Wall Street Journal published an article “Financial Markets Face Fresh Wave of Political Uncertainty: There’s Literally Nowhere to Hide” , saying,

“The U.S.-China trade war, Britain leaving the EU and impeachment proceedings in the U.S. are just some of the major political obstacles facing investors. Adding to the uncertainty are the Turkish military operation in Syria, attacks on Saudi oil production and social unrest spanning from Hong Kong to Barcelona.

In response, some investors are boosting holdings of cash and other assets that tend to hold their value when markets turn rocky…”

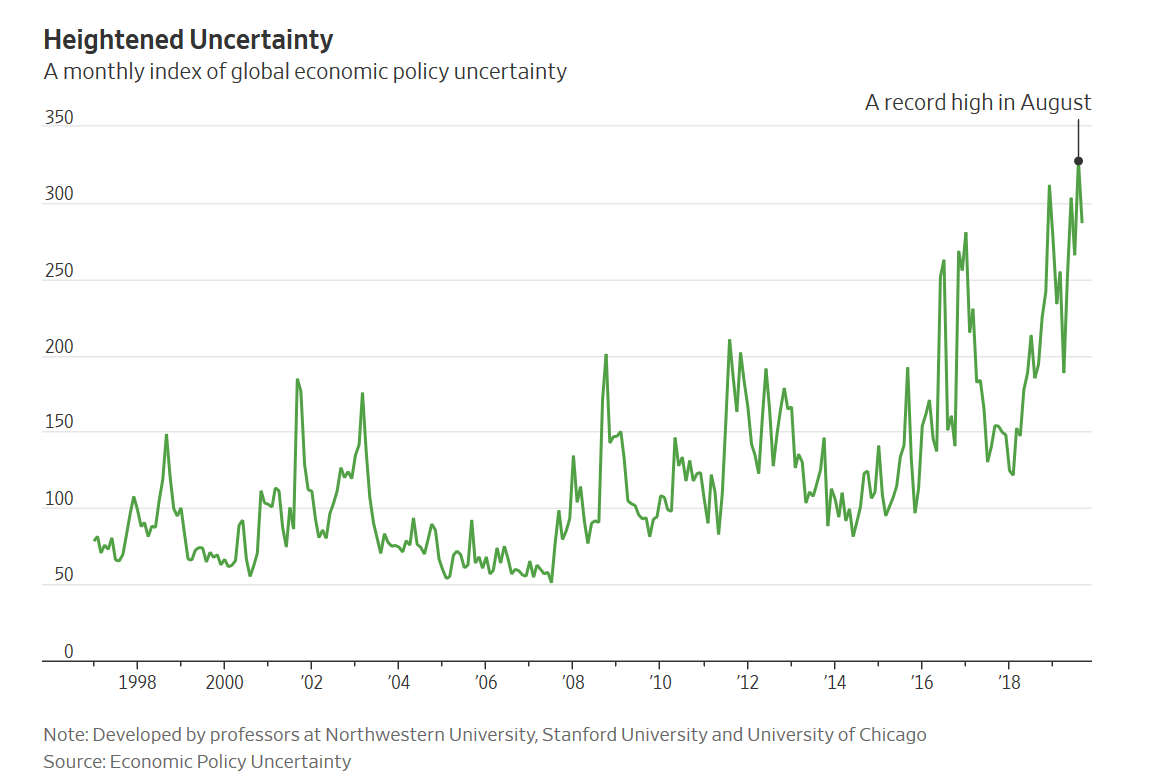

Supporting his argument, writer Steven Russolillo cited the fact that Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (GEPU) is around its record high in recent months.

GEPU is the global version of Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (EPU), an index developed by economists Scott Baker, Nicholas Bloom and Steven Davis. They developed a methodology to scan leading newspapers and calculate the ratio of articles containing the combinations of terms like “uncertainty” or “uncertain”; “economic” or “economy”; and policy terms like “deficit”, “legislation”, “regulation”. The higher the ratio these keywords appear, the higher the economic policy uncertainty.

