated for a few months” as the New York Fed plans to offset an “expected large increases in non-reserve liabilities in April,”

- After that, the pace of purchases “will likely be significantly reduced” to meet “expected seasonal patterns in Federal Reserve liabilities.”

What is the Reserve Management Purchases?

Reserve Management Purchases (RMP) is a form of open market operations under which the Federal Reserve injects reserves into the banking system through “permanent” asset purchases with an aim to ensure the level of reserves remain “ample“.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York President John Williams brought back the concept in his mid-November speech, saying it is “the natural next stage of the implementation of the FOMC’s ample reserves strategy.” It “will not be long” before the “ample” level is reached, Williams said back then, implying that RMP will be launched soon.

RMP is not QE

Reserve Management Purchases is not Quantitative Easing. They are two different kinds of central bank operations.

RMP is supposed to be a technical fix to prevent the level of reserves from falling further when other liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet, such as currency in circulation, continue to grow and drag down the amount of reserves available in the system. It is not supposed to have any monetary stimulus effect as it is just a technical tweak to keep enough liquidity in the financial system.

QE, on the other hand, is designed to provide an economic boost through active purchases of longer-term Treasuries by the central bank. By buying a significant amount of long-term government bonds, the central bank can help compress long-term risk-free interest rates and stimulate investment in the real economy. Similarly, central bank acquisition of assets such as mortgage-backed securities and corporate bonds are extensions to the QE strategy, providing a targeted boost to the housing sector and corporate bond market.

Last time the Fed engaged in RMP

The Fed’s most recent experience with RMP was in Oct 2019, right after the so-called repo crisis a month earlier. The US central bank decided to buy USD 60 billion of treasury bills a month “at least into the second quarter of [2020] to maintain over time ample reserve balances at or above the level that prevailed in early September 2019.”

The operation was later disrupted by the COVID pandemic, which triggered a restart of QE in March 2020, making the experience of RMP a short-lived one. The COVID QE made it difficult to gauge the effectiveness of RMP in any comprehensive way.

Moreover, the Fed in the post-2019 repo crisis also engaged in a substantial repo operations, with a mix of overnight and term repo, to inject even more reserves into the system.

RMP means the Fed is committed to supply-driven-driven floor system

In the QE era, the Fed relies on two administered rates—Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) and Overnight Reverse Repo (ON RRP) rate—to control overnight interest rates in the market. This is the so-called “floor system“.

As there is far more liquidity than banks demanded, the overnight interest rates tend to fall toward zero. However, by allowing banks and money market funds to earn interest by depositing extra liquidity at the Fed, these administered rates create a floor below which financial firms have no incentive to lend to peers.

Recently, central banks like Bank of England and the European Central Bank have adopted a variation known as the “demand-driven floor system.” In this framework, the central bank shifts the primary channel of reserve creation from permanent asset purchases to repo transactions. These central banks have established repo facilities that allow financial firms to borrow as much as liquidity as they need against collateral, effectively letting the market determine the optimal level of reserves supply.

While the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility has the potential to function as a demand-driven tool, the Fed’s determination to opt for RMP—which is a form of “permanent” asset purchases—indicates a commitment to a “supply-driven floor system.” This means the Fed, rather than the banking sector, will determine the growth of reserve supply. Under this system, the Fed must estimate the optimal RMP amount to accommodate both liquidity demand fluctuations and the reserve-draining effects of other balance sheet liabilities.

Does the repo market signal a need for RMP?

