Last Updated:

“The [Standing Repo Facility (SRF)] rate is set at the top of the FOMC’s target range for the federal funds rate. This combination of an ample supply of reserves and an SRF rate at the top of the target range reduces the day-to-day reliance on the facility except during periods of significant upward pressure on rates resulting from strong liquidity demand or market stress,” said John Williams, President of the Federal Bank of New York, in a speech Friday. (emphasis ours)

This line doesn’t get as much media attention as his other passage, which says “the next step” of the Fed’s balance sheet strategy will be “to assess when the level of reserves has reached ample. It will then be time to begin the process of gradual purchases of assets,” as people mostly care about when the Fed will start the “non-QE QE”, as Vítor Constâncio, former Vice President of the ECB called it.

But the stated preference to “reduces the day-to-day reliance on” the SRF is telling because, as we have argued before, the usage of this overnight secured lending facility at the Fed is not sufficient to make it an effective interest rate ceiling tool.

Williams basically rejected this line of argument. The SRF is not to be used daily, he said. It is not a liquidity provision tool; It is a liquidity backstop.

Liquidity Provision vs. Liquidity Backstop

The differences between liquidity provision tool and liquidity backstop are subtle. But thanks to the European Central Bank’s Conference on Money Markets last week, they were made a bit clearer in the speeches from Williams, ECB’s Isabel Schnabel and Bank of England’s Victoria Saporta—the official representatives of each central bank’s interest rate and balance sheet strategies.

Both the ECB and BoE have stated their intentions to adopt a so-called demand-driven or repo-led floor system. That is, they will switch to a reserve-supply regime that is based on repo transactions, as opposed to asset purchases by the central bank.

Banks would use their high-quality asset holdings, such as government bonds, as collateral to exchange for central bank-created reserves. The amount of reserves to be supplied in the financial system will then be largely determined by the amount of liquidity the banks requested through these repo transactions; hence, the system is demand-driven, instead of a supply-driven model under which the central bank solely determined the amount.

The interest rate ceiling tool in a demand-driven model has to be a liquidity provision facility also—it is because the way to keep the overnight interest rate within the central bank’s control is to give the banks all the reserves they need. For the system and the facility to work efficiently, the central bank would cut the amount of reserves way below the so-called “ample” level, forcing the banks to engage with (or even rely on) the liquidity provision tool to get enough reserves for their daily operations.

As Schnabel put it in her speech, “[i]n a demand-driven framework, the central bank’s operations are not a liquidity backstop. They are there to be used by banks as part of their day-to-day liquidity management”

The Fed’s “Above Ample” Philosophy

The Federal Reserve, however, is not adopting a demand-driven model, as emphasized by Williams; which is why the US central bank can characterize the SRF as a liquidity backstop instead.

