Last Updated:

Welcome to “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century”, an interview series that explore the evolution of the post-Great Recession Macroeconomics.

We are honored to have Jeremy Stein, the Moise Y. Safra Professor of Economics at Harvard University and former member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, to explain his recent research “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet as a Financial-Stability Tool” (coauthored with Robin Greenwood and Samuel Hanson).

This paper put forth the most widely-accepted argument for the Fed to maintain a sizeable balance sheet going forward. As Prof. Stein explains below, financial market stability could be at risk if too much of the supply of safe assets is from private sector providers. They argue that the financial system would be safer if the government can provide more short-term safe securities to satisfy investors’ demand and crowd-out private sector issuances.

Why do they think it the Fed who issues more reserves for investors? Why can’t Treasury take up the responsibility? More importantly, does it actually mean that the Fed’s balance sheet has to be “sizeable” forever? Prof. Stein will tell us more about all these in the interview below.

Q: EconReporter S: Jeremy Stein

| The transcript is edited for clarity. All mistakes are ours. |

Why money-like instruments are potential threats to financial market?

Q: In your paper “Using the Federal Reserve Balance Sheet as a Financial Stability tool,” the main argument is that more government provided short-term financial assets available in the financial market, it would make the financial market safer. Why do you think that private sector supplied money-like instruments are potential threats to the financial market?

S: What we saw in the run-up, and the subsequent unwind, of the financial crisis is that one of the problems was that financial firms had issued a lot of very short-term debt. Some were insured, but a lot were uninsured. When their solvency started to be under question, there were effectively run-like phenomena, both on some of the standard intermediaries, and a lot in the so-called shadow banking system.

For example, one of the early manifestation of the crisis was a very rapid shrinkage of the asset-backed commercial paper market. These were vehicles that have issued short-term commercial paper backed by the mortgages and other assets. That essentially is a form of short-term funding.

Our argument is that these kinds of things are encouraged by the fact that there is not that much government paper. As a result, these sorts of short-term claims are very highly-valued in the marketplace, which is another way of saying they have relatively low interest rates. So, private sector players are tempted to issue a lot of them.

What we found is that when there are more securities like treasury bills outstanding, there tend to be less private sector securities like commercial papers, and so forth. So the basic idea is that if the government makes more, it will crowds out the private sector to some extent, and that has a useful financial stability function.

Is RRP better than IOER and T-bills?

Q: Your argument also suggests a greater role of the RRP (Reverse Repurchase Program) in the Fed’s monetary policy regime. Why do you think the RRP is superior to T-bills and IOER?

S: I think the basic argument is that, somehow, some part of the government should provide something that looks like T-bills. At the highest level, we were just arguing for something like more T-bills provision. That could be done by the Treasury Department. On the one hand, that would be the most direct thing that you could imagine; but on the other hand, the Treasury has been reluctant to issue the volume of T-bills that we might have in mind. Just to give you an example. Roughly speaking, there are about 400 or 500 billion dollars of T-bills out there with the maturity of less than 30 days. If you compare that to the Fed’s balance sheet, which is several trillion dollars, the Fed has been more willing to make short term claims available.

One reason for that may be that the Treasury worries about the “rollover risk.” For example, if there are 2 trillion dollars of 30-day T-bills outstanding, they’ll have to run an auction for 2 trillion dollars every month. They will be worried that auction potentially not going well and not able to roll-over their T-bills.

That same problem does not arise when you are the Fed because the Fed creates the final means of settlement. The Fed creates money. In some sense, they will never have a failure to be able to honor their obligations. That maybe an argument for the Fed doing it as opposed to the Treasury.

Now, if you do have the Fed do it, the Fed can create the reserves or produce the RRP. Reserves in the modern monetary system pay interest so you may think of them as kind of overnight bills. But the interest they pay on reserves can only be received by banks. Or say it a little differently, only banks are allowed to deposit at the Federal Reserve. Compared to the T-bills, which can be broadly-held by anybody in the marketplace; reserves are like a very restricted form of T-bills. So that is less desirable if you’re trying to have this crowding-out effect that we have discussed.

In that sense, RRP is a little closer to what we might think as the ideal, which is the Fed itself issuing some form of bills. It’s closer because money market funds and others can buy and hold Fed’s RRP. From the perspective of having the crowding-out effect, the RRP works better because it can be more broadly-held. But the sort of “high-level thing” is that we would like to have some part of the government creating widely-holdable short-term claims.

