Last Updated:

Quantitative tightening (QT) may reach its end point “in the coming months,” said Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell in a speech last week. What does it mean?

The Fed has long stated that the terminal point of QT is the so-called “ample” level of reserves — the minimum level of reserves necessary for the Fed to maintain interest rate control without active interventions — and Powell said such a point could be reached in months, rather than years.

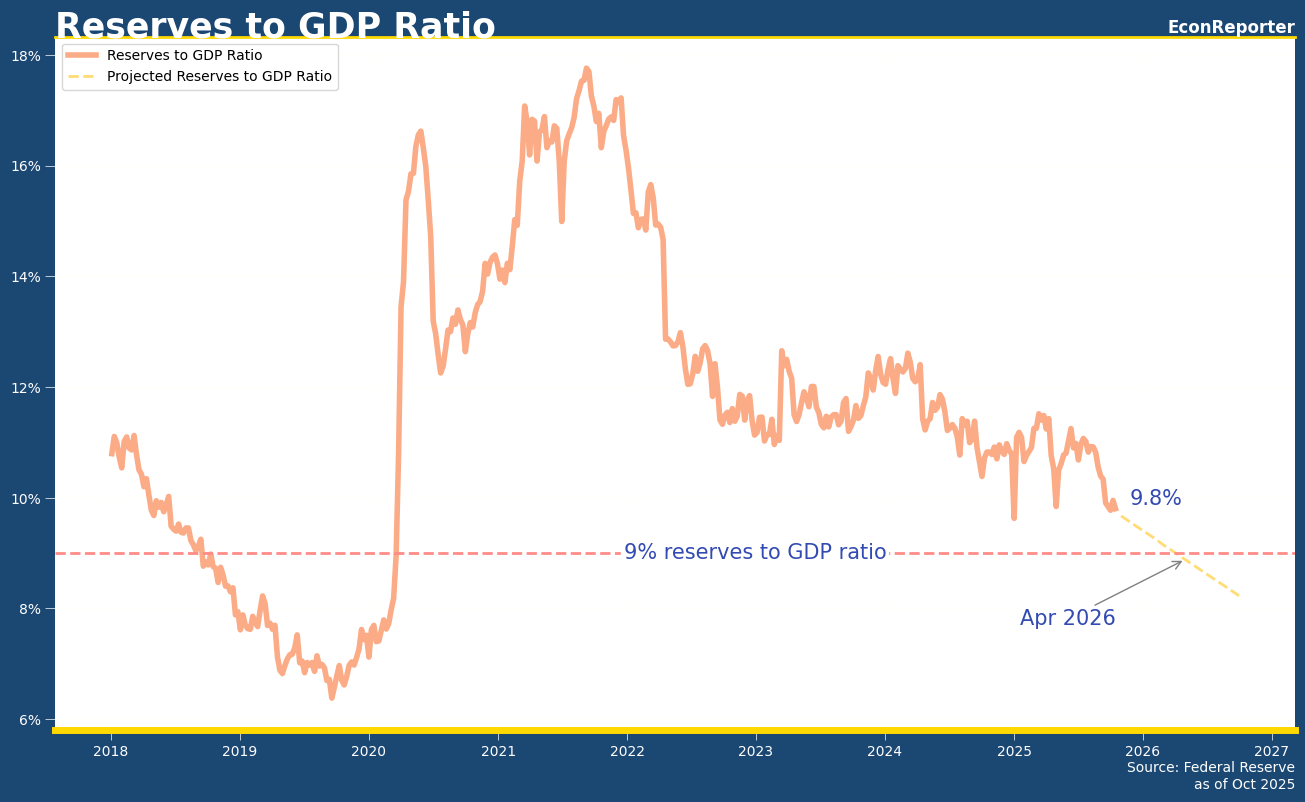

There is no exact numerical definition of “ample” but Fed governor Chris Waller in July offered a potential point at which ample might be reached: a 9% ratio of reserves to real GDP.

The logic behind this is that the previous round of QT, between Oct 2017 and Aug 2019, ended at a level below 8% and that was followed by an episode of repo rate spikes in Sept 2019. The fact that the Fed temporarily lost control of the money market interest rates was taken as a signal that the level of liquidity was too low: i.e. the point of ample was breached.

