Last Updated:

Standing Repo Facility (SRF) is a relatively young Federal Reserve facility.

Formally established as a permanent tool in July 2021, SRF allows banks to obtain overnight liquidity with high-quality collaterals like Treasuries through a repurchase agreement (repo).

Most people may not be familiar with this “obscure” Fed tool, but it is possible that SRF will soon become one of the Fed’s most important tools.

The Origins of Standing Repo Facility

SRF is designed as the Fed’s ultimate response to the interest rate spikes that plagued the money market in 2019.

The US central bank started its first-ever quantitative tightening (QT) program in Oct 2017 and in Jan 2019 formally adopted the so-called “ample” level, a minimum level of reserves necessary for the Fed to maintain interest rate control without active interventions, as its stated destination.

In the second half of 2019, as the reserve balances in the system had been substantially reduced, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) started to rise above the Fed’s interest rate target range. It caught the market and the central bank by surprise with how quickly the “ample” level was seemingly reached.

“‘Geez, the Fed’s going to step in, right? The Fed’s going to step in, right? They are, right?’ People were expecting the Fed to step in,” said David Andolfatto, chair of University of Miami’s Department of Economics and a former Senior Vice President at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, referring to a sentiment a contact in the private sector once described to him.

Andolfatto was one of the earliest advocates for the Fed to establish a Standing Repo Facility. In March 2019, he and Jane Ihrig, a senior advisor at the Federal Reserve Board and was then visiting at the St Louis Fed, wrote “Why the Fed Should Create a Standing Repo Facility” laying out the case for SRF.

“Economists frequently make the statement that price discovery is important, it is an important function in allocating resources,” explained Andolfatto. “This is not what’s happening during these repo spikes. This is just pure panic speculation. This should not be happening.”

A solution to this problem, he and Ihrig suggested, was to set up a facility that lets financial institutions use their high-quality collateral, US Treasury securities in particular, to access the liquidity they need. With a repo facility in place, financial institutions would not need to sell their high-quality assets in time of general market stress.

Andolfatto and Ihrig then wrote a follow-up explainer on their ideal Standing Repo Facility setup in April, and the idea gained more popularity online and at the financial sector. “People in the industry were going, ‘Wow, now the Fed’s going to implement a Standing Repo Facility!'” recalled Andolfatto.

“Whereas in reality, inside the Fed, it was kind of, ‘No, we don’t need this.'”

The situation changed when the Fed briefly lost control of repo rates in September. September 17, 2019, to be precise. One that day, the SOFR rate spiked to 5.25% when the upper limit of the Fed interest rate target was 2.25%.

Another special thing about that day? It was the first day of the year’s sixth FOMC meeting.

“I was there with Jim Bullard (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis president at the time), Neel Kashkari (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis president) and his research director, Mark Wright, at the time. The four of us were in the van going to the FOMC meeting that morning, the morning of the repo tantrum,” Andolfatto recalled, “Jim and I were in the back, Kashkari and Mark were in the front, and then the driver turned the news on. The news is coming on and it’s talking about the repo tantrum. I remember Kashkari turned back to me, and said, ‘Gee, I guess your repo facility would have been a good idea.'”

On the second day of the FOMC meeting, Bullard asked a pivotal question: “If we had a repo facility to complement the reverse repo facility, would that solve this problem, or would we still have the same kind of volatility?” according to the Fed’s meeting transcript. Standing Repo Facility at that point became a serious topic of discussion in subsequent FOMC meetings.

With hindsight, New York Fed economists attributed the causes of the Sept 2019 repo market dislocation as “a sharp temporary decline in reserves, substantial Treasury securities settlements, and a corporate tax date,” according to the Reserve Bank’s blog post.