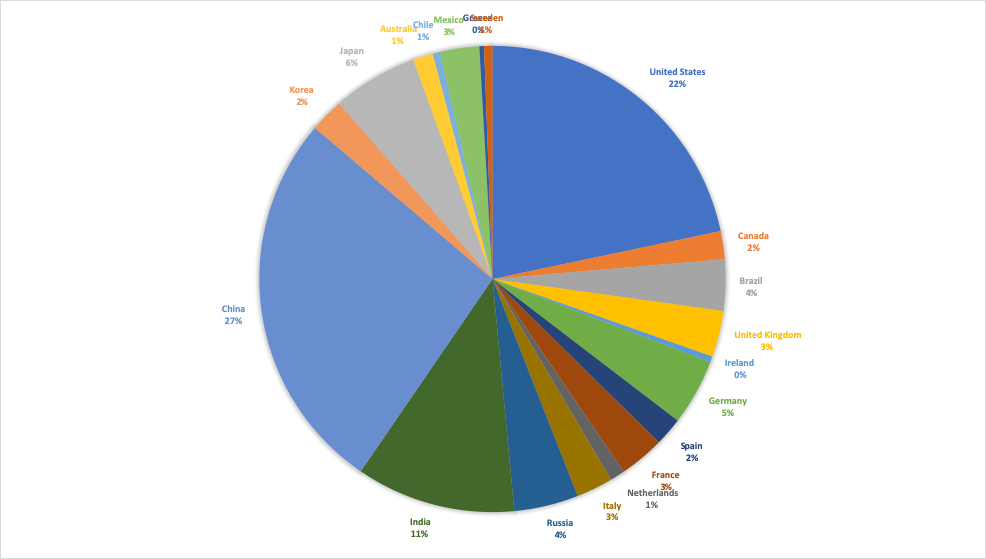

They went on to aggregate the EPUs of 20 major economies, weighted by their GDPs, and computed the GEPU. A general observation is that GEPU usually spikes around major events for the financial markets.

In recent months, the index has risen to a level much higher than periods around the 911 Terrorist Attack or the 2008 Financial Crisis, hence the conclusion that the economic policy is unprecedently uncertain now.

The world is so dangerous, and we should hold cash and invest on safe bets only. Right?