Waller regards 8% of GDP as a simple benchmark for ampleness and he thinks it’s best to add a small buffer on top of that level. Therefore, 9% is his preferred number.

The QT Math

The US’s real GDP level is about USD 30.5 trillion as of the end of Q2. 9% of that would be about USD 2,750 billion.

As the total supply of reserves currently stands at around USD 2988 billion, meaning the distance to 9% GDP is about USD 250 billion.

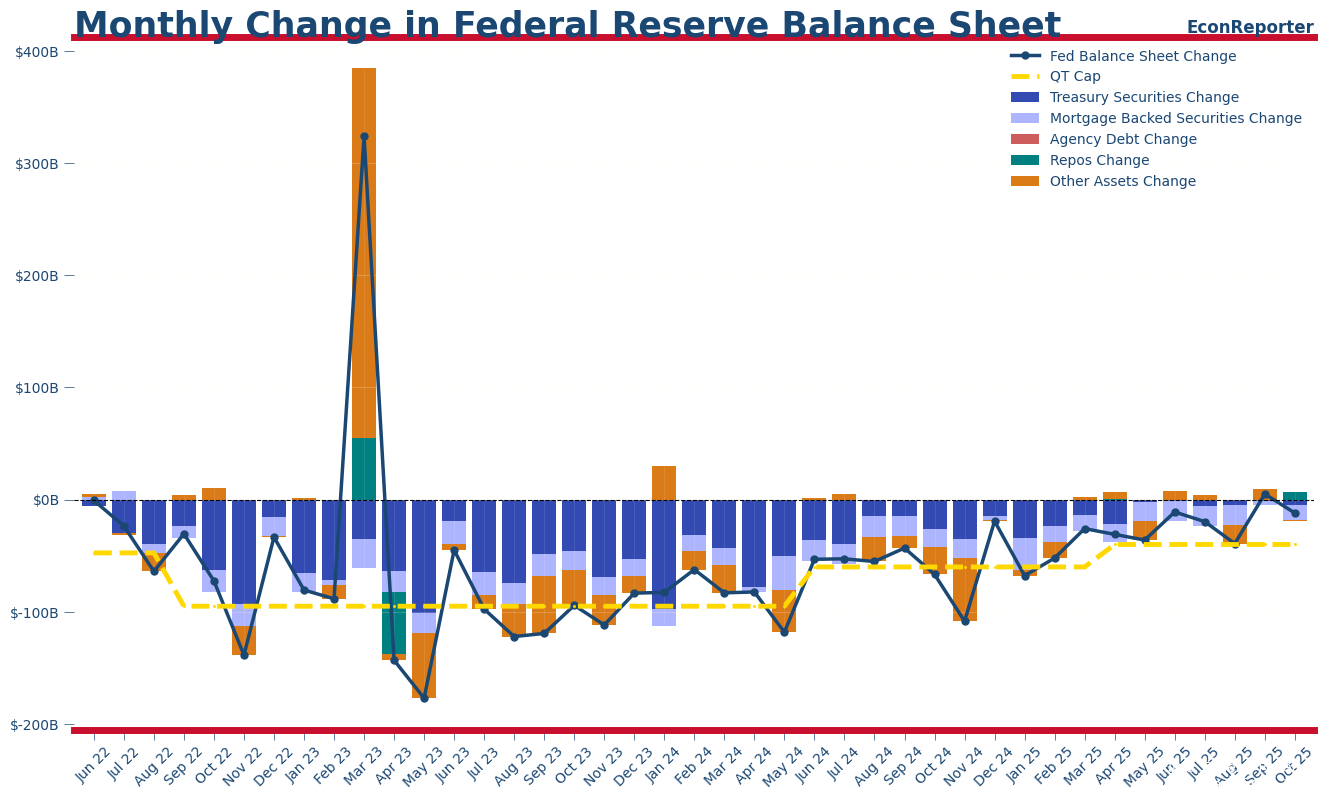

The Fed allows a certain amount of debt securities it holds to mature each month. Its current QT cap is USD 40 billion a month, comprising a USD 35 billion cap for MBS and a USD 5 billion cap for Treasury securities.

Assuming the level of reserves drops by exactly USD 40 billion a month, it would only take a bit over six months, or around April 2026, to arrive at 9% of GDP.

Was Powell thinking about Waller’s 9% reserve-to-GDP ratio?