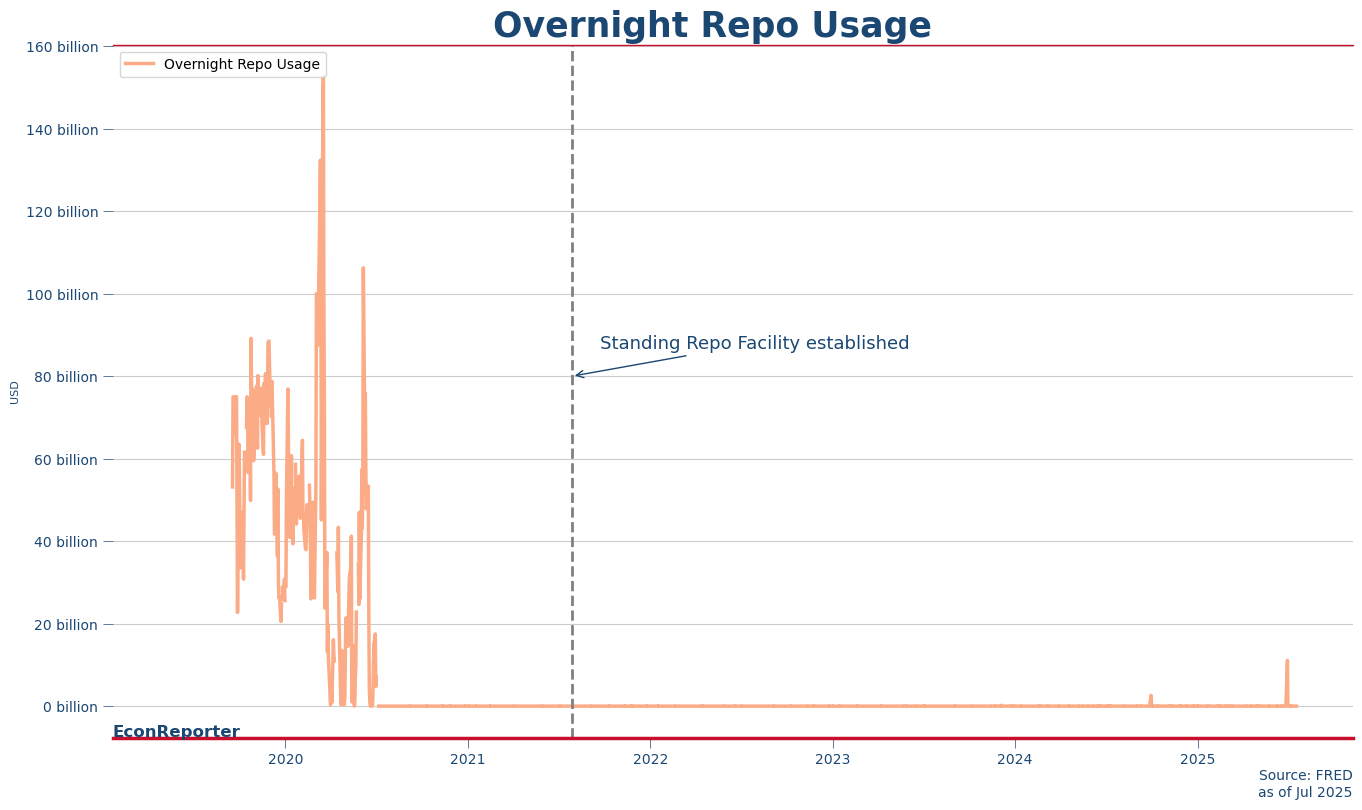

To contain the repo crisis, the Fed first adopted standardize repo operations to supply additional liquidity to the market. Then, the Covid pandemic hit in March 2020, the Fed had to restart QE to support the economy, which flooded the market with liquidity again. As the reserve level became abundant again, banks no longer had the need to draw liquidity from temporary repo operations or SRF. The Fed’s repo toolkits were mostly left unused since July 2020.

SRF was only formally established in July 2021. June 30, 2025 was the first time since then that the SRF lent out more than USD 10 billion in one day.

Standing Repo Facility as an interest rate ceiling tool

For the Fed, Standing Repo Facility is mostly regarded as a backstop facility by the Fed and “is only intended to be used intermittently when stress emerges in funding markets and overnight interest rates are pressured higher”, according to a 2022 explainer by the New York Fed.

