Last Updated:

It’s been 10 years since the 2008 financial crisis, and with the financial market making new records week in week out, people are wondering about when the next crisis will come. And, more importantly, when the next crisis hit, do we have the tools to deal with it?

Central banks and many economists are confident that Quantitative Easing (QE) can be a reliable crisis-fighting tool. However, according to a recent research, the confidence in QE might have been a misguided one, as previous studies may have overstated the effectiveness of it.

In their working paper “A Skeptical View of the Impact of the Fed’s Balance Sheet,” economists David Greenlaw, James D. Hamilton, Ethan Harris, and Kenneth D. West challenge some earlier studies that concluded QEs have a significant economic impact. The major issue is that when those research used simple event studies to quantify the impact of QE, the result might be biased.

Why might event study not be an excellent way to study the input of the QEs?

Economists often use market reactions in the treasury yields shortly before the announcements of QEs, or other related events, to quantify the ‘impact’ of the asset purchases programs. But according to Greenlaw et al., this event study method might suffer selection bias, as economists only focus on the days with dramatic market movements.

Instead of focusing on some short time periods, they suggest a complementary observation technique: the authors are the Reuters News to double check the result of previous research results based on event studies. They record all the days that the 10-year US treasury yield had movement larger than one standard deviation, then the check the Reuters News report that day to identify the “source” of market movements. If the Reuters identified the Fed’s action or speech is the major reason for the market movement, it is marked as “Reuter Fed Day”. Then they added up all the market movement on “Reuters Fed Days” during the period of QE 1, QE 2, and QE 3, and use it to “measure” the impact of the Fed’s unconventional monetary policies.