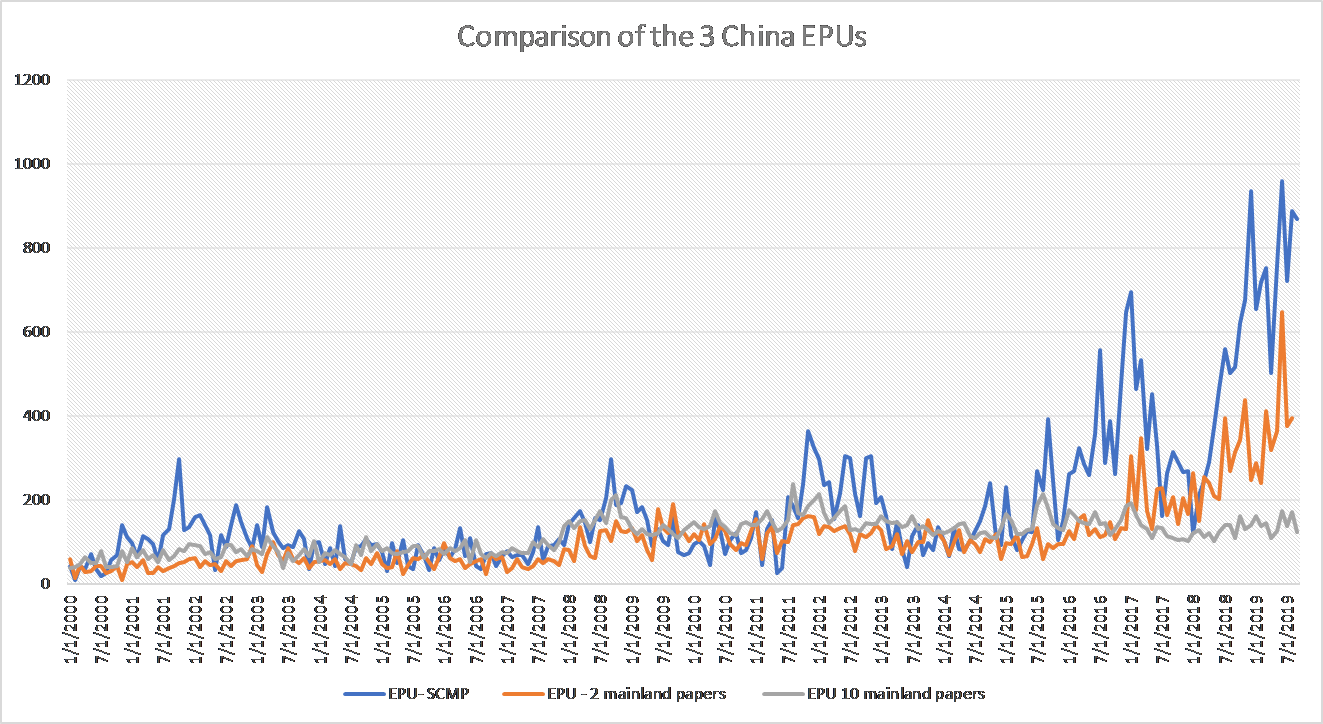

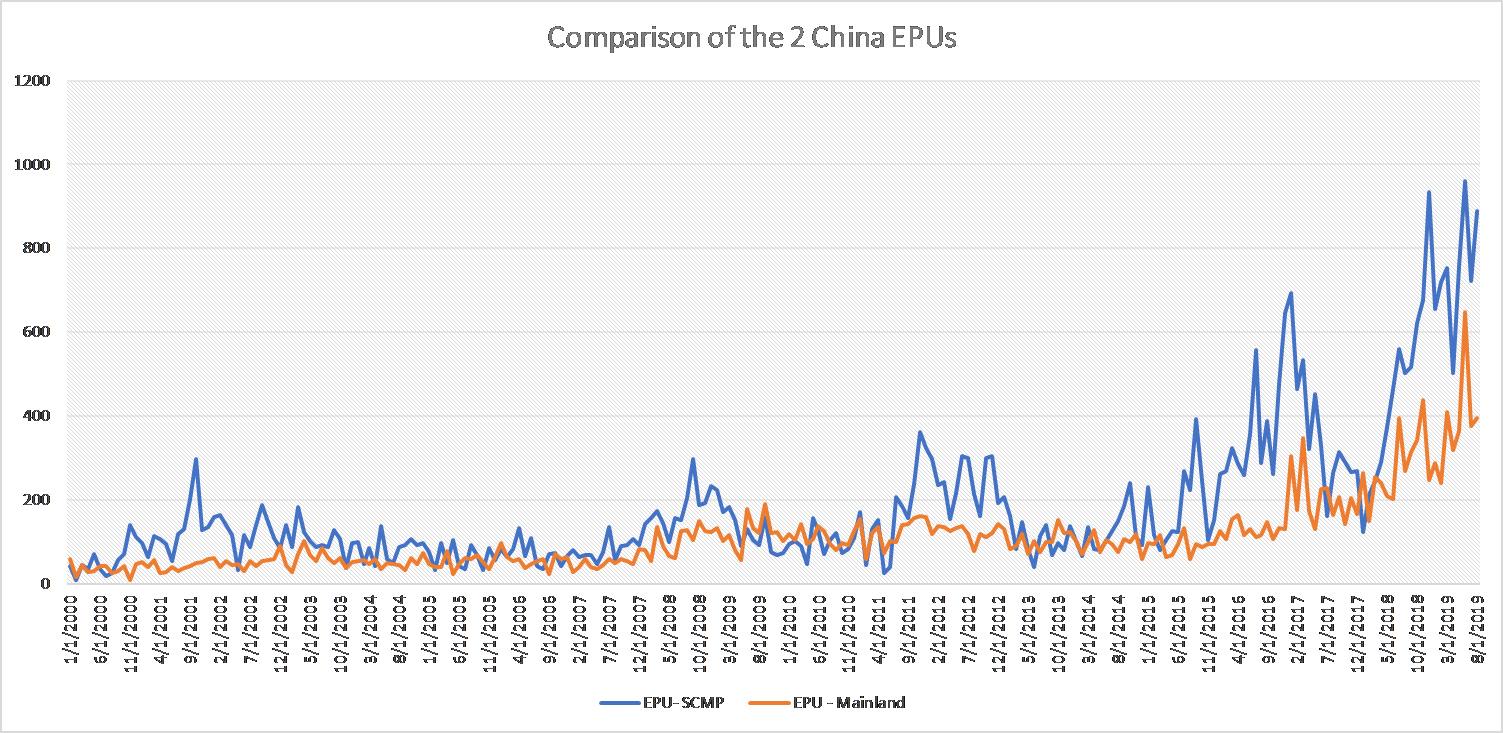

Byron Tsang, associate professor at the Virginia Tech, said a cautious reading of the record level of uncertainty is needed. One issue is that, by weighting the 20 countries’ EPU by their GDP, it gives the China EPU a very high share; however, China EPU is calculated with only one newspaper as it source — the Hong Kong based South China Morning Post (SCMP). For comparison, the US EPU composed of the search results from 10 major newspapers.

It would be possible, then, the unprecedented increase in uncertainty is only a result of changing editorial direction of the SCMP, Tsang wrote in a column published in Hong Kong newspaper AM730.

Based on our calculation with the data from International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook database, the same source three EPU founders used, we see that, as of 2018, China has the largest GDP, in purchasing power parity terms, among the 20 countries included in GEPU. It accounts for around 27% of the total GDP of the group.