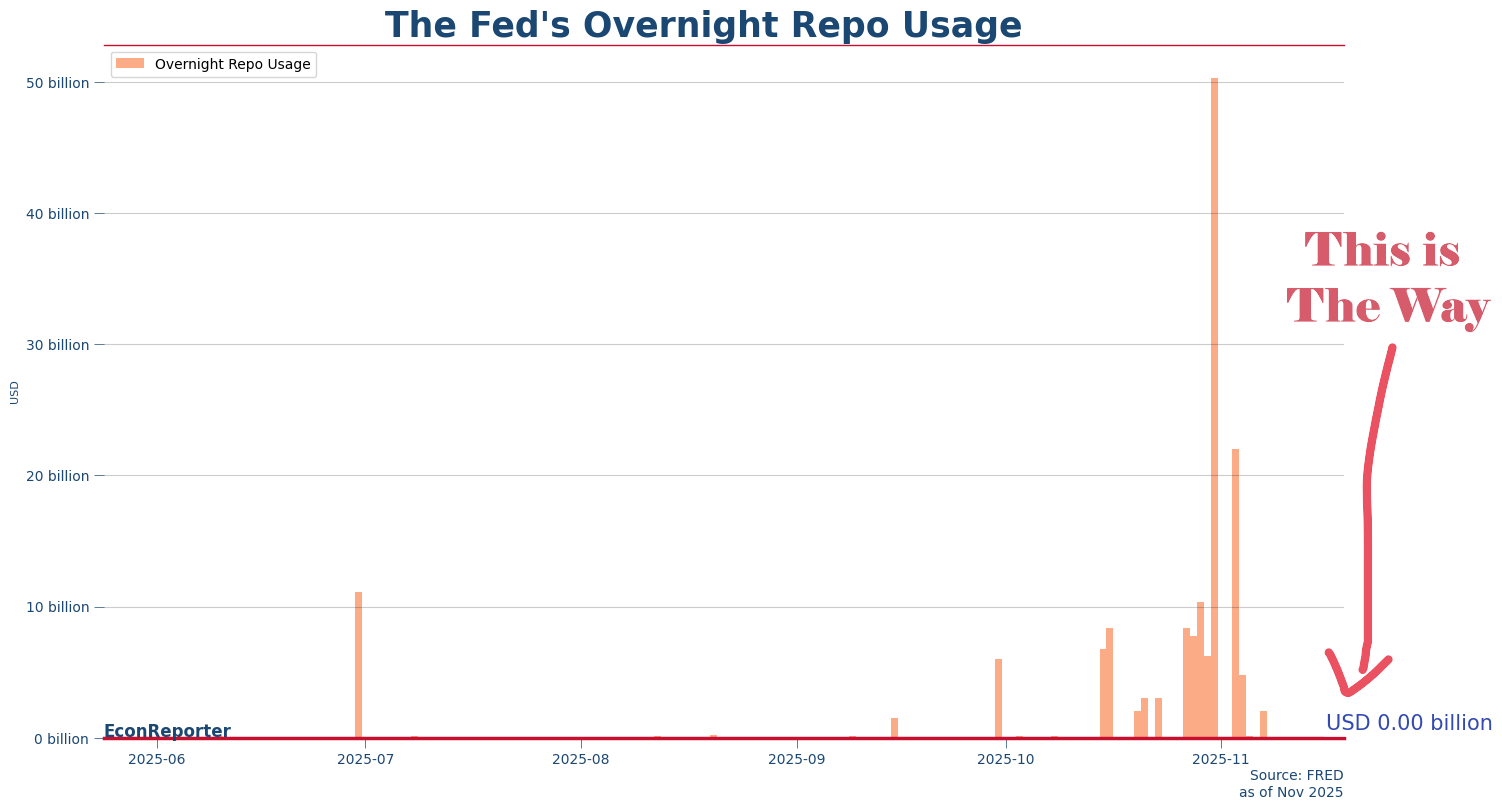

It is also why the current usage of SRF, which is filled with days when the facility were barely used, can said to be “working as intended.”

The Fed likes to project that their strategy is to maintain the level of reserves at a level that is above the “ample” level, so they would like to keep the reserve supply from shrinking, or at least slow the pace of any further reduction, whenever the repo rates start to spike.

This is the philosophy behind the Fed’s “sudden” end of quantitative tightening (QT) last month (The Fed’s QT has not yet ended, to be clear. It will end by the end of November.) Any sustained spike is a sign that level of reserves may be too close to ample, in the sense that the buffer above ample is too thin. Without a thick enough buffer, the SRF will have to be deployed more often than the Fed desires and risks turning it into a day-to-day liquidity supply source.

SRF is not Designed as a Liquidity Provision Tool

But why shouldn’t the banks rely on SRF day-to-day? One simple explanation is that the SRF is not designed to be an effective liquidity provision tool.

In his speech, Williams mentioned the BoE’s Short-Term Repo facility (STR), which booked an average usage of GBP 85 billion in October, amounting to about 13% of the reserves the BoE supplied. It is substantially higher than the less than USD 5 billion average usage of the SRF in the same month, which represented less than 0.2% of the reserves in the US system.

But the BoE’s STR is different from the Fed’s SRF in certain substantial ways. One of them is the duration of the repo: STR holds a weekly auction to provide 7-day liquidity through repo transaction; SRF, meanwhile, provides overnight liquidity through daily operations.

This is a huge difference in the sense that it can be logistically costly and inefficient to provide a significant amount of liquidity in the most important money market in the world through daily overnight repo operation and tell the banks to roll over the loans every day.

In contrast, a repo operation with a slightly longer term can reduce the operational costs and can give the market a relatively stable supply environment. For example, the ECB’s main refinancing operations, its main short-term tool, is also a one-week financing tool.

“[I]t would not be prudent for a central bank to rely exclusively on short-term refinancing operations. Concentrating liquidity provision in just one instrument would give rise to operational risks and encumber a significant amount of collateral,” as Schnabel explained, in describing the ECB system.

Which is also why, in both the ECB and BoE’s system, they set up another so-called “long-term” liquidity provision tool to create reserves for banks to satisfy their more stable and predictable part of liquidity demand.

In the UK, the tool is called Indexed Long-Term Repo and it lends out reserves in the form of 6-month repo; In the Eurozone, they call it “structural operations” in general but the details are still to be determined. As Schnabel explained, these term repos will likely be in the form of regular longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) with a tenor of less than a year.

SRF as a “Supplementary” Discount Window

Then, why haven’t the Fed installed any kind of term repo facility yet? This again reflects the Fed’s rejection of installing any liquidity provision tool. But the US central bank is definitely no stranger to term repo operations. In fact, the 2019 repo crisis was in part contained through a series of term repo operations (with tenors that ranged from 2-day to 42-day).

Ever since the SRF was established, term repo has no longer been on the menu.

But the SRF is actually set up in a way resembling the discount window, which is also a liquidity backstop, rather than the liquidity provision facility the Fed deployed to counter the 2019 repo crisis.

As the discount window and the SRF are priced at the same rate, both at the upper limit of the Fed’s Fed Funds Rate target, currently 4%. It is not a surprise that Fed officials recently have to keep reminding banks of the supposed differences between the two facilities.