What is RRP?

FAQs: Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement Operational Exercise – FEDERAL RESERVE BANK of NEW YORK

Working within the Federal Reserve System, the New York Fed implements monetary policy, supervises and regulates financial institutions and helps maintain the nation’s payment systems.

Q: Under your proposal, do you think there is any need for reforming and improving the RRP? For example, should the Fed open it to more participants? If so, to whom should the Fed open the RRP?

S: I think I agree with the premise of your question. If the ultimate goal is to create something that looks like T-bills and created by the Fed, you want it to be widely available.

One restriction I might make is to open it only to government-only money funds. That’s a quite simple way to make it available to everybody. The money fund is sort of “mile reaper” on this. The RRP goes into a money fund, the money fund may charges investors 10-20 basis points, and then anybody can invest in the money fund.

One way to think about it is what fraction of the interest that the Fed pays on the RRP get ultimately pass through to households.The problem with reserves is that it has to be intermediated by the banking sector. So there is a big wedge between what the banks get from the Fed, and what the bank’s depositors get from the banks. With something like a money fund structure where you get a reasonable degree of competition, it would mostly get passed through. The interest that the Fed pays goes to the Mum and Pop at the end of the day.

So my vision is that I don’t think you need to change it dramatically. Just try to encourage as much competition from money fund-like vehicles as possible, and that would get us most the way there.

Why the Fed should keep a sizeable balance sheet?

Q: Is it necessary for the Fed to have a sizeable balance?

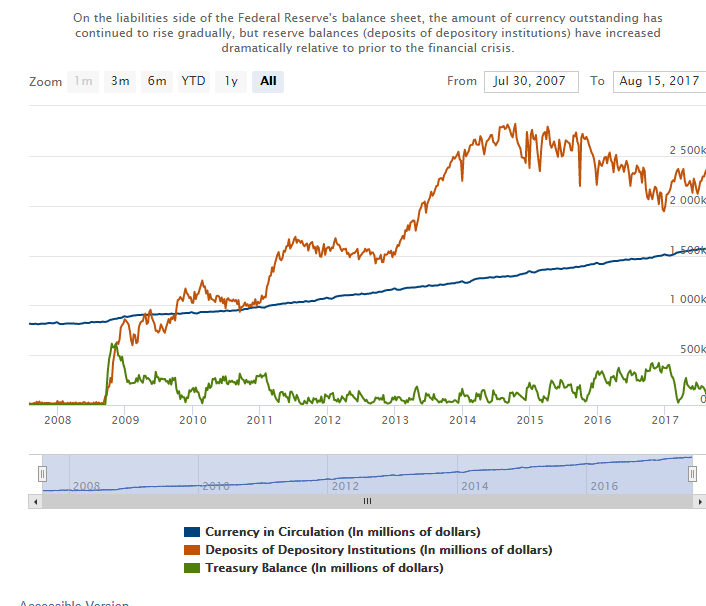

S: I think the gist of our argument is that if you want the Fed to supply couple trillion of dollars of RRP, you need its balance sheet to be big enough. Take a simple example, if the currency has to be 1.5 trillion, and on top of that you want some reserves and 2 trillion of RRP, then you will need the balance sheet to be on the order of 3.5 trillion, or more. So you do have to have a nominally large balance sheet.