The first thing we need to consider is whether Powell also had the 9% benchmark in his mind when he talked about “coming months” as the timeframe for reaching ampleness.

A piece of evidence supporting the case is in the footnote that directly follows the “coming months” passage, where he wrote:

Currently, reserve balances stand just below $3 trillion, or about 10 percent of GDP. By comparison, reserves as a share of GDP stood near 8 percent of GDP in early 2019, prior to the acute funding pressures that emerged later that year.

Here we can see Powell mentioned the current ratio of 10% and further implied the logic used by Waller, that 8% was the level that coincided with a funding crisis last time. This shows the 9% was in his mind when he said “coming months”.

It’s noteworthy, though, that Powell has refrained from directly mentioning the 9% figure. He also explicitly said that “reserves as a share of GDP is merely indicative, not a measure of the ampleness of reserves” to make sure that the Fed won’t be tied to a specific number and date at this moment.

We would, therefore, take the “9% rule” as an indicative threshold but not a definite endpoint of QT.

Will TGA and ON RRP Complicate the Reserve Reduction Again?

With other things being unchanged, QT should be able directly reduce the size of the reserve supply. In the real world, however, other things change.

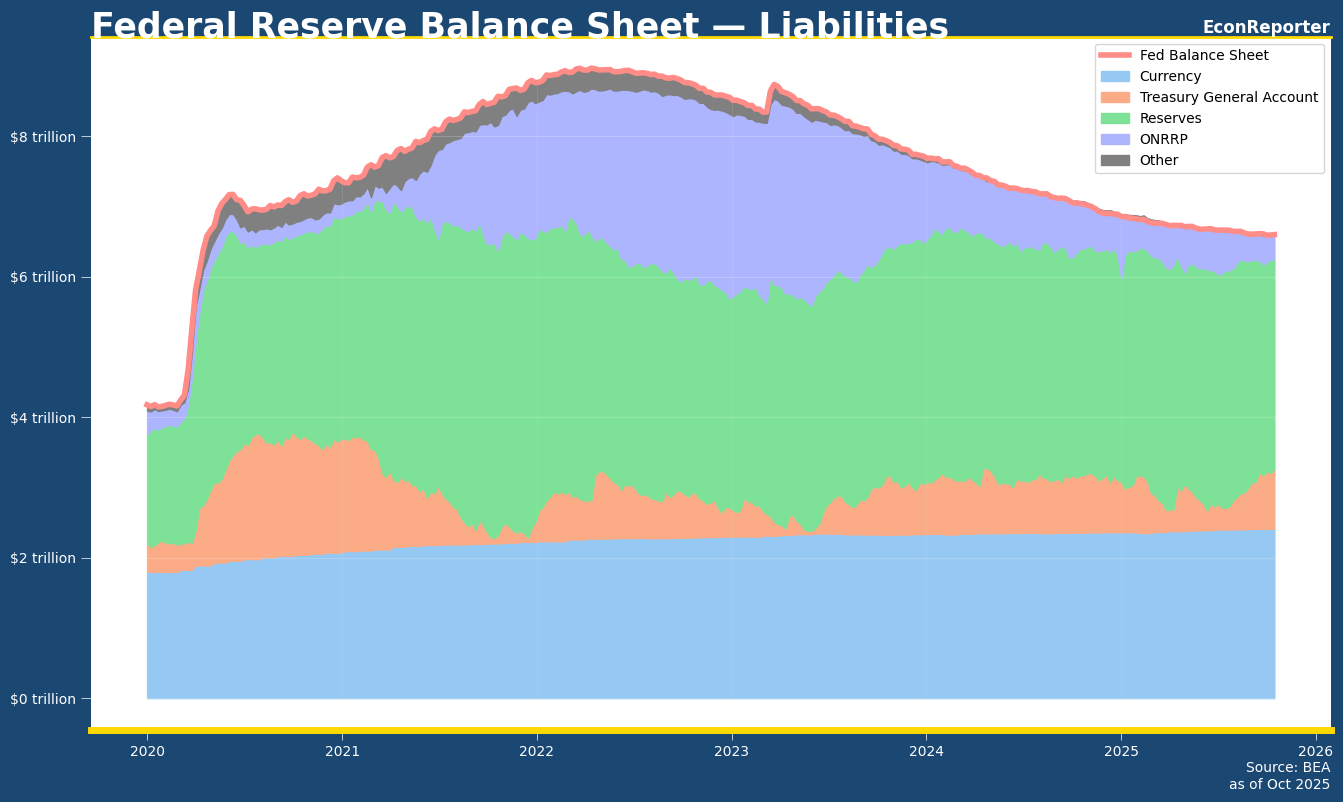

The “other things” in the liabilities side of the Fed’s balance sheet that often fluctuate are Treasury General Account (TGA) and Overnight Reverse Repo (ON RRP), making the relationship between QT and reserves a bit less linear.

