Last Updated:

Analysts are expecting the Federal Reserve to announce the end of quantitative tightening (QT) at the upcoming meeting this week. The speculation is fueled by Chairman Jerome Powell’s speech earlier this month in which he mentioned the supply of reserves may reach an “ample” level “in coming months.”

Discussions about the end of QT is also supported by the fact that market interest rates in the money market have shifted up in recent months.

SOFR generally settles in the lower half of the US central bank’s Fed funds rate target range. But in the last two months, it has shifted to the upper half. This is interpreted by some commentators as a sign that QT has drained enough liquidity from the system and that by continuing the squeeze, the Fed may risk losing control of its interest rates like it did in September 2019.

While those are reasonable concerns, it’s vital to remember that the Fed has set up a new set of ceiling tools after 2019. The Standing Repo Facility (SRF), which allows banks to obtain overnight liquidity with high-quality collateral like Treasuries through a repurchase agreement, is the most obvious example.

Such ceiling tools are designed as the Fed’s ultimate response to the interest rate spikes that plagued the money market in 2019. If the Fed ends QT too soon, it may even risk discrediting the efficacy of these interest rate caps in the medium term.

The SRF Has Still Barely Been Used

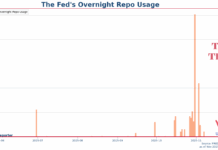

While the SRF is being increasingly used, it is still not lending out liquidity daily. The usage amount is also minimal, especially when compared to the non-standardized repo operations pre-SRF establishment.

As another comparison, the Overnight Reverse Repo (ON RRP) is still receiving several billion USD as deposits. Hence, the usage of the SRF is not significant.

The Risk of Stigmatizing SRF Usage

A potential problem with ending QT while the SRF hasn’t yet been seriously used is that the market may infer that the Fed is not comfortable with the interest rate ceiling tool acting as a regular overnight liquidity provider.

In such a case, continued usage of the facility would then be regarded as a signal that the Fed may soon lose control of the interest rates. This is the so-called stigmatization problem, which was a problem haunting the discount window, especially before the Fed’s improvement measures were implemented in March 2020.

The SRF could be more prone to stigmatization if not handled correctly as its aggregate operation results are published daily, instead of the weekly disclosure for the discount window.

We have already seen quite a number of commentaries online describing the slight increase in the SRF’s usage as “flashing warnings” in the repo market.

The SRF is supposed to be a solution to repo interest rate crises like the one in 2019, helping the Fed to contain spikes in overnight interest rates.

So far, though, it’s been used as a reason to “cry wolf.”

Discount Window is Also Relatively Calm

Under the Fed’s current implementation strategy, it charges the banks the same interest rate for SRF and primary credit at the discount window, both at the upper limit of the fed funds rate target range.

This was part of the Fed’s strategy to incentivize usage of the discount window during the Covid era, by removing the “penalty” pricing of 50 bps above the Fed’s benchmark interest rate target.

Pricing it at the upper range of interest rate target also allows the discount window to act as an interest rate control tool, putting another soft cap on the overnight market interest rates.

Primary credit, so far, is also not extensively used. It is definitely not at the levels seen in previous crises.

The BoE’s Ceiling Tool Usage as a Comparison

A point of comparison is the Bank of England, which adopted the so-called demand-driven (or repo-led) floor system.

The BoE has so far established two ceiling tools to provide liquidity to banks: Short-term Repo Facility for seven-day lending and Indexed Long-Term Repo for longer term liquidity.

The BoE successfully encouraged the usage of these two facilities. Short-term Repo is lending out more than GBP 83 billion weekly, while ILTR has loaned out close to GBP 40 billion. While they are not a dominant portion of the GBP 655 billion total reserves in the UK, they still account for close to 20% of reserve supply.

In comparison, Standing Repo Facility and Discount Window usage so far account for less than 1% of the Fed’s outstanding reserves.

Lorie Logan: The Fed’s Ceiling Tools Ain’t Designed This Way

In her speech in August, Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan explained the differences between the Fed’s current QT strategy compared to the UK’s repo-led approach. She said the US central bank is currently adopting a “glide path” approach — aiming to achieve a gradual landing on the ample level of reserves.

Logan is, in general, a believer in central bank ceiling tools. She explained in the same speech that central banks should allow a sustained shift up in market rates above the interest on reserves to squeeze excess demand for reserves.

“If the economic cost of funding from the ceiling tools modestly exceeds the interest rate on reserves, banks will have an incentive to bring reserve demand back down to the long-run level,” she explained.

In a way, though, she thought one of the reasons the Fed is not opting for a demand-driven floor system is that the US central bank’s ceiling tools are not refined enough for that purpose.

“At the Fed, while we have made strides in enhancing the effectiveness of the discount window and Standing Repo Facility, it would be worthwhile to consider further steps, such as increasing or removing limits on the SRF’s size or centrally clearing those transactions. So, I believe bringing reserves down gradually, while also making our ceiling tools available and encouraging market participants to use them when they are economically attractive, will be an effective strategy in the United States,” said Logan at the time, showing the Fed’s lack of confidence to allow its ceiling tools as significant liquidity providers.

The Fed Can Wait a Bit Longer

As we have calculated in a previous article, the Fed will likely not reach the benchmark 9% reserve-to-GDP ratio until April, the US central bank still has months (and five meetings, including the one this week) to prepare for the end of QT.

Moreover, one of the latest tools —reserve demand elasticity— created by the New York Fed to detect reserve supply’s distance to ampleness is still showing a reading close to zero (it should be negative when close to reaching ample). This should allow the Fed to wait a little bit more before closing QT.

In my opinion, the Fed should first opt to, as Logan has suggested, test and refine the capability of its two ceiling tools before drawing a close to this round of QT. This way, it can show to the world that SRF and discount window are more than capable to withstand normal fluctuations in the money market interest rates.

Even if the Fed chooses to draw the curtain for its QT program, the Fed should continue to encourage the banks to access liquidity with SRF. I think lowering the minimum rate of the SRF by like 5 bps can be a good way to achieve that.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