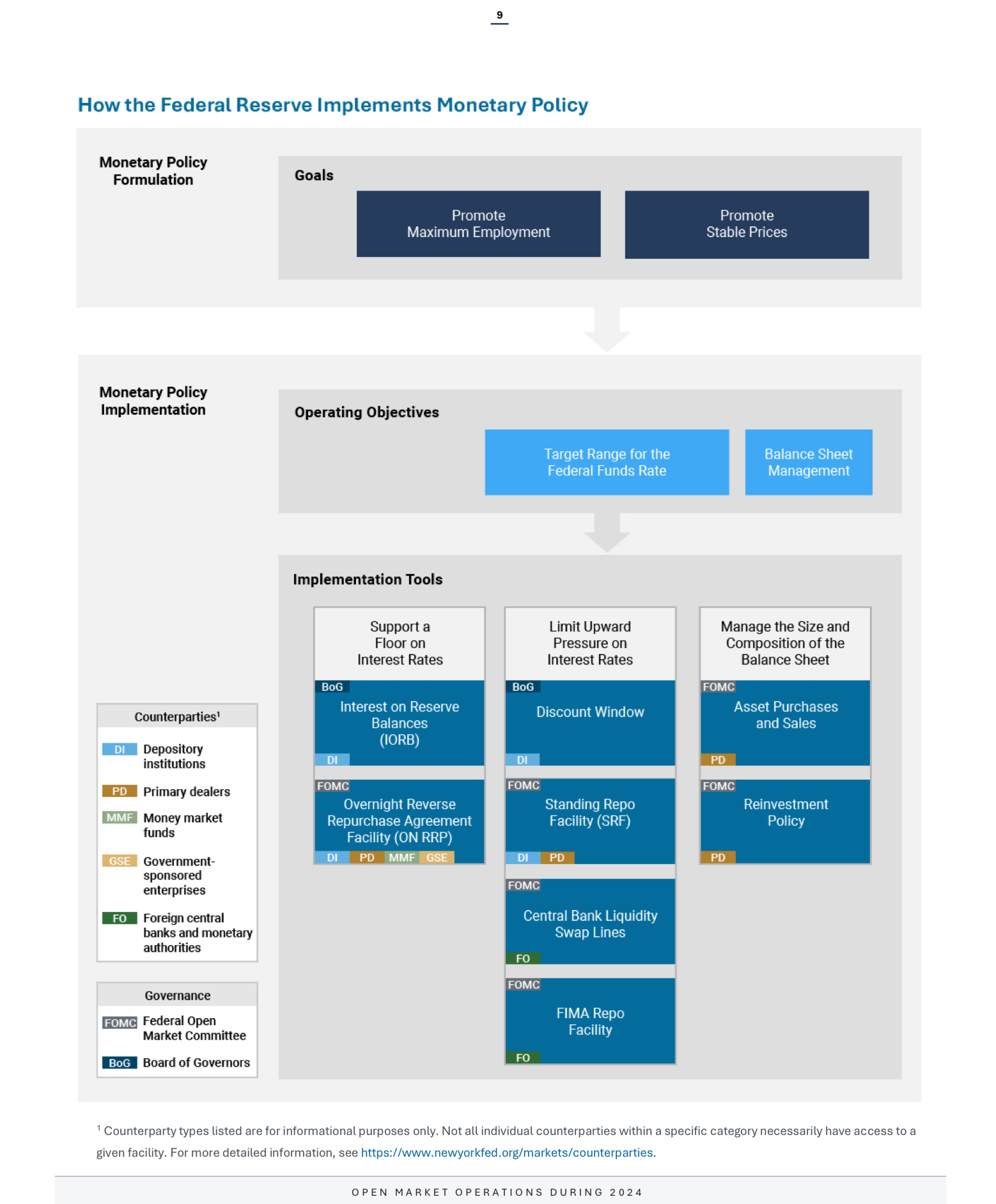

Standing Repo Facility is designed as an interest rate ceiling tool alongside the Discount Window, which has historically been the Fed’s lender of last resort tool to prevent banks from suffering liquidity shortfall in times of crisis. But they are different in two major ways.

First, the Discount Window takes a wide range of securities as collateral, including corporate bonds and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs); the SRF, meanwhile, only accepts a selected set of high-quality liquid assets, including US Treasuries, agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities.