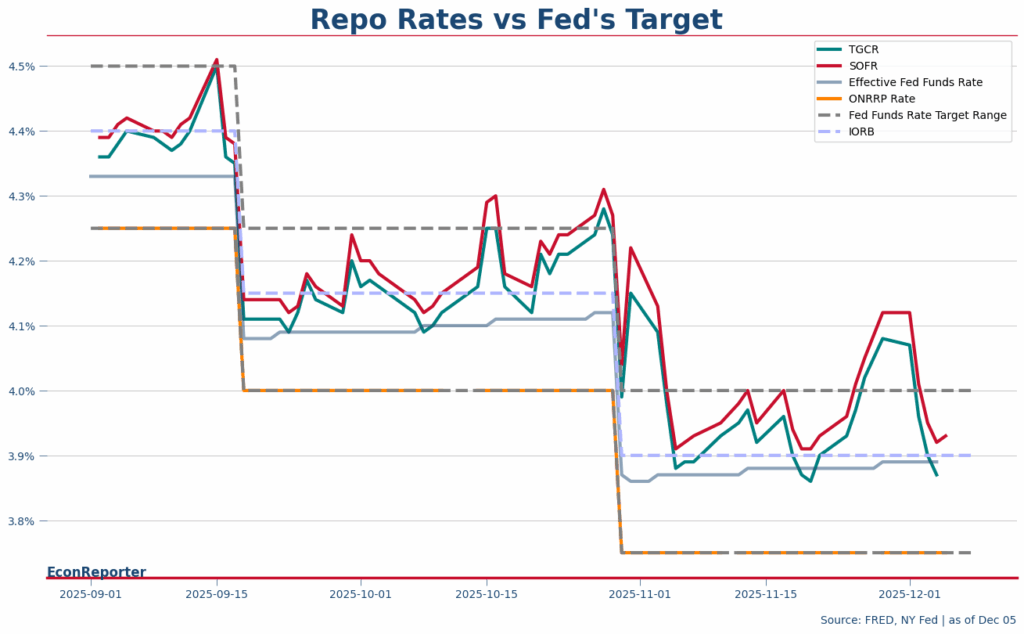

The repo rates—both the Tri-party general collateral rate and SOFR—rose above the Fed’s interest rate target upper limit at the end of November and the start of December. This continues the so-called “leaky ceiling” problem as the Fed can’t contain repo rates from shooting above its target.

However, ever since the government shutdown ended and the amount the US Treasury deposits in its General Account at the Fed started falling again, the repo rates were mostly staying within the Fed’s overnight interest rate target range. For example, on Dec 5, the SOFR rate dropped down below the IORB level (which was set at 3.9%), which is a behavior consistent with “ample” reserve regime.

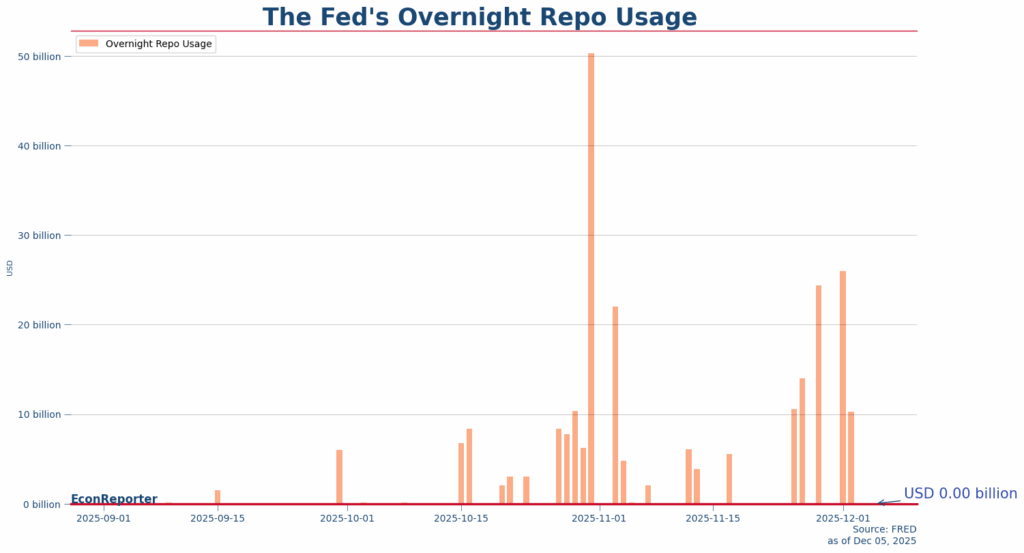

SRF usage also dropped to close to zero late last week, when the month-end effect dissipated. These readings indicates that in “normal” days, the level of liquidity in the system is still at the “ample” region. There is no immediate danger of losing control over short-term interest rates.

The Fed can simply look through the period-end effect, saying it is mostly a regulatory issue which limits dealers’ balance sheet capacity in these dates, with a potential partial solution of adding central clearing to the SRF.

Still, this is why the Fed will restart RMP at Dec meeting

However, we can also look at the other side of the coin and argue that the late October experiences also suggested that the Fed may only have USD 50 billion-100 billion buffer before the repo rates become volatile again—as we saw the Treasury General Account fell from USD 984 billion to USD 909 billion while reserve rose from USD 2,828 billion to USD 2,878 billion.

So, while I would argue the current repo market behavior doesn’t warrant a panic reengagement of RMP, it is still reasonable for the Fed to put the trigger on January just to thicken the buffer above “ample.” As the Fed is obviously opting for a supply-driven floor system, having a larger buffer zone can ensure better interest rate control. The downsides are also likely limited at the margin: the interbank market won’t be rejuvenated either way and the SRF won’t be used extensively one way or the other.

If the Fed chooses to use a bit more excessive liquidity in the system, RMP is definitely the way to make sure repo rates won’t go crazy and harm financial stability. This is why the Fed would announce RMP in the upcoming meeting.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