Last Updated:

A revolutionary money and banking reform may happen next week in Switzerland.

The Swiss sovereign-money referendum, also known as the Sovereign-Money Initiative, which aims to creates a safe and crisis-free, yet experimental banking system in Switzerland, will be held on 10th June. The initiative proposed the creation of a banking system which all demand deposits in the country will be held by the Swiss Central Bank, and all the loans are totally backed by central bank issued money, the so- called “Sovereign Money.”

According to the Sovereign Money Initiative, a major problem in the modern banking system is that privately-owned banks, instead of just central banks, have the power to “create money.” By taking a deposit from customers and using a significant fraction of it to make loans, the banks are in essence “printing” new money that has no physical form but exists on the balance sheet of the banks. The Initiative argues that the privately-created money is one of the major issues of the modern financial market which exemplified in the 2008 global financial crisis.

To cure this problem, we should give all the money printing power back to the central banks, the initiative claimed; and the bank should no longer be allowed create money in any form. Not in the form of coins and bills, neither should they be allowed to create e-money that exists in the accounting book.

How can we achieve this ambitious goal? Replace all the privately created money with sovereign money.

In simplified terms, after the implementation of the sovereign money regime, when a bank receives demand deposits from the customers, instead of holding it on their balance sheet, the bank pass the deposit along to the central bank. In return, the central bank will create new sovereign money and hand it to the bank. Now, the liability (in the accounting sense) of the bank is no longer the deposit it received, but the sovereign money it got from the central bank. The bank can then freely use the sovereign money it has on hand for any lending activities.

What is the point of this “revolutionary” arrangement?

For starter, because all the demand deposits are now transformed into sovereign money, that means they are 100% backed by a central bank issued asset. So, when the banks collapse, the depositor can rest assured that they can get back all the sovereign money in their account.

More importantly, as all the demand deposits are now 100% backed by central bank assets, the multiple equilibria bank-run problem traditionally inherited from the fractional reserve system is no longer an issue.

Remember what you have learned from your high school economics textbook, under fractional reserve banking system the banks take deposits from the customers and will keep a portion of the money, say 10%, as a reserve to fulfill the requirement of the central banks. After keeping the 10% reserve, the bank would then lend out the 90% left in its book. As any elementary textbook would tell you, the banking system can create 10 times (1/10%) more “money” with this mechanism; or as economists would put it, this banking system has a money multiplier of 10.

The problem with the above-discussed fractional reserve system is that 9 out of 10 dollars of the money recorded in the banking system is, if you will, “created out of thin air.” If depositors collectively withdrew more than 10% of the deposits from the system all at once, the system will not be able to satisfy such demand, and it will collapse. Moreover, the mere fear of bank run will soon happen could “encourage” depositors to withdraw money from the banks, and push the system towards the cliff in a self-fulfilling way. This is the bank-run problem of a fractional reserve banking system, and why such system is regarded as “inherently unstable.”

This is the basic argument of the Sovereign-Money Initiative. Just use central bank-issued sovereign money to replace all privately created money, and get rid of the fractional reserve banking system. Then, we will have a bank-run free and much safer financial system.

Or, so they argued?

Philippe Bacchetta, Swiss Finance Institute professor of macroeconomics at the University of Lausanne, has written a detailed analysis on the macroeconomic effect of the sovereign money initiative. The conclusion is that the overall impact of such reform can be negative.

The reason is that the sovereign money reform may not be able to prevent several main culprits of modern-day financial crises. An important point to keep in mind is that modern banking crises are not caused by runs in deposits, at least according to recent economics research.

As exemplified by the widely-cited research of financial economist Gary Gorton, runs in commercial paper and money market is what really caused the financial crisis in 2008. And recent research by Òscar Jordà, Björn Richter, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor went on to argues that it is the non-deposit bank liability, rather than deposits, that tend to predict banking crises in the recent history.

In an interview, Bacchetta explains that “by guaranteeing demand deposits at the central bank, sovereign money would avoid a run on these deposits. [But] since recent crises are not related to these deposits, a sovereign money system would make no difference,”

A sovereign money regime, though effectively require 100% reserve on demand deposits, is not going to prevent a sudden withdrawal of funds from the money market, is not going to be very helpful in reducing the probabilities of future crises. “Even in the case of British bank Northern Rock in 2007, the run came from other financial institutions, i.e., from short-run liabilities that are not included in M1,” Bacchetta explained in his research.