TGA

TGA is the checking account the US Treasury holds at the Federal Reserve. When people pay tax to the government, for example, money transfers from their banks’ reserve account in the Fed to the TGA, hence an increase in the amount of money held in the TGA would usually reduce the amount of reserves, and vice versa.

The amount of liquidity the Treasury held in the TGA drained in the middle of this year, dropping to as low as USD 277 billion in June, as the debt ceiling became binding.

As the debt ceiling was raised in July following the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the Treasury worked hard to rebuild the TGA. This rebuilding process sucked a certain amount of liquidity from reserves, helping to bring the reserves below USD 3 trillion.

The Treasury has earmarked USD 850 billion as the cash balance it targets for the Q4, according to its marketable borrowing estimates published in July, so it’s reasonable to expect the TGA will remain relatively stable in the upcoming quarters and have minimal effect on the changes in reserves in the coming months.

ON RRP

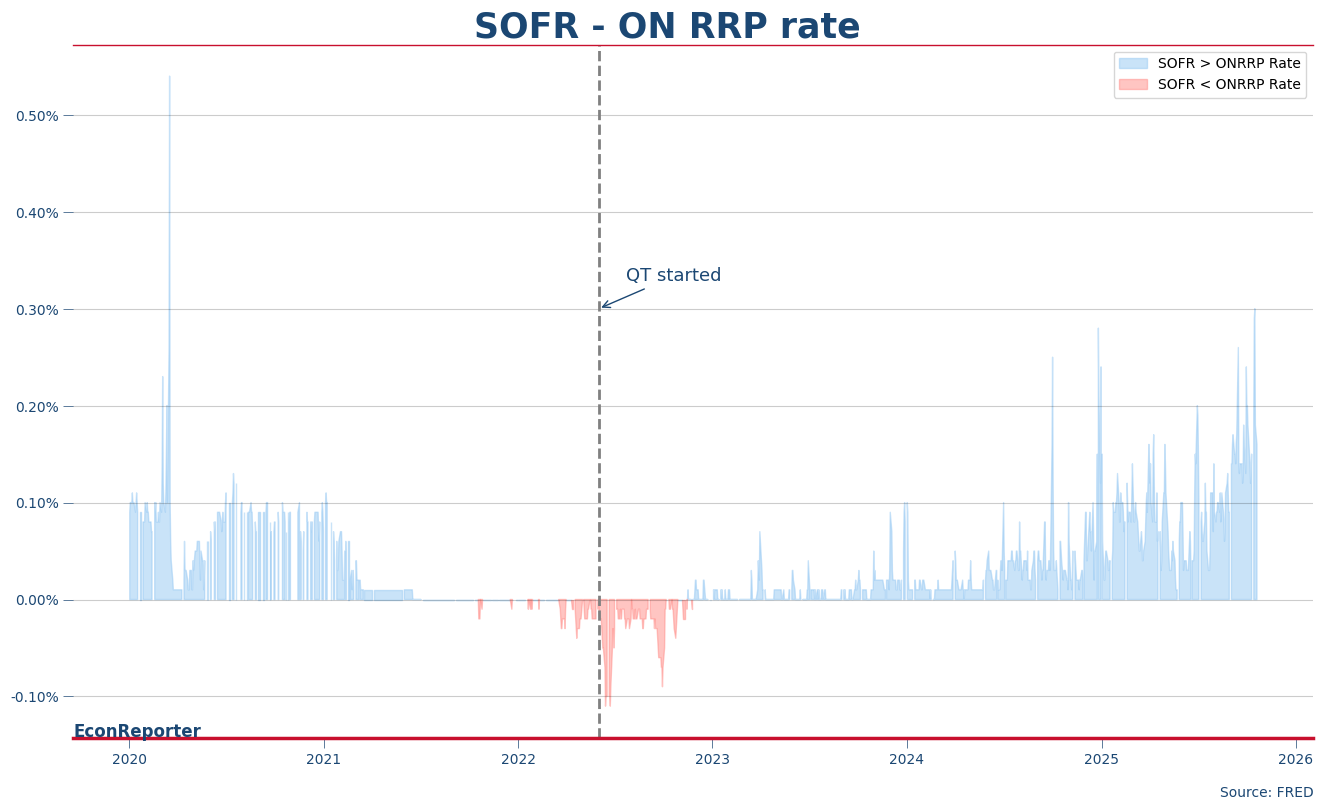

Another major item on the Fed’s liabilities side of the balance is ON RRP — a deposit facility opens to money market funds and acts as an interest rate floor that helps the Fed control market repo rates.

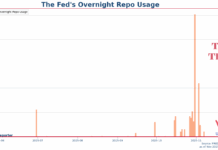

ON RRP usage at its height reached close to USD 2.7 trillion at around April 2023, but then usage dropped rapidly in the later half of 2023 as QT and a round of TGA rebuild (after a spell of debt ceiling constraint in the first half of 2023) started to drain excessive liquidity in the facility.

ON RRP usage is now less than USD 6 billion in October. As Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) remains higher than the ON RRP rate, there is no reasons to believe that usage of this deposit facility will rise again any time soon.

As Powell explained it in a footnote of his latest speech:

Since we began shrinking our balance sheet in 2022, the quantity of reserves has not changed much as the excess liquidity in the system was absorbed and then subsequently released by our overnight reverse repo facility. Now, however, balances in that facility have declined to minimal levels, so further declines in our securities holdings will translate more directly into lower reserves.

We should expect that ON RRP usage, like TGA balance, will no longer interfere with the reserve-reducing effect of QT in the coming months.

QT, from now on, should have a much more potent impact on draining “abundant” reserves.

QT Caps Are Never Fully Used

With TGA and ON RRP out of the way, does it mean the projection of reaching 9% GDP in April is a credible one?