“The SRF plays a critical role in capping temporary upward pressure on rates and assures markets of effective interest rate control and smooth market functioning. It is best thought of as a way of making sure that the overall market has adequate liquidity consistent with the FOMC’s desired level of interest rates. In that regard, it differs from other lending facilities—such as the discount window—that aim to provide individual banks with liquidity when the need arises,” Williams explained. (emphasis ours)

In this sense, the Fed has installed two liquidity backstops. The SRF is the one to support the overall market liquidity level; and, the discount window is the one to provide a temporary bridge for an individual bank to handle its own liquidity trouble.

This also means that the SRF is in essence a supplementary discount window. It is a necessary tool to make sure the market won’t be short of liquidity due to legacy stigma concerns about using the discount window.

Demand-Driven Model is Not Panacea

One last point I would like to tackle here is the question of whether a liquidity provision tool is a better solution to rate spikes compared to a liquidity backstop like SRF?

Not necessarily, as the UK’s recent experience can attest.

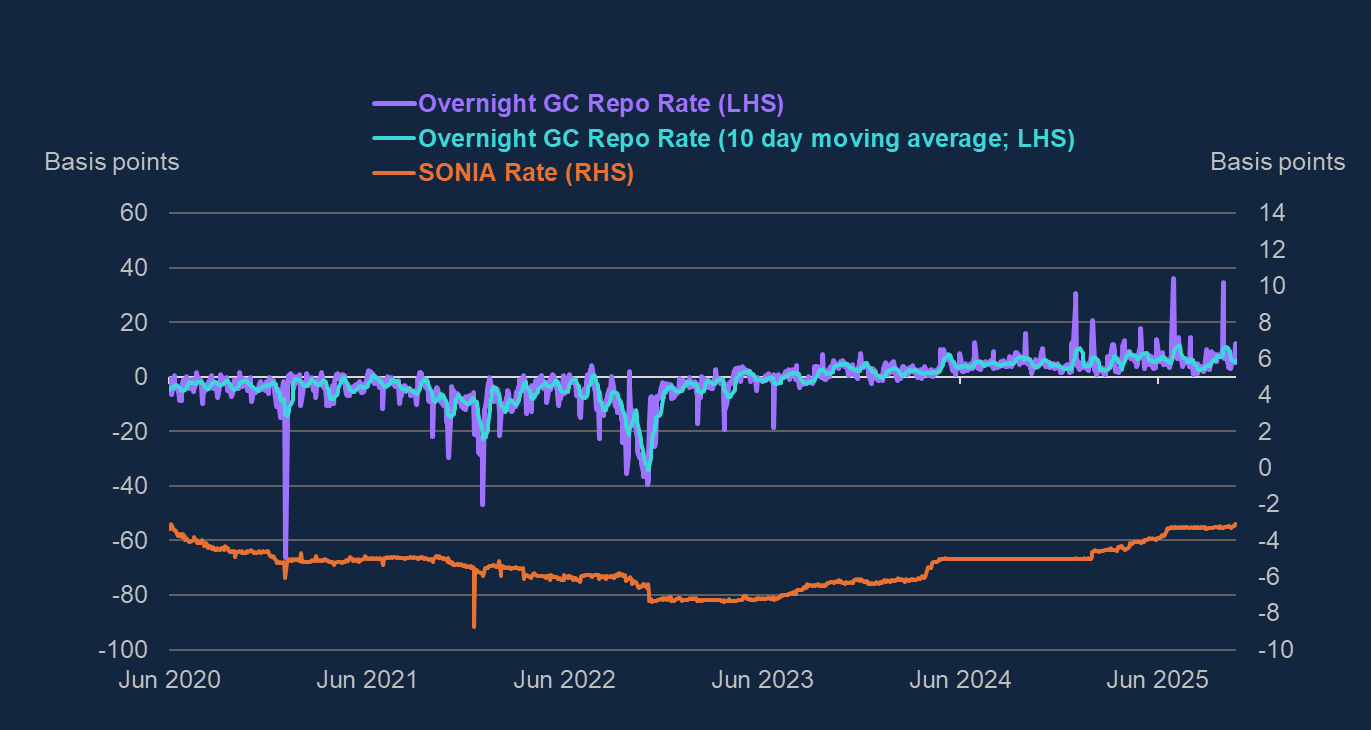

As shown by the below chart attached in a speech by Victoria Saporta, the BoE’s Executive Director for Markets, overnight repo rates continued to spike every period-end, despite significant usage of STR and ILTR. The extent of these spikes are sometimes quite substantial, reaching 40 bps in some cases.

Saporta still categorized the situation as a success, as she views this as “evidence that the STR facility is playing its role in preventing more persistent rises in repo rates.”

But she also added that “elastic central bank reserves supply is not a panacea,” referring to the situation that out-of-control repo rate shoot-ups can have financial stability implications as more non-bank financial firms rely on repo market financing.

“An elastic and well-designed central bank operating framework is a necessary and sufficient condition for monetary control, but not so for financial stability,” said Saporta.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