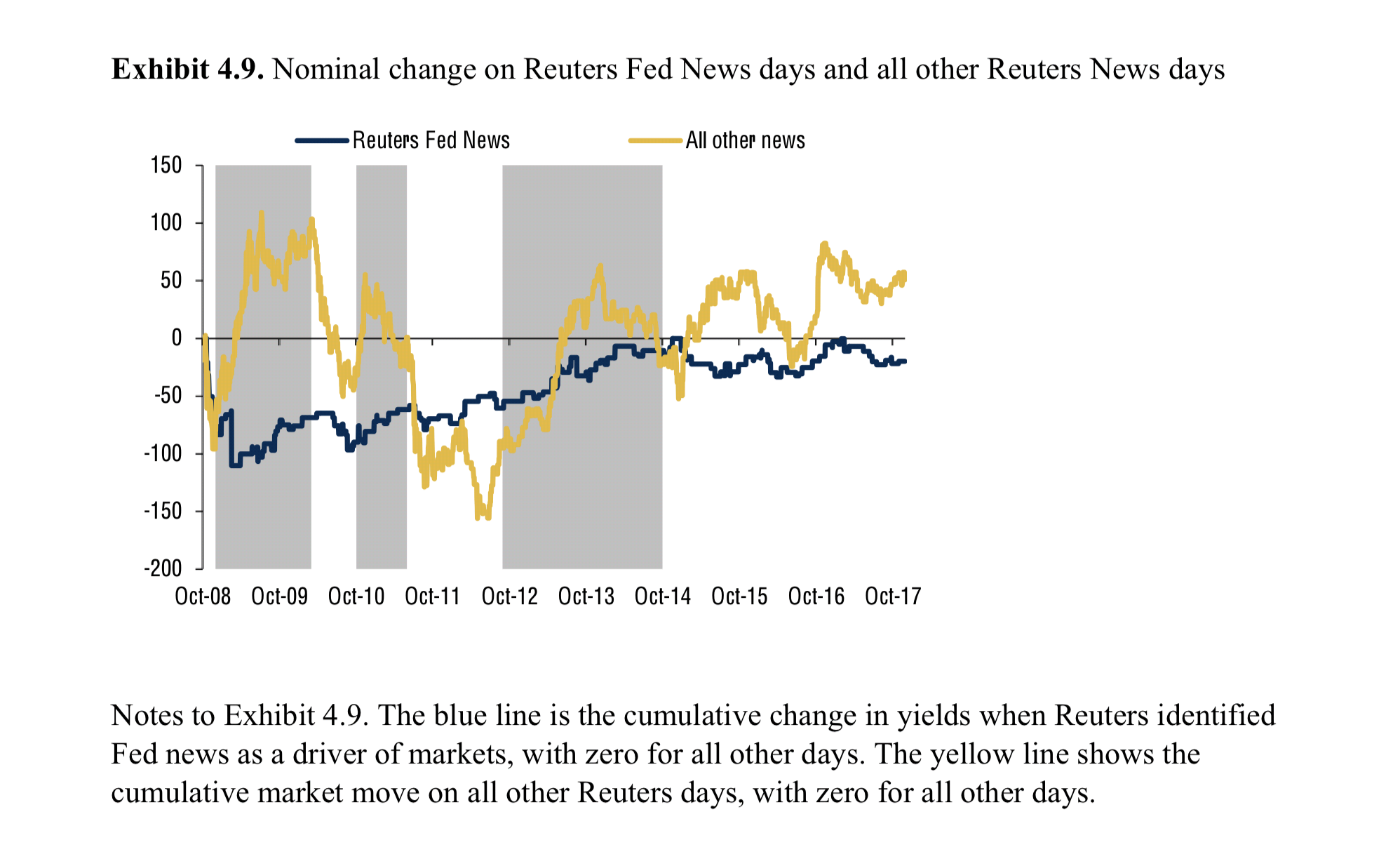

Here is the summary of all the 10-year treasury yield reactions at the ‘Reuters Fed Days'(dark blue line).

The result shows that 10-year treasury yield is cumulatively lower in all ‘Reuters Fed Days’ during the period, as one would expect from a monetary easing policy.

However, most of the fall in yield concentrated in the period before QE 1; During QE 2 and QE 3, the cumulative fall in l0-year yield actually got smaller, which means that the yield is trending higher even with all the Fed actions. This put in doubt the effectiveness of the event study method, as economists will miss out all the subsequent market movements that might be related to the QE. In this particular case, the “effect” of QEs might have faded away very soon after it is implemented.