Another difference is the size of the facility. Discount Window provides “ready access to funding” for banks with no specific limit. But for the SRF, there is a USD 500 billion daily operation limit, which is now shared by the two auction sessions, one in the morning (around 8:30 am) and another in the afternoon (around 1:30pm). (Adding a morning auction in the SRF from June 28 is one of the Fed’s recent initiative to encourage usage for the lending tool.)

Box 1: Explainer on the post-QE reserve demand and supply

One major effect of QE is that it changed how central banks conduct their interest rate policy.

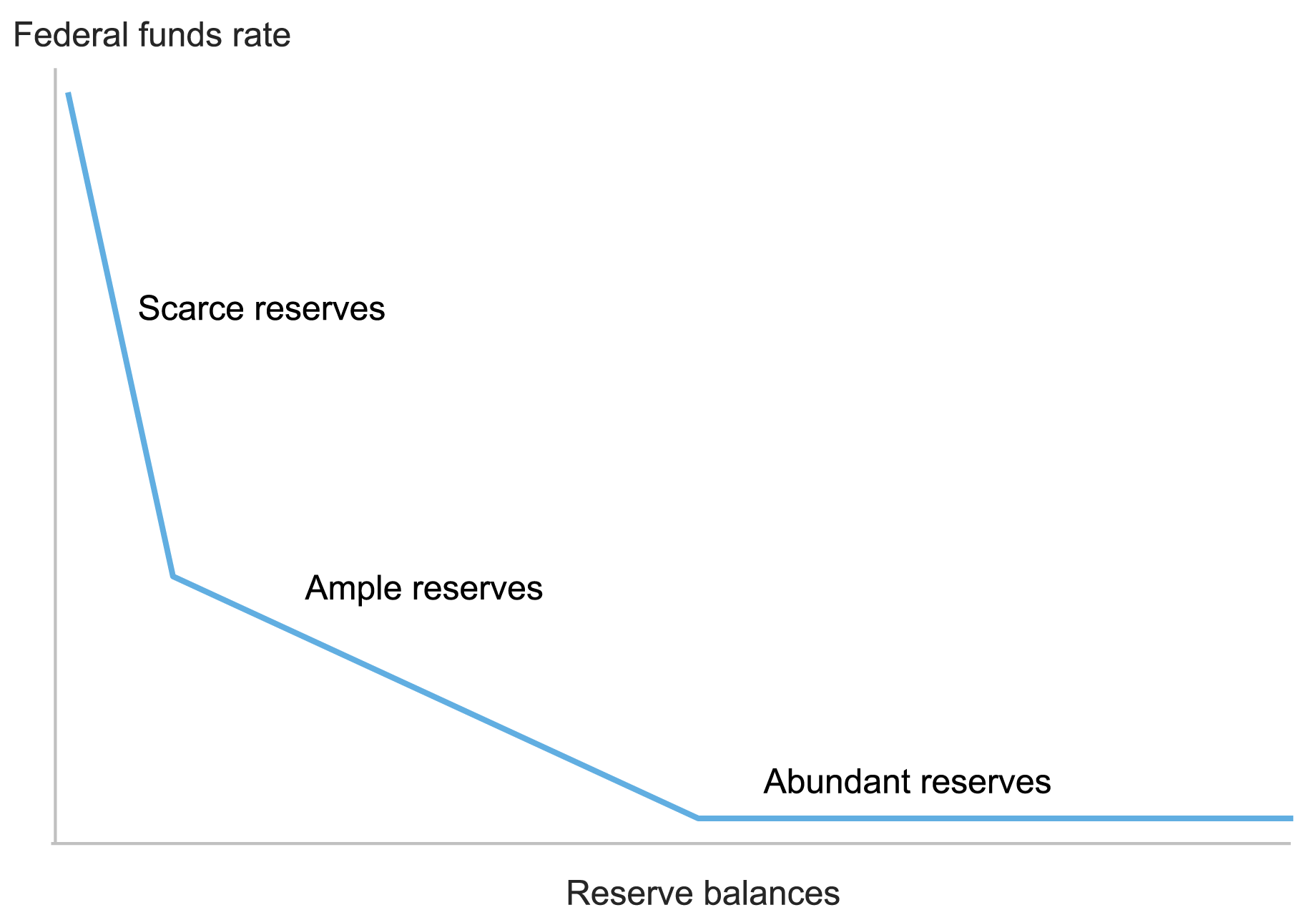

Take US as an example: before QE the Fed adopted a scarce reserve system.