It is possible that, if reporters in the SCMP newsroom started to worry about the economy of China, they can significantly impact the readings of GEPU and generate volatility in the index.

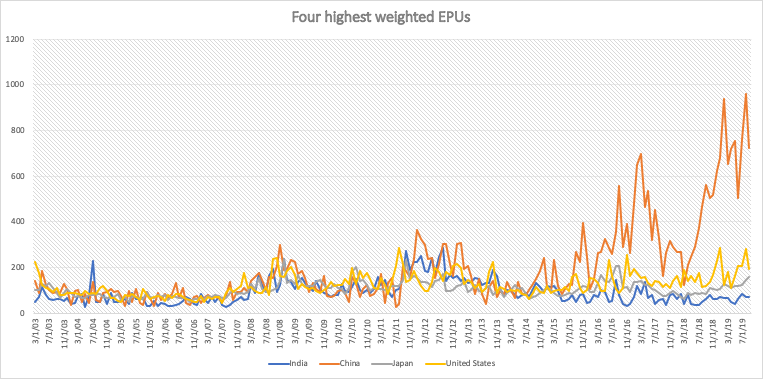

The figure below plotted the EPU of the four highest weighting countries, in total account for 66% of total GDP, and only the SCMP based China EPU experienced a significant increase in recent years.

For this issue, we contacted the three economists who developed the EPUs. They acknowledged this potential issue and offered some suggestion for users of the index.

Steven Davis, professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, said their team have developed another China EPU index and “that China EPU index also shows a very large runup in policy-related economic uncertainty for China in recent years.”

The second China EPU is based on two mainland Chinese newspapers – the Renmin Daily (or People’s Daily) and the Guangming Daily- instead of SCMP. It also shows a rising trend in uncertainty in Chinese economic policies in recent years, as shown below.