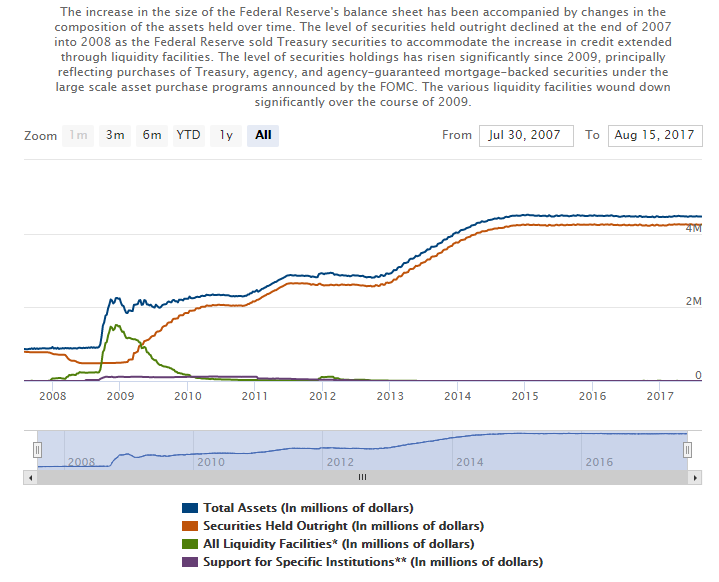

The argument we made in the paper is you don’t necessarily need the Fed to hold as much interest rate risk as it does right now. Right now, the Fed not only has a large balance sheet, but on the asset side, it has bonds with the average maturity of 8-9 years. So the Fed is taking a fair amount of interest rate risk. For some purposes, the right definition of the size of the balance sheet isn’t really just in the dollar amount, but in the unit of interest rate risk. One thing that we’ve suggested is that even if you keep the size roughly like it is, or you bring it down just a little bit, you can still bring down the maturity of the assets the Fed holds quite considerably. So, instead of holding on treasury securities with eight or nine-year average maturity, you hold three-year average maturity. Even the size of the balance sheet is the same; you can cut the interest rate risk or the duration exposure by a factor of three.

I think the more principle concern if somebody has a concern of the Fed’s balance sheet being too big, that concern is better expressed in terms of how much interest rate risk they are taking, rather than just the nominal size of the balance sheet. On the former definition of size, you can make better progress.

Q: What I meant is that many people are now talking about certain “terminal” size for the Fed’s Balance Sheet, for example, around 2.5 trillion dollars. People seem to be saying that 2.5 trillion would be the size of the balance sheet for a very long time like it would be fixed at that particular level “forever.” But in your proposal, if I interpreted correctly, the size of the balance sheet should depend on the demand for safe assets in the financial market. Am I right?

S: Absolutely. I don’t think you need to target a certain quantity size of the Fed’s balance sheet.

In an ideal world, the Fed and the Treasury together would be looking at various market indicators and trying to get a sense if there is a scarcity of safe assets. For example, one indicator that we pointed to is the slope of the very front-end of the yield curve. If there is a very big difference between the rate of one-week T-bills and six-month T-bill, that is telling you there is a shortage of the very short maturity securities.

In some sense, what you are doing is you would like to target that spread and make sure it is not getting too big. That doesn’t necessarily correspondent to a fixed size of the balance sheet, but it might correspond either to the Fed’s willingness to expand the balance sheet when needed, or the Treasury’s willingness to pay attention to the spread and issue more T-bills.

Q: How should the Fed fill the asset side of its balance sheet?

S: In principle, central banks hold all kinds of assets, not just government bonds. The Fed, as compared to other central banks, is relatively constrained by law regarding what it can hold. It is only allowed to hold either treasury securities, or government insured securities, like agency bonds and government backed mortgage-backed securities (MBS). So they are already dealing with a somewhat limited set of instruments. I think there has been a traditional preference for the Fed to focus on treasuries.

Obviously, they brought a lot of MBS during various Quantitative Easing (QE). But I think that there is a view that it is done under relatively extraordinary circumstances. It has allocated credit toward the housing sector, which I think some prefer not to do. So, a more neutral policy would be the one that the balance sheet is filled mostly with treasuries.

Does a sizeable Fed balance sheet mean helicopter money?

Q: Does maintain a larger Fed Balance Sheet with treasuries on the asset side of it constitutes a “helicopter money” operation, in a certain sense?

S: No, I don’t think so. The traditional open market operation is that the Fed prints money and uses that to buy securities from the household sector. If you think about the wealth of the household sector, it is not going up; they are just getting money for their bonds. They are just holding wealth in a different form.

Helicopter Money is basically the Fed going out and buying goods. Or put it a bit differently, it’s giving household money but not getting anything in return. It is like pairing a tax cut with the government buying the bonds. As long as the Fed buys the bonds and as long as those bonds are not written off, I think it is standard monetary policy. it would be helicopter money if the government issues a special kind of bond that only the Fed bought and that never pays any interest, and never pay back any principal.

As long as it is buying conventional government bonds and it is receiving the same interest as everybody else, it is not really “Helicopter Money.” It is conventional monetary policy. There is no fiscal aspect of it.

Q: One major difference between RRP and T-bills is that the interest rate of RRP is not market determined. Would that be a concern for your proposal?

S: I think the one place we have to be a little careful is how the RRP program would behave in the time of stress. Here is the concern people have about the RRP program.

