Last Updated:

Quantitative tightening (QT)—a process central banks use to reverse years of liquidity creation from quantitative easing (QE)—is concluding in many advanced economies. The central banks are growing confident that reserve levels in their financial systems are nearing their endpoints.

In the US, the Federal Reserve defines the QT endpoint as an “ample reserve level“; in the Eurozone and the UK, the goal is to covert their interest rate regimes to a so-called demand-driven floor system.

The underlying ideas are more or less the same: central banks aim to reduce excess liquidity to a point where the reserve demand curves begin to slope upward.

However, the different naming of their frameworks reveal subtle transatlantic differences in QT endgames.

But first, let’s cover the basics of the post-QE interest-rate-setting system.

Explainer on the post-QE reserve demand and supply

One major effect of QE is that it changed how central banks conduct their interest rate policy.

Take US as an example: before QE the Fed adopted a scarce reserve system.

- The central bank had to adjust daily the level of reserves in the banking system to match shifts in reserve demand and maintain fed funds rate at its target.

- This setup is also called corridor system, with interest on excess reserves as the floor and discount rate as the ceiling. The fed funds rate could fluctuate within this range, requiring the Fed to adjust reserve supply to guide the overnight rate toward its policy target.

QE—through which the Fed bought long-term Treasuries and other securities like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) with newly created reserves—flooded the banking system with a never before seen amount of reserve supply. This pushed the fed funds rate down to the floor of the interest rate corridor.

This is when the Fed shifted to the so-called floor system, or more officially an “abundant” reserve system. Its primary interest rate control tool became the interest on excess reserves (later redefined as interest on reserve balance, IORB, as all reserve became interest-bearing).

- Because the excessive level of reserves pinned the fed funds rate to a level close to IORB, the Fed can then guide the overnight interest rate by ratcheting IOBR up and down.

Since not all money market participants have access to the fed funds market, overnight rates in money market and fed funds rate tends to fall below the IORB.

- The Fed, therefore, employed overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP) as a complementary tool to ensure fed funds rate stays close to its policy target.

- Money market funds can deposit their liquidity into ON RRP. Since these funds then have the option of receiving ON RRP rate or lending the money out to other counterparties to earn prevailing money market rate, arbitrage tends to align the two rates, making the ON RRP a supplementary floor for the fed funds rate.

What is ‘ample’?