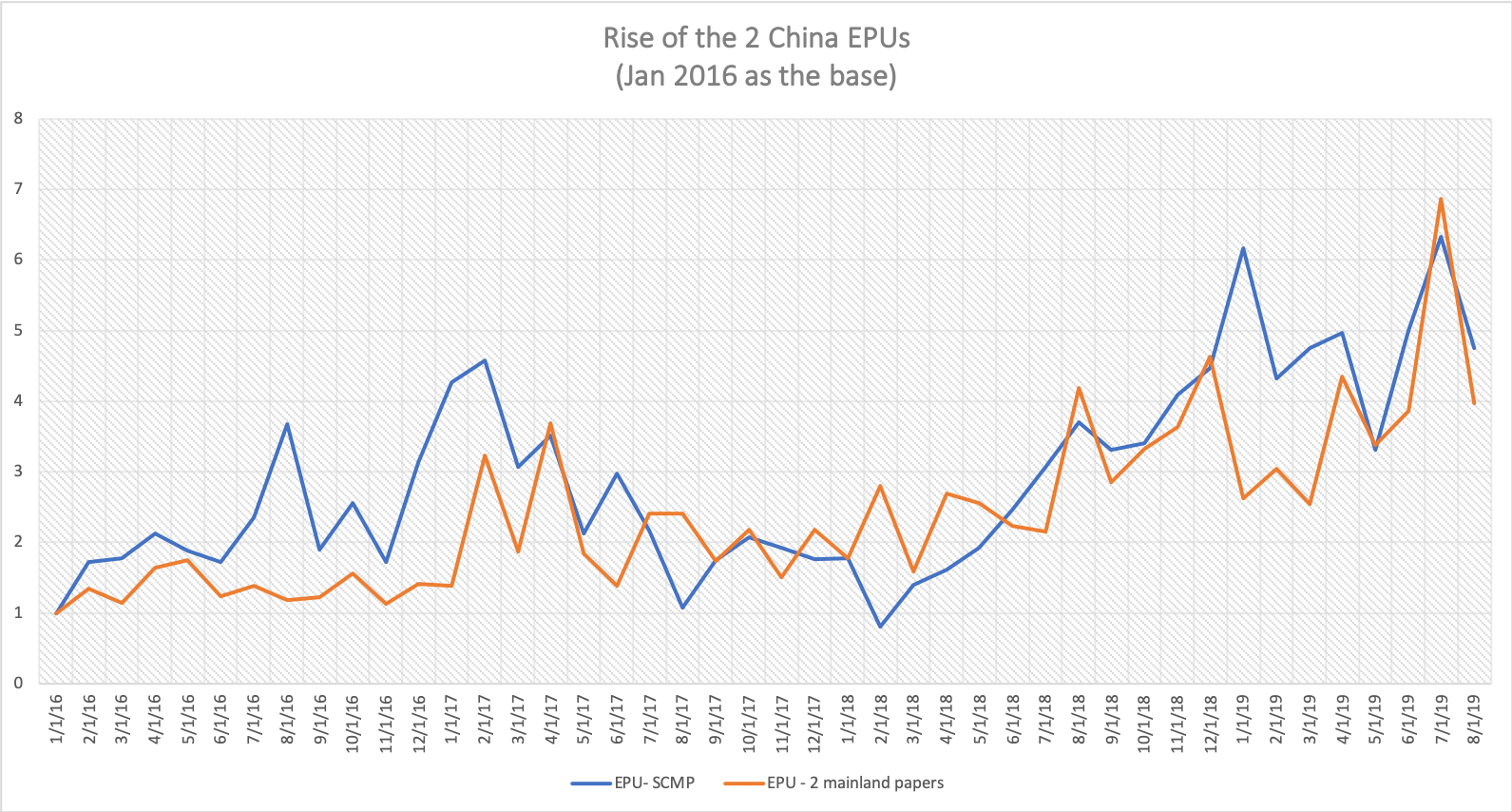

When comparing the relative rise of the two China EPUs, they both increased to four to seven times the Jan 2016 level in recent month.

When comparing the relative rise of the two China EPUs, they both increased to four to seven times the Jan 2016 level in recent month.

“Given that the two China EPU indices draw on quite different sources, and that both show similar increases since, say, 2016 before Trump’s election,” Davis said, “it seems reasonable to infer that the big increase in China EPU is a real phenomenon.”

“Given that the two China EPU indices draw on quite different sources, and that both show similar increases since, say, 2016 before Trump’s election,” Davis said, “it seems reasonable to infer that the big increase in China EPU is a real phenomenon.”