- The central bank had to adjust daily the level of reserves in the banking system to match shifts in reserve demand and maintain fed funds rate at its target.

- This setup is also called corridor system, with interest on excess reserves as the floor and discount rate as the ceiling. The fed funds rate could fluctuate within this range, requiring the Fed to adjust reserve supply to guide the overnight rate toward its policy target.

QE—through which the Fed bought long-term Treasuries and other securities like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) with newly created reserves—flooded the banking system with a never before seen amount of reserve supply. This pushed the fed funds rate down to the floor of the interest rate corridor.

This is when the Fed shifted to the so-called floor system, or more officially an “abundant” reserve system. Its primary interest rate control tool became the interest on excess reserves (later redefined as interest on reserve balance, IORB, as all reserve became interest-bearing).

- Because the excessive level of reserves pinned the fed funds rate to a level close to IORB, the Fed can then guide the overnight interest rate by ratcheting IOBR up and down.

Since not all money market participants have access to the fed funds market, overnight rates in money market and fed funds rate tends to fall below the IORB.

- The Fed, therefore, employed overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP) as a complementary tool to ensure fed funds rate stays close to its policy target.

- Money market funds can deposit their liquidity into ON RRP. Since these funds then have the option of receiving ON RRP rate or lending the money out to other counterparties to earn prevailing money market rate, arbitrage tends to align the two rates, making the ON RRP a supplementary floor for the fed funds rate.

What is “ample” level of reserve?

Ample level of reserves is best explained using a reserve demand graph from the New York Fed. According to the Reserve Bank’s characterization, ample reserves is a special zone where further contraction of reserve supply begins to raise fed funds rate, but not significantly.

- It is described as the minimum amount of available reserve required to keep floor system operational without needing daily tweaks to reserve supply to match changes in reserve demand, as was common in the scarce-reserve era.

The End of QT is near. What Next?