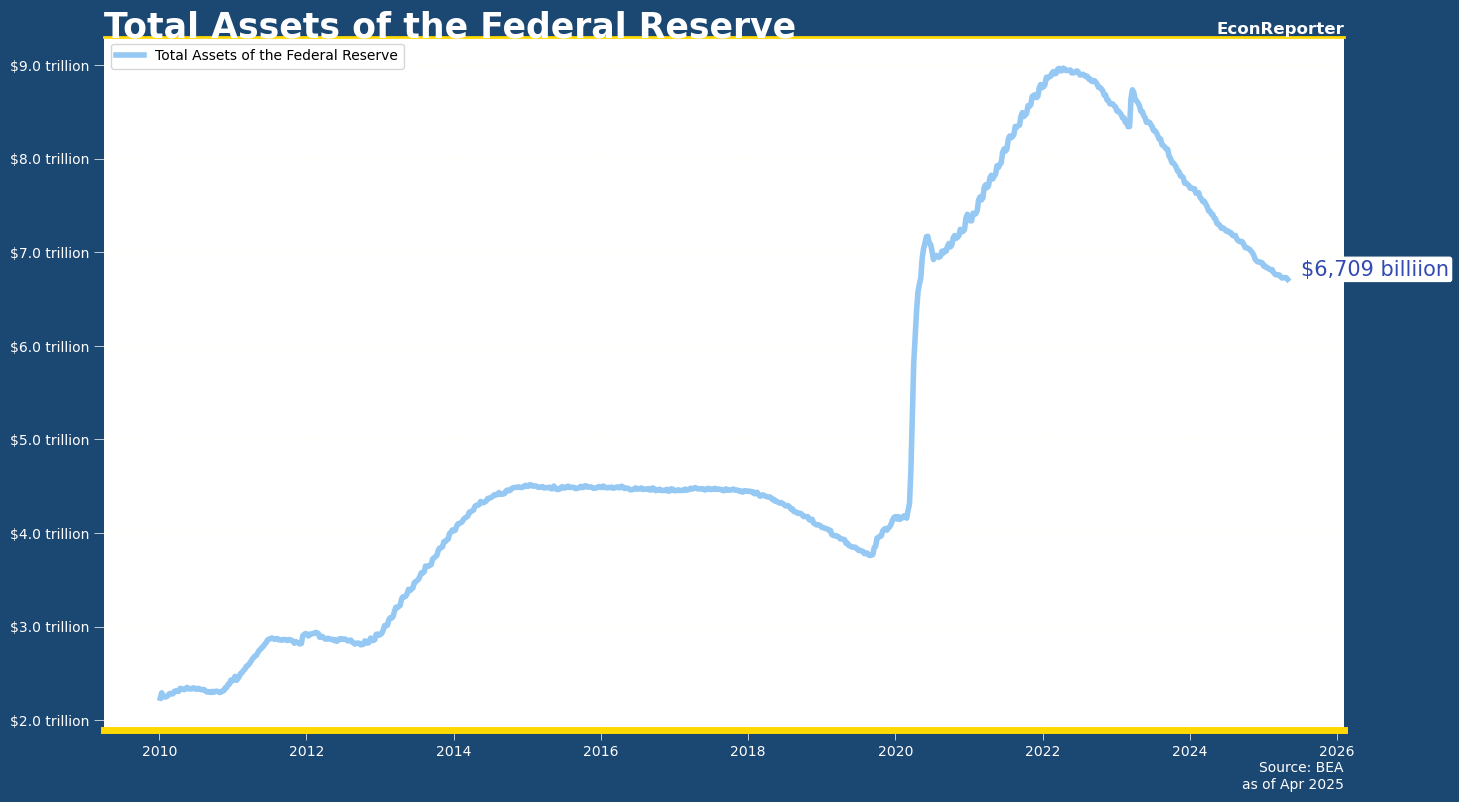

The Fed restarted QE in the Covid period, boosting its balance sheet size close to USD 9 trillion by early 2022.

To normalize the size of its balance sheet, the FOMC agreed in June 2022 to begin QT by allowing a certain amount of its Treasury and MBS holdings to mature. The aim is to bring reserve levels to a so-called “ample reserve” level.

So, what does “ample” mean?