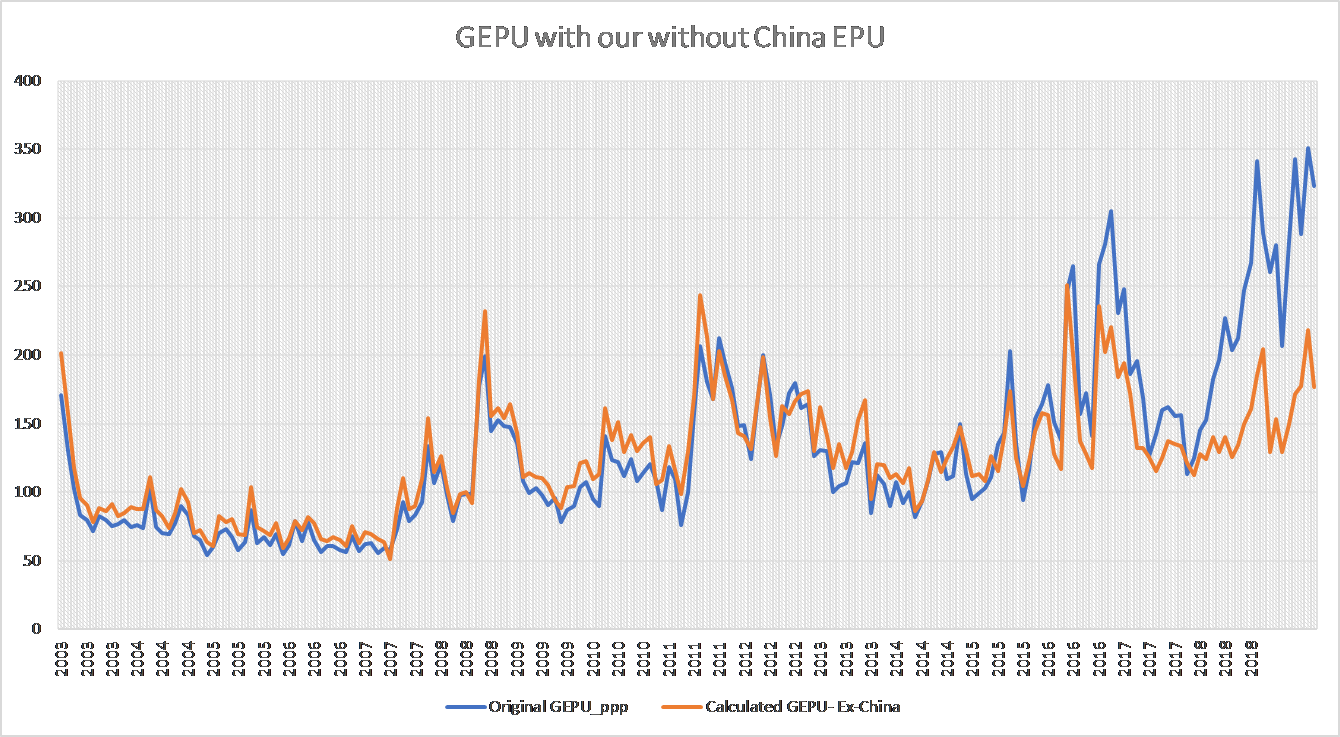

Scott Baker, associate professor at the Kellogg School of Management, suggested that, as all the constituents of their GEPU are publicly available on their website, users of the indices can construct an GEPU ex-China as a benchmark comparison.

We conducted this exercise and tried to compute a GEPU ex-China with only the other 19 countries. The result seems to suggest that the SCMP based China EPU is the major contributor to the recent increase GEPU. Most importantly, the ex-China GEPU is not around its record level now.