There is still one more factor to consider: whether the Fed can use up its current QT cap in the coming months.

As we mentioned, the current monthly QT cap comprises a USD 35 billion for MBS and a USD 5 billion for Treasury securities. An important characteristic of this QT cycle is that the Fed almost never uses up its monthly QT cap.

| Date | Treasury Cap | MBS cap | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022-06-01 to 2022-08-31 | 30 billion | 17.5 billion | 47.5 billion |

| 2022-09-01 to 2024-05-31 | 60 billion | 35 billion | 95 billion |

| 2024-06-01 to 2025-03-31 | 25 billion | 35 billion | 60 billion |

| 2025-04-01 to now | 5 billion | 35 billion | 40 billion |

The yellow dash line in the graph above represents the combined QT for each month, which is almost always higher than the amount of Treasuries (dark blue) and MBS (purple) they allowed to mature. This means that a USD 40 billion monthly run-off projection would likely be an overestimation.

This makes reaching the 9% reserve-to-GDP ratio by April 2026 more like the earliest estimate.

Conclusion

Now that Powell unleashed the expectation of ending QT within months, there is no backtracking. Furthermore, as Powell emphasized, the Fed’s “long-stated plan is to stop balance sheet runoff when reserves are somewhat above the level we judge consistent with ample reserve conditions,” so they can stop even when ample is not apparently reached.

The Fed’s plan for post-QT balance sheet management is also a point to which we should pay attention.

In another footnote in his speech, Powell reiterated one of the principles of the Fed’s balance sheet normalization policy:

Once balance sheet runoff has ceased, reserve balances will continue to gradually decline as other Federal Reserve liabilities grow over time. At some point, the Committee will determine that reserve balances have reached an appropriately ample level. Thereafter, the Committee will manage securities holdings as needed to maintain ample reserves over time.

That is to say, the Fed will encourage further reduction in reserves even after QT ends. It would merely change the strategy from reducing the assets it holds to changing the compositions of the liabilities. For example, it can allow a gradual growth in currency in circulation to substitute for reserves, giving the level of reserves an even slower march to the point of ampleness.

As Powell’s chairmanship will end May next year, he may prefer to draw a close to the QT era before he goes and leave any further technical adjustments to the next chair. (Though, there is still quite a chance that Powell will stay on as Fed governor beyond his term as chair.)

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