Swiss National Bank, the central bank of Switzerland, has put forth a similar point in their official arguments against the sovereign money reform. SNB said that the principal causes of the recent financial crisis are “the belief that asset prices can go on rising indefinitely, complex financial instruments with opaque risk liability, the accumulation of excessive amounts of short-term debt via the money and interbank markets, and instability at investment banks with no deposit business.” These factors can’t be circumvented under the sovereign money system, the central bank argues.

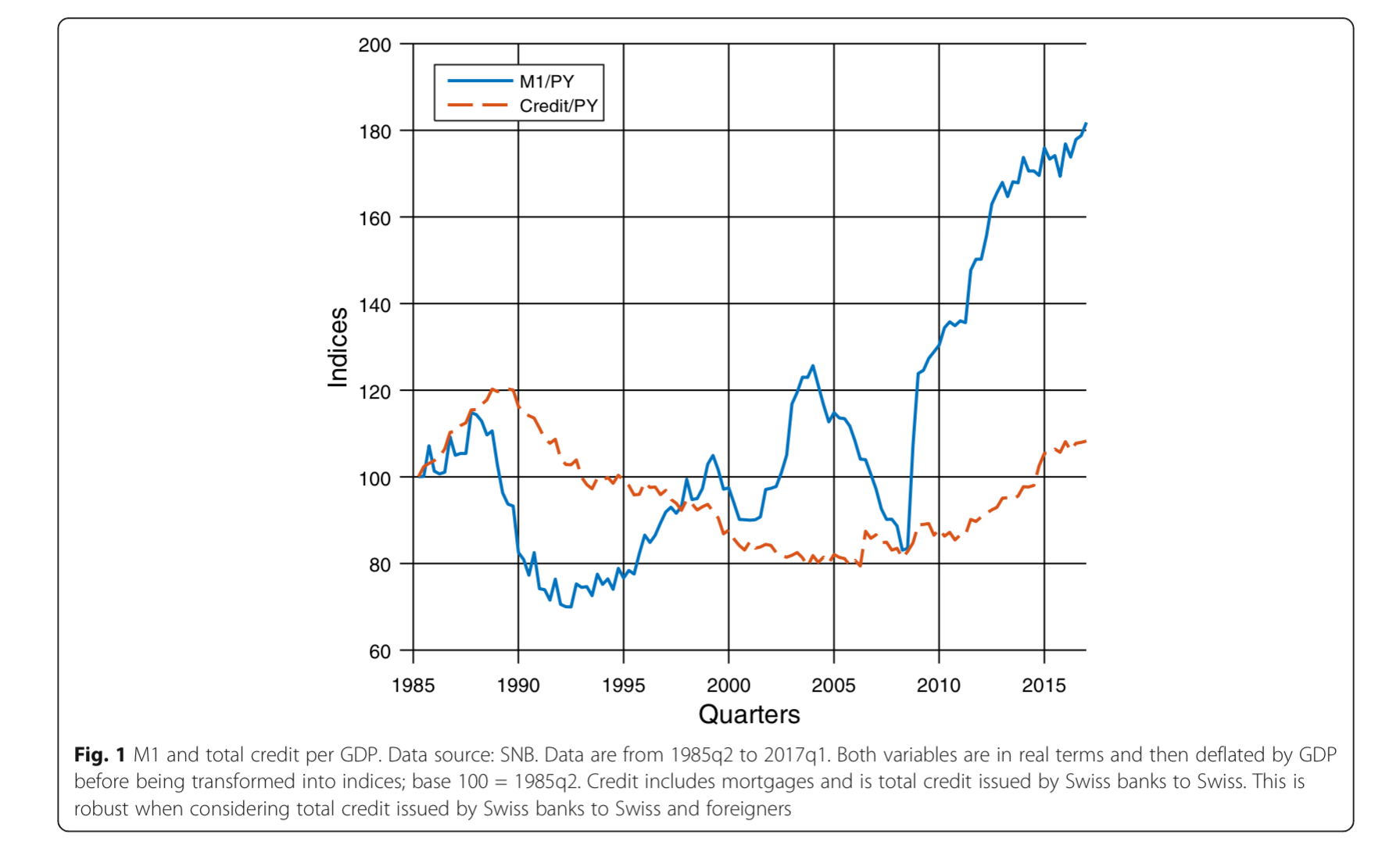

Another important point is that the growth in credit is not correlated with the growth in money, defined as M1, which is made of banknotes and demand deposits at commercial banks. That means, even if the Sovereign Money reform makes demand deposits under the control SNB, it may not be able to curb any future excessive credit growth after all. “These [demand] deposits are liabilities for banks, while credit is an asset. However, demand deposits in Swiss francs represent less than 20% of banks liabilities in Switzerland and credit is only one part of the assets. So, there is no strong link between money and credit. This is especially true before financial crises where credit increases, while money tends to decrease,” said Bacchetta.