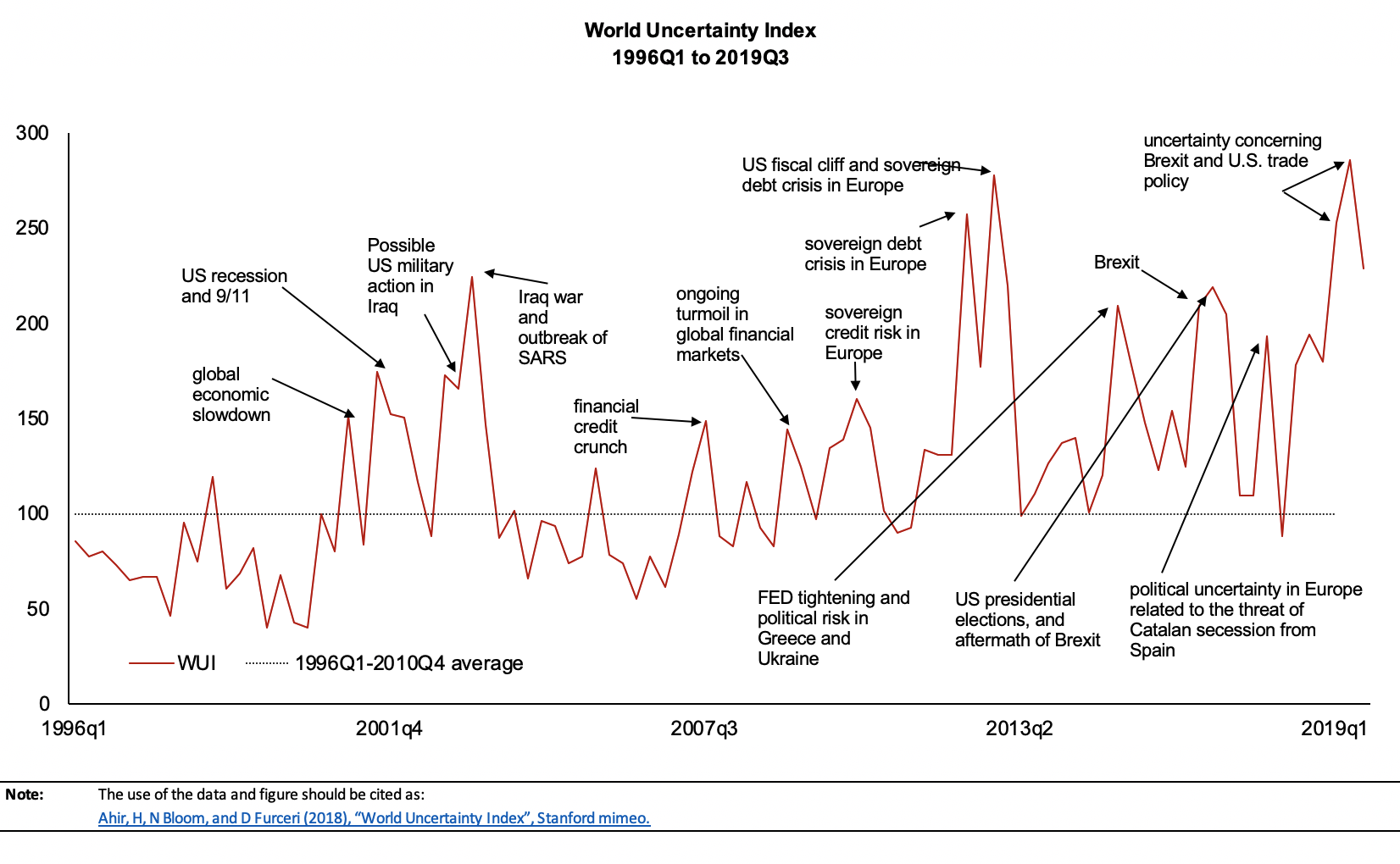

Nicholas Bloom, professor at Standford Graduate School of Business, added their team has another index that can quantitfy the worldwide uncertainty – the World Uncertainty Index (WUI). WUI is calculated using similar method, but the data sources are the quarterly Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) country reports, instead of newspapers.

It can be used as another base of comparison, with the advantage that “the EUI reports are aimed at multinationals and investors who want the unvarnished truth, and the Economist is a neutral outlet,” said Bloom.

WUI is a quarterly data, instead of monthly like the EPUs disscused above, shows the economic uncertainty is rising since Q4 last year, and reached record high in Q2. “This shows a very similar rise and has no problems of being based on domestic newspapers,” Bloom added.

Other economists have also been searching for potential remedies to this issue. Paul Luk and Yun Huang, both from Hong Kong Baptist University, tried to develop an alternative China EPU with more newspaper sources. They picked 10 mainland Chinese newspapers as the source, using the similiar method to compute the index.

Under this version of China EPU, there are no spike in uncertainty in the last few years. Speaking with us, Luk, assistant professor at Baptist University, explained that the observed differences is the result of using different sets of newspapers and different term sets to construct the indices.

“With intensifying trade tensions, it makes sense that EPU in China has increased recently. The real magnitude [of economic policy uncertainty] is probably somewhere between Baker, Bloom and Davis’s index and mine,” Luk added.

Bloom thinks there is a general perceptions that political uncertainty have risen and their index is correct. “This is not the puzzle,” Bloom said, “What is puzzling is why financial markets are so calm and economic growth so flat. But maybe that is about to change – I hope not, but it makes me worried that the EPU is a leading indicator of a big crash.”

(The article is updated to reflect further discussions with Nicholas Bloom and Steven Davis after it is published. A paragraph and figure clarifying the relavtive increase in the two China EPUs, and discussions about WUI and a graph showcasing the index was added. The comments from Bloom at the end of the article was also drawn from discussions after the article published.)

>>> You can follow EconReporter via Bluesky or Google News