In a recent NBER working paper “Monetary Policy Communications and their Effects on Household Inflation Expectations“, economists Olivier Coibion, Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Michael Weber tried to find out how the household’s expectation for inflation change with regard to the information they received.

The three economists conducted a randomized controlled trial which sent 80,000 household members of the Kilts-Nielsen Consumer Panel (KNCP) three waves of surveys in June, September and December of 2018.

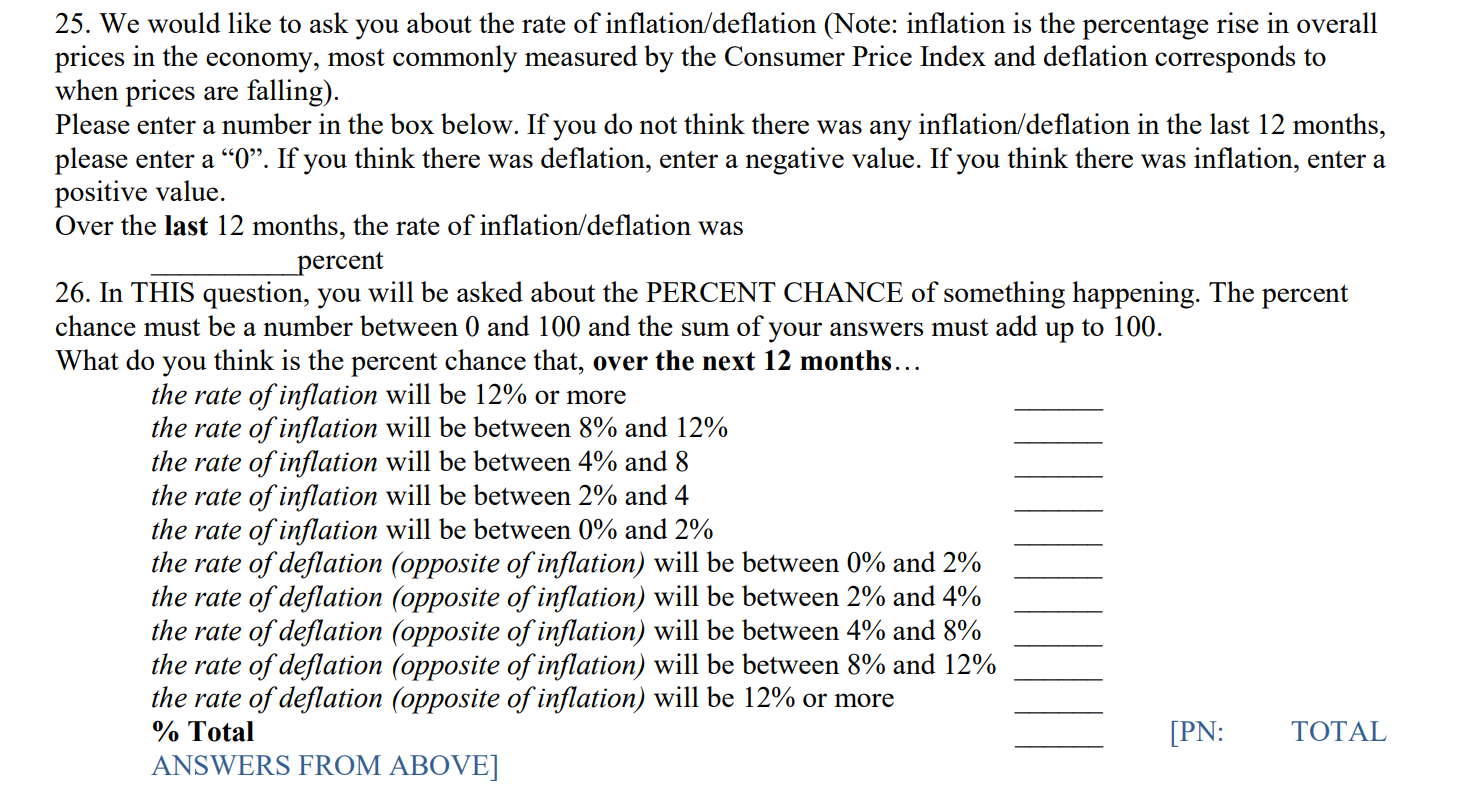

In the June 2018 survey, they first ask individuals about their perception of the inflation over the previous 12 months. Then they ask the participants their expectations for 12-month-ahead inflation, not in a single number but in form of assigned probabilities to different levels of the inflation rate (see below).