The above figure provided by Prof. Bacchetta illustrates the point. The blue line is the ratio of M1 to the nominal GDP of Switzerland, the red line is the ratio of credit to nominal GDP. As you can see, between 2000 and 2008 there is a sharp rise in the M1 to GDP ratio, yet the credit to GDP ratio remained stable. And after the 2008 financial crisis, the M1 ratio almost doubled, but the credit ratio only rises about 25% in the next several years.

Scott Sumner, Director of the Program on Monetary Policy at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and popular blogger at The Money Illusion, also thinks the Sovereign Money Initiative is not a perfect solution to eliminate financial risks in the banking system. He wrote in a blog post back in February, raised a similar point as Bacchettta. “Even under this proposed regime, the 100% reserve requirement would only apply to demand deposits. Banks could still lend out funds in saving deposits, and hence the same risks to the system would still exist.”

Sumner further explained in a recent interview with us, “I do not support a 100% reserve system, as there are better ways to achieve the goal of making banking safer.” One of the problems with modern banking system is that numerous regulations create moral hazard in the financial sector.

“In my preferred system, there are two components. First, remove all moral hazard from banking, by not providing any sort of government insurance for banks or depositors.” The government insurance he mentioned includes deposit insurance and too-big-to-fail bailouts. These are well-known examples of implicit subsidies that create incentives for banks around the world to pursuit risky excessive lending.

Though Sumner conceded that “a true 100% reserve system could remove risk from the banking system, making a banking crisis less likely,” the fact that the sovereign money regime only cover demand deposits makes it an incomplete 100% reserve system. And without fixing the incentives the banks faced, financial instability would still be a risk facing the Swiss even if the Sovereign Money Initiative is implemented.

Instead of sovereign money, Sumner suggested another “revolutionary” monetary reform that the Swiss should consider. Yes, you guessed it. “Do NGDP level targeting.”

Sumner has been advocating the Federal Reserve to adopt NGDP targeting for years, he thinks the same reasoning can apply to Switzerland also. “Stable NGDP reduces financial instability because it is NGDP, not RGDP, that determines the ability of people, businesses, and governments to repay their debts.”

According to Sumner’s research , there is evidences that sharp fall in NGDP causes financial crises. If the central bank can maintain stable growth in nominal income of the people, it might reduce the occurrence of financial instability. Even if a financial crisis happens, given that the nominal income of people is still stable, it can greatly reduce the negative impact of the crisis.

“Yes, Switzerland can target NGDP even with a small open economy,” Sumner said.

We should note that the Sovereign Money Initiative haven’t claimed that the proposed reform can be a once-and-for-all cure for all the financial trouble that Switzerland would ever face.

In a rebuttal to SNB’s criticism, they wrote that “it is not the aim of the Sovereign Money Initiative to solve financial stability problems. However, the aim is that should there be a financial crisis, money in current accounts would be completely safe. Thus normal transactions in the economy would not be jeopardized.”

In another paragraph, they again admitted that financial crises can still happen under the sovereign money system. “If this were to happen, the SNB would struggle in its task of facilitating and securing the functioning of the cashless payment systems. The sovereign money system will ensure that transactions can continue even during a financial crisis. The dependencies of the society on a well functioning financial system will be much reduced in a Sovereign money system.” So, their more specific claim is that the proposed system can reduce the negative impact of a financial crisis, should it happen again.

Also, they claim that sovereign money regime can help reduce the problem of too-big-to-fail problem. “If banks make poor decisions when granting credit and get into solvency problems, they can go bankrupt like any other business (but sovereign money accounts would be completely safe)… [Moreover,] banks can fail without any direct consequences such as a standstill of the payment system of the whole country.”

Unfortunately (or fortunately if you are a Swiss who oppose the initiative), the poll is showing that more than half of the Swiss are not supportive of this proposed reform. A recent poll run for the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation showed 54 percent of people were either strongly against or against the sovereign money initiative, up from 49 percent in early May. Only 34 percent of people either strongly supported or supported the initiative.

Hence, unless the poll is as off as those predicted Donald Trump won’t be winning the election, it is more like than not we won’t know whether the sovereign money system can help Switzerland to reduce financial risk of any kind.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