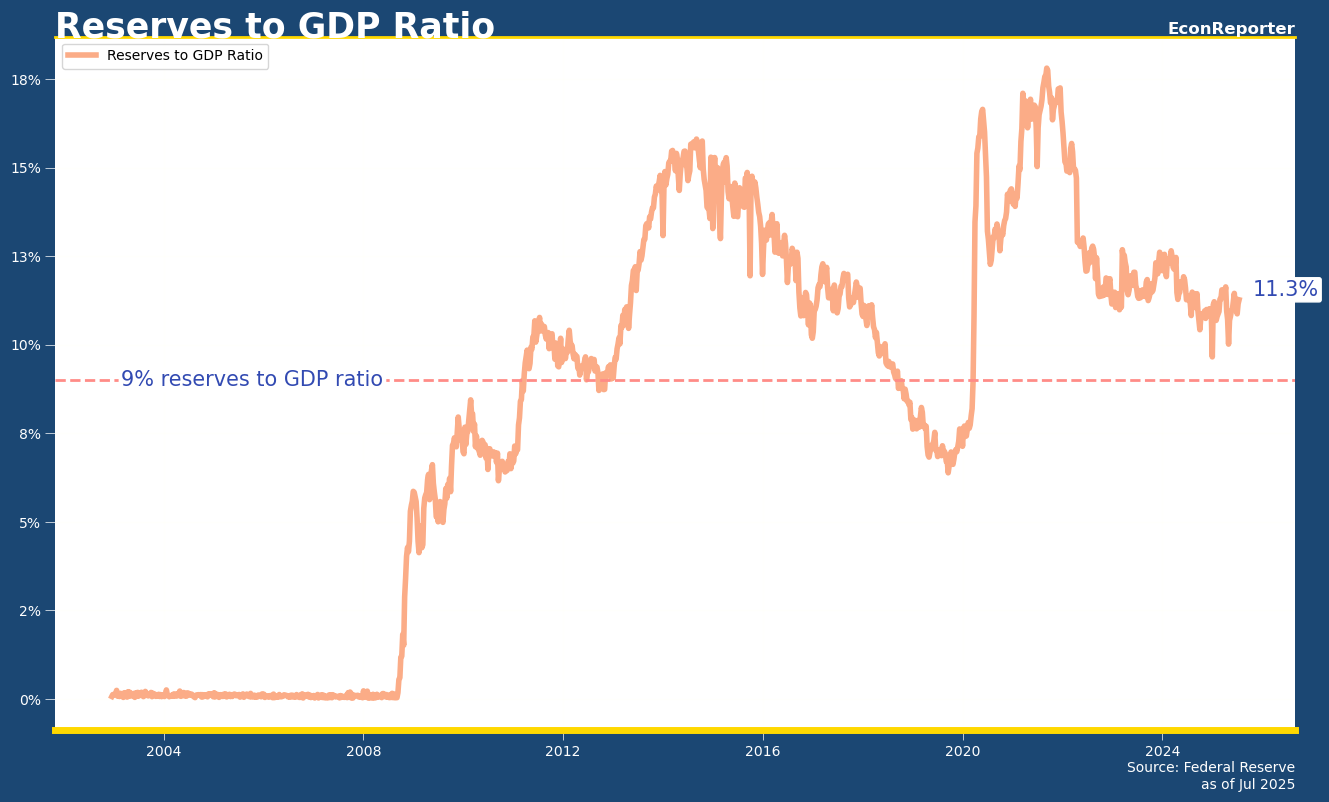

The FOMC in June 2022 began its second round of QT to again normalize the size of its balance sheet. As the reserve supply contracts, it is edging back to the ample level.

Governor Chris Waller this month argued that QT should be stopped when the ratio of reserve to US (real) GDP drops to 9% to avoid a repeat of the 2019 crisis; that roughly translates to a reserve level of USD 2.7 trillion, around 600 billion lower than the current level of USD 3.3 trillion.

With the end of QT in sight, “the SRF is likely to be more important for rate control than it has been in the recent past,” proclaimed Roberto Perli, manager of the New York Fed’s System Open Market Account (SOMA) and who is responsible for implementing FOMC’s monetary policy decisions, in a speech in May.

The Fed’s current plan for post-QT monetary policy is, more or less, to reach an ample level of reserves and then stay there. “[But] it’s never going to be as easy as they think,” said David Beckworth, Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center of George Mason University and host of Macro Musings Podcast. “They would say, ‘Well, we don’t have to forecast reserve demand.’ But you do have to forecast whether you’re on the ‘ample’ part or not, and we really don’t know that until it actually happens.”

In a way, “ample” is a concept that is clear on paper but can be quite hard to observe in real time. Sort of like the concept of “neutral rate” — an interest rate level at which inflation is neither accelerating nor decelerating — central bankers can always try their best in estimating where the ample level is, but no one can ever know for sure. Liquidity demand always shifts, as it’s affected by many real-world factors.

To their credit, the New York Fed has developed a tool called Reserve Demand Elasticity (RDE) to measure how sensitive Federal Funds Rate is to reductions in reserves. If RDE estimate turns negative and is significantly different from zero, it indicates that reserve demand is leaving the “abundant” region and moving into the “ample” level.

Standing Repo as the star of Demand-driven Floor System

Other major central banks have another idea. Bank of England, European Central Bank and Reserve Bank of Australia are all contemplating an idea called demand-driven floor system.

The basic principle for a “demand-driven” system is similar to the Fed’s ample framework: reduce the amount of reserves in their financial systems to a level very close to the minimum needed to keep the floor system operational; but then instead of trying to “stay there” by managing reserve supply themselves, the central banks let the banks decide the amount of reserves to be poured into the system through repo transactions.

Take BoE’s framework as an example. The UK central bank set up a facility called Short-Term Repo (STR) for banks to borrow reserves for one week with high-quality collateral; The interest rate the BoE charges is at the same level as the Bank Rate, its policy rate. This way, banks’ liquidity demand can create matching temporary reserve supply through the STR, effectively giving the control of overall reserve level to banks and the money market — hence, it’s called “demand-driven” system.

“This is why I think a demand-driven system is better because you don’t have to know, right? In a demand-driven system, when the banks need something, they’ll let you know. But with a true supply-driven floor system where the central bank pushes out the reserves on their own, you don’t know if that’s too much or too little,” Beckworth explained.