Then respondents were then assigned to one of nine groups — one control group and eight treatment groups. Different treatment groups are provided with different information:

- the actual CPI inflation rate over the last twelve month (2.3%);

- the inflation target of the Federal Reserve of 2% per year;

- the FOMC forecast for inflation in 2018 of 1.9% (also informed participants that the FOMC is responsible for setting short term interest rates);

- the most recent FOMC statement;

- the coverage of the most recent FOMC decision in USA Today;

- the most recent unemployment numbers;

- the national average gas price inflation over the previous three months of 6.4%;

- the actual fact that the U.S. population grew by 2% over the last two years as a placebo treatment.

After reading the treatment information, respondents were asked again to put down their inflation forecasts and perceptions — but this time they are required to write it in form of a single point estimate so that they won’t feel that they were answering the exact same question for the second time.

The economists would like to find out if some simple statistics might help individuals update their inflation expectations, and if the effects persist in the second and third wave of surveys.

First of all, they found that average 12-month ahead inflation expectations and perceptions of all individuals in the survey prior to any information treatment being applied are 2.5%. However, there is a wide dispersion in the estimates, with a standard deviation of 2.6%.

One interesting related preliminary finding is that, when respondents were asked what inflation rate the Fed was trying to achieve in the long-run, less than 20% of respondents correctly answered 2%.

In fact, less than 50% answered a number ranging from 0% to 5%. Almost 40% answered that the Fed was targeting an inflation rate of 10% or more! This suggests the households’ lack of knowledge about the objectives of the Fed.

The main objective of this research, however, is to find out the average change in expectations of respondents in the treatment group relative to the average change in the control group.

For the three groups that were told the most recent 12-month CPI inflation rate (2.3%), that the Federal Reserve targets an inflation rate of 2%, and that the FOMC was forecasting an inflation rate of 1.9% over the next twelve months, the effects are very similar. All three reported a reduction in the average inflation forecast by 1.0-1.1%, relative to the control group.

That is, these very simple information treatments can have large effects on the beliefs of the individual.

However, the effect is not persistent. Three months later, the average expectations of these treated individuals are still lower, but the effect has dissipated by about 75%. The effects have fully dissipated after six months.

For the treatment group that was presented with the entire post-meeting FOMC statement, it has approximately the same effect on inflation expectations as the previous three treatments. The average forecast reduced by 1.2% relative to the control group.

However, the effect of reading the FOMC statement dissipates more rapidly, having no discernible effect on expectations relative to the control group after three or six months.

As of the treatment group which was presented with a news article from the USA Today covering the same FOMC meeting, participants who read the news article reduced their inflation expectations by only 0.5% relative to the control group, less than half the effect of any of the other inflation-related treatments.

Despite the fact that the article seemingly transmits the same information as the other information treatments, it seems that households think that information coming from the news media as being less reliable, so it has less impact on the expectation revisions.

However, its effect is relatively longer-lived. Three months after reading the article, the average effect on expectations remains half of its instantaneous effect, but it too dissipates fully within six months after the information treatment.

A noteworthy finding from the group which respondents were told that that national gasoline prices rose 11% over the previous three months. This information leads to an immediate upward revision in households’ inflation expectations of approximately 1.4-1.5% relative to the control group!

The three economists said this translates into a pass-through from gasoline spending to overall expenditure of about 10%, well above the average expenditure share of gasoline in consumption of 5%. It seems that people are over-estimating the impact of gasoline inflation to the overall inflation.

A similar situation happened in unemployment’s effect on inflation. First, the average perceived unemployment rate for all respondents in the first wave was 6.3%, with a standard deviation of 3.9%. Only 12 percent of respondents report unemployment rates less than or equal to 3.9%. Hence, when respondents in this group were told the actual value of the unemployment rate in the previous month of 3.9%, they were almost always being told that the unemployment rate was significantly lower than what they believed.

As you might expect, the downward revision of their unemployment rate estimate will lead to an upward revision of their inflation, as the logic of Phillips Curve told us. Sorry to disappoint you. No. In fact, the result was an immediate downward revision in their inflation expectation of 0.3%.

As you can see from all the results above, there is a huge discrepancy between what economic authorities expect people to know, and what they really know. The sad news is, as showcased by the USA Today treatment, the media doesn’t seem to have the power to encourage people to revise their expectations. Also, people don’t seem to care about the Fed’s objectives and activities. This might not be good news for the Fed if they plan to rely on forward guidance to be a major monetary policy tool.

The good news is, just provide the people with some simple economic statistics, the people are willing to adjust their expectations accordingly.