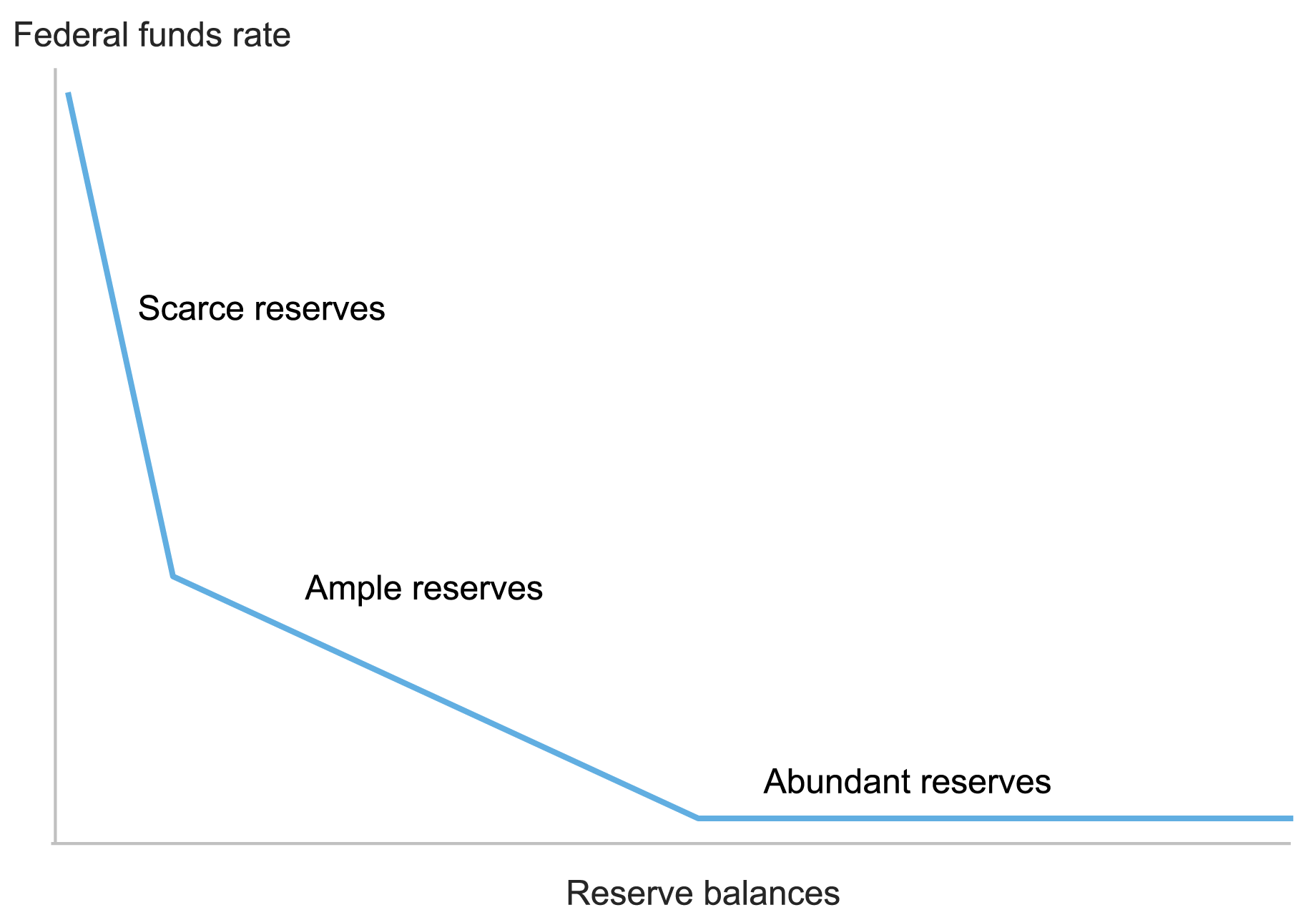

It’s best explained using a reserve demand graph from the New York Fed. According to the regional Fed’s characterization, ample reserves is a special zone where further contraction of reserve supply begins to raise fed funds rate, but not significantly.

- This is described as the minimum amount of available reserve required to keep floor system operational without needing daily tweaks to reserve supply to match changes in reserve demand, as was common in the scarce-reserve era.

The NY Fed has developed a tool called Reserve Demand Elasticity (RDE) to measure how sensitive fed funds rate is to reductions in reserves. If RDE estimate turns negative and is significantly different from zero, it indicates that reserve demand is leaving the “abundant” region and moving into the “ample” level.

European calls it ‘demand-driven floor system’

In the Eurozone and the UK, the QT endpoint isn’t called an “ample” level of reserves. Instead, they use the framing “demand-driven floor system.” What does this mean, and how does it differ?

The basic objective is the same: to reduce the amount of reserves in their financial systems to a level very close to the minimum needed to keep the floor system operational. So, what does demand-driven versus supply-driven mean in this context?

Under this categorization, years of QE created an excessive supply of reserves, where the central bank-determined level of reserve supply was the dominant force keeping the floor system functional.

A demand-driven system attempts to give market demand for reserves a more prominent role in the regime. In such a system, the banking system determines the level of reserves it needs, and the central banks will match this demand.

How does this work? In the UK, the Bank of England (BoE) relies on its Short-Term Repo (STR), which allows banks to borrow reserves for one week with high-quality collateral. The interest rate the BoE charges is set at the same level as the Bank Rate, its policy rate. (Also, the British central bank named the “ample” reserve region “Preferred Minimum Range of Reserves,” or PMRR.)

As reserve level in the financial system drops to a level close to “scarce”, bank can access STR to acquire reserves they can’t obtain from the money market to fulfil their liquidity needs. This way, banks’ demand for liquidity can create matching temporary reserve supply through the STR, effectively placing control of the overall reserve level with market demand—hence, a “demand-driven floor system.”

European Central Bank (ECB) has a similar setup. The facility tasked with providing short-term liquidity to match reserve demand fluctuations is its long-standing main refinancing operations (MROs).

The MRO rate, one of three policy rates set by the ECB, was considered the central bank’s primary policy rate benchmark before the currency bloc engaged in QEs. The MRO allows banks to borrow as much liquidity as they demand for a one-week period at a fixed rate by providing ECB qualified collaterals. This will be an important tool to ensure demand-driven floor system is operational.

Both the BoE and ECB are also developing longer-term lending facilities for banks to signal their demand for extra liquidity as well as to acquire those liquidity at a more predictable and stable manner.

Fed’s Standing Repo Facility

In fact, the Fed has a similar tool: Standing Repo Facility (SRF). Operated by the New York Fed, it lends reserves overnight to eligible banks in exchange for collateral. The minimum interest rate for SRF is set at the upper bound of the Fed’s interest rate target range. In theory this could help cap sudden surge in short term money market rates as well as effective fed funds rate.

The SRF, like the STR in the UK and the MRO in Eurozone, can provide short term liquidity in response to fluctuation in demand. Thus, in essence, the Fed also has developed the fundamental for a “demand-driven floor system”.

While the Fed is not currently communicating this explicitly, it is hinting in this direction. The minutes of March 2025 FOMC meeting stated that “a number of participants” thought existing tools could address potential disruptions in the reserve market. “Some participants” welcomed the NY Fed’s continued efforts to improve the efficacy of the SRF as part of the central bank’s interest rate ceiling tools.

Notably, Governor Chris Waller voted against slowing the pace of QT, saying the Fed “should rely on its existing tools and develop a plan for how to respond to short-run strains if they emerge.”

It’s increasingly apparent that the Fed will have to decide whether it intends to explicitly adopt some sort of demand-driven floor system and which tools would maintain it. Discussions are ongoing and seemingly in the early stage. With the pace of Treasury redemption slowed to USD 5 billion a month, however, the Fed is likely not in a hurry make a final decision.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