Standing Repo Facility has the potential to be the STR equivalent in the US. “Demand-driven repos (also) constitute a key part of our framework here at the Fed, most notably in the form of the SRF,” Perli mentioned in May. That is to say, the Fed can potentially allow banks to obtain the liquidity they need through the SRF once the overall reserve supply falls below “ample”, making SRF a regular liquidity provision tool; i.e. the central part of a US version of demand-driven floor system.

Nonetheless, quite a number of design choices are making the SRF poor candidate to be the star of a demand-driven system.

First of all, SRF has a daily lending limit of USD 500 billion; short-term repo operations under central banks that adopted demand driven system all promise “full allotment”, i.e. financial institutions can borrow as much as they want at the stated pricing.

A guaranteed full allocation is important for a repo-led reserve supplying system as liquidity demand can sometimes be extremely volatile, as happened in Sept 2019. A limited-size operation means the Fed risks not providing enough reserves to the market on the days they are needed the most. This could hurt market confidence in their ability to contain serious repo crisis.

Perli in May mentioned that “[t]he uncertainty of award allocations, which is related to the size limits of the facility” is also one of the major frictions that discourage financial firms to use SRF.

“What are these limitations on the allotments? You have to free up the size of the balance sheet and you have to expand access to a larger set of counterparties if you’re serious about interest rate control,” said Andolfatto.

The types of participants allowed are another major potential issue for SRF to be effective. Currently, Standing Repo Facility is only open to Primary Dealers and depository institutions, which comprise mostly banks, largest investment banks and securities broker-dealer firms.