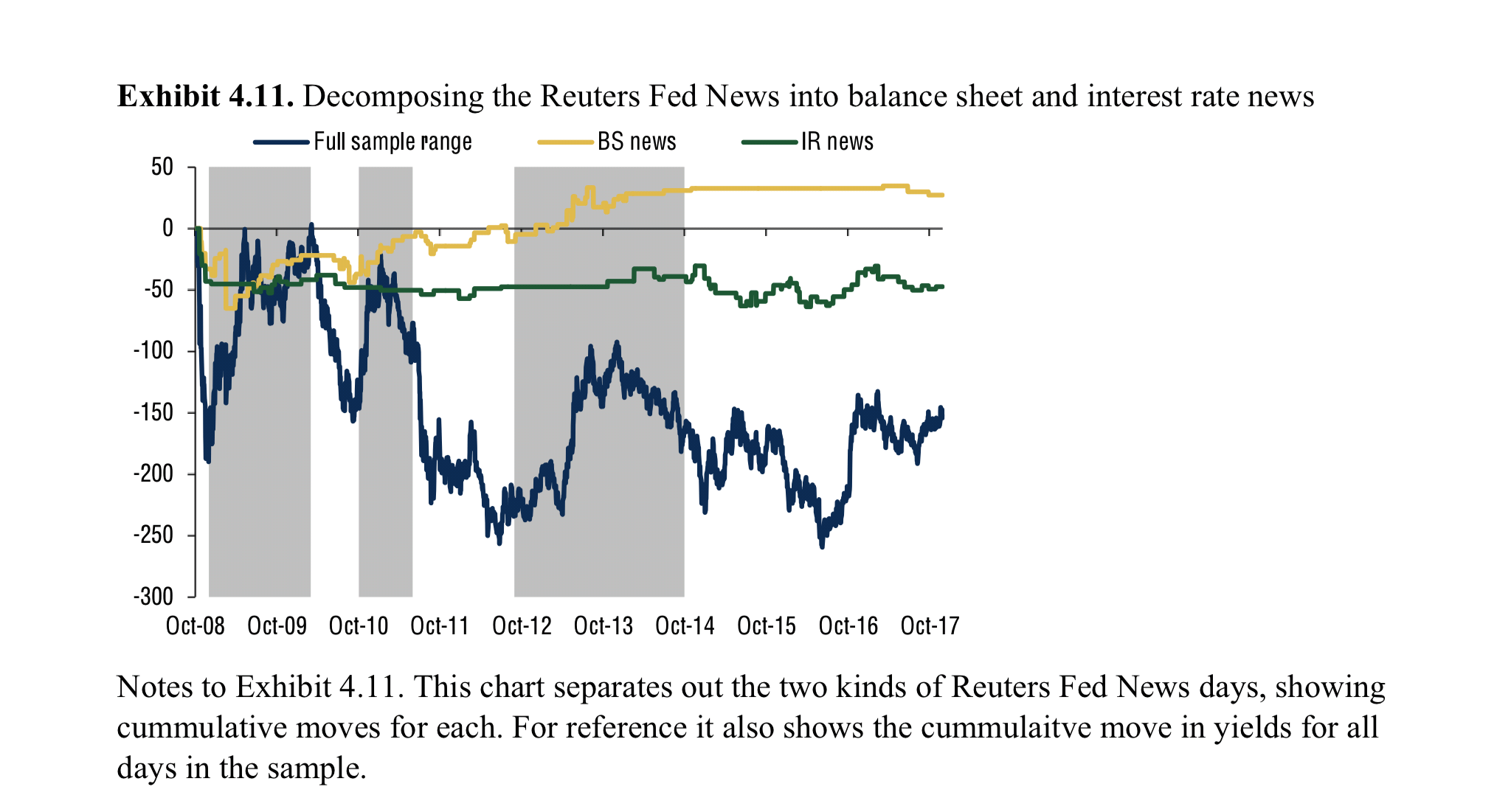

The research also distinguished the reason for yield changes on “Reuters Fed Days’” between “balance sheet news-related” and “interest rate news-related”.

One the one hand, the yield change related to interest rate remains negative and stable during the period; one the other hand, the cumulative yield change on days dominated by news about the Fed’s balance sheet fell before QE1, but the yield is trending upward since then and turned positive before QE3. Again, this is not a picture one should expect as QE should lower the 10-year yield instead. This is why the authors make a bold claim that that interest rate policy is a better way to ease monetary policy, as compared to asset purchase programs as the effect is well known and stable.

But please keep in mind that the authors’ claim is still hotly debated.

As one of the authors of those original event studies, Joseph Gagnon of PIIE argued that Greenlaw et al. might have overstated their case. Gagnon argues that to use an event study method to measures the effect of a policy on an economic variable, including the “alternative” method Greenlaw et al. used, certain critical assumptions of event studies are needed: “(1) the policy in question was not expected prior to the news events, (2) the news events are the only times the market changed its expectations about the policy, (3) those expectation changes occurred entirely within the event windows, and (4) nothing else happened during the event windows to affect the economic variable of interest.”

These assumptions are clearly violated in programs other than QE 1, hence those results might not be really indicative. As for the measured economic impact of QE 1, Gagnon argues that Greenlaw et al.’s result is actually in line with the one he gets in a 2011 paper he coauthored.

Still, “A Skeptical View of the Impact of the Fed’s Balance Sheet” provide some insightful study on asset purchase program by central banks and readers interested in monetary policies and central banking should read it. Just keep in mind the debate is a lively one and the dust far from settled.

[Traditional Chinese version of the article can be found here.]

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