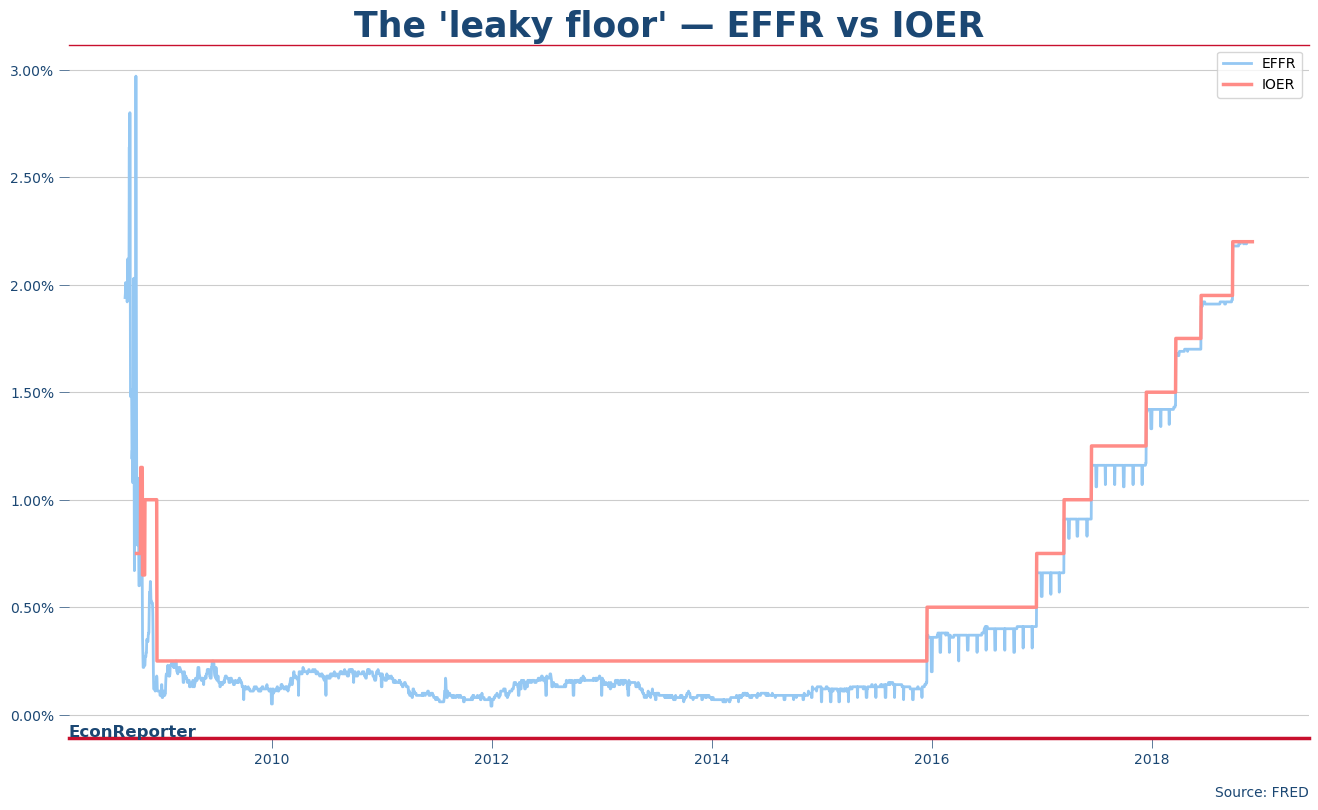

The Fed’s original plan for the (supply-driven) floor system was to use only interest on reserve (IOR) to act as the interest rate floor to keep the money market rates above its lower limit of its target range. However, this plan suffered from a “leaky floor” problem.

As only banks, formally, depository institutions, have master accounts at the Federal Reserve System, hence only they can receive interests generated from their reserve holdings. Other participants in the Federal Funds market, such as Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) and Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs), have no access to the IOR, and this dragged the effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR) below the Fed’s target range, as they are willing to lend out money for interest rate lower than the IOR.

The Fed’s solution is to establish the ON RRP to engage in reverse repo transactions with a wider range of counterparties including not only banks and investment banks, but also money market funds and GSEs such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

“The interest on reserves wasn’t a true hard floor, so we needed this underlying layer called the overnight reverse repo,” Beckworth explained, “I think we need the flip side of that as well. We need access for not just banks, but also for non-banks.”

A potential reason for the Fed’s reluctance is the potential risk associated with financial firms relying too heavily on SRF for liquidity access. “The concern is if you open the standing repo facility to hedge funds and money market funds, then everyone’s going to go there and it’s going to be a big moral hazard (problem). They want to be careful that it isn’t overused,” Beckworth added.

Does the Fed want a demand-driven system though?

In the end, whether Standing Repo Facility will be a central feature of the Fed’s future monetary policy regime still hinges on whether the Fed will adopt a demand-driven system.

Beckworth is not overly optimistic. “No one here seems interested in change. It’s really interesting. Everywhere else in the world, it seems like central bank officials are curious and eager to see if they can improve the systems that they have.”

One major motivation behind the adoption of a demand-driven system in other economies is the desire for a “revival” of overnight interbank lending.

“They want to see banks lending to each other instead of going to the central bank first. They also think this would be a useful market. When banks are lending to each other overnight, often unsecured, they have to know the creditworthiness of the other bank. And so there’s a whole price discovery, a whole market activity that we don’t currently have in the US, and these other countries are trying to resurrect that,” Beckworth argued.

A reason why economies like the Eurozone are more eager to revive active interbank lending is that banking accounts for a much higher portion of that financial activity. “[In the Eurozone], they don’t have as much non-banking financial intermediation. In the US, we’ve got private credit, private equity, hedge funds—we have a lot of other ways that credit gets intermediated through the economy. So, it may be, in some sense, easier for the European Central Bank [to adopt demand-driven system] because banks are the main players in the financial system,” added Beckworth.

Conclusion

So far, the Fed has limited communications with the public on whether it is interested in installing a demand-driven floor system in the US.

The closest one we got is Perli’s speech in May, where he concluded “[n]either approach is inherently superior to the other, and choices around operating frameworks seem to relate to how policymakers weigh competing aims and to jurisdictional differences between financial systems, including the size and complexity of banks and nonbank financial institutions.”

“All we can do is make suggestions and recommendations and hope they end up in a good place,” said Beckworth. “Maybe some other country will try these ideas out before the Fed. The Fed will probably be the last one to do it.”

Independent Economics Journalism

Stay ahead of the curve — follow EconReporter for in-depth coverage on economics & markets.

this report about the SRF is very clear, accurate, and abundant information to help me to understanding why the stablecoin come from. I appreciate with ECON Report.