Think about a crisis scenario when everybody is nervous, and they want to run to safe assets. People want to run to the government. With T-bills, where the price is market-determined, and the quantity is fixed, so in a panic when everybody wants T-bills, they buy T-bills, and the price of it goes up, the interest rate of the T-bills goes down. We’ve seen T-bills with negative rate during times of severe market stress.

What’s good about that is that when the T-bill rates go down, it is an automatic stabilizer because the panic means you need to have an increased spread between T-bills and, say, commercial paper. But here the way you get the spread going up is that the T-bill rate goes down. As a result, the commercial paper rate doesn’t have to go up by as much, which prevented the panic from getting worse.

If you take RRP and make it infinitely available at a fixed rate, what’s going to happen instead is that if the rate of the RRP doesn’t go down when there is a panic, the rate of the commercial paper would have to go up much more. Or said a little bit differently in quantity terms, because the quantity of RRP expands, to keep the rate constant, people can drain all their money out of commercial paper and just put it infinitely with the government. That’s a real concern.

I think the way to address it is to try to recover some of the more stabilizing property of T-bills by having the following things. Fix the rate and let the quantity vary, but never let the quantity expand too rapidly in a stress situation. The way to do that is to have the RRP program as is currently design, but cap it. Instead of having the cap be just a one-time fix cap, you have it be some moving average.

For example, we can set the cap as no more than 120% of the last six-month average. In calm times, you set the price and let the quantity find its level. But then in a stress scenario, you never let the quantity expand too fast. It becomes more like fixed quantity T-bills, and then the price will adjust rather than the quantity.

Inside the RRP mechanism, they already have the capacity to do this because every day they get the demand curves from market participants. With those demand curve, they can either fix the price and let the quantity adjust or fix the quantity and let the price adjust. So it is just a matter of flipping over when things get a little bit stressed.

Responses to George Selgin’s against argument

Q: George Selgin of Cate institutions has recently argued against your proposal in a recent Macro Musing podcast. He thinks that the problem is not how to satisfy the demand of Safe Asset, but to remove certain restrictions that artificially lifted the demand for Safe Assets. For example, he mentioned IOER and liquidity requirements as some of the reason the demand for safe assets are artificially higher. Do you have any response to it?

S: I think it is a fair general point and it is a fair criticism. We have taken as given the demand for safe assets. Well, you know, the world demands a certain amount of safe assets, and somebody is going to have to supply them. It is going to be the private sector or the government. We prefer to have the government to do a little bit more.

It is a fair question to ask where all the demand is coming from. Some of it probably is what you might think of as legitimate demand, and some of it is the demand that could be induced by various forms of regulations or distortions. If that is the case, I think it is fair to ask if you can adjust the rule.

To give you a different example, a lot of demand for money-like stuff comes not from household but Corporate America, the big companies that have these enormous cash balance that they are holding. Some of it makes its way into demand for money funds and drive what we have been talking about. It is plausible to think that some of that in turns has to do with tax stuff.

For example, we know that one of the reasons that companies hold huge cash balances is when they make money abroad, if they don’t bring it home and don’t pay it out to the shareholders, they don’t have to pay tax on it essentially. So there has been a tax motive for them to pile a lot of cash. It may be that once we get rid of that tax distortion, all else equal, the demand for safe short-term securities would go down. So, I think that is a fair point. I think if you can take global policy view on some of this stuff, it makes sense to attack it on all dimensions.

Now, of course, the Fed can’t change tax policies. But I certainly agree that if tax policy would change, the Fed, or the Treasury, might not have to do as much in term of the size of the balance sheet and the supply of T-bills.

Q: Under your plan, the Fed will maintain a sizable balance sheet. Do you think that it would have effect or concerns on the international dimension?

S: It is a good question. My instinct is that it matters for all the reasons that QE matters.

Back to our previous discussion, it is not some much about the dollar size, but the impact of them on the asset prices. If they use their balance sheet to buy long-term bonds, and that pushes down the long-term interest rate, then I think we have seen pretty clearly that there is an effect on the exchange rate, and so forth.

I think if they go for a more neutral policy which on top of setting the short-term rate, the assets they hold is relatively short term in nature; given the short policy rate that they set, I don’t think there would be as much incremental effect on the exchange rate. The policy rate would always be important, for the usual reasons. But I think you can make it incrementally neutral, or closer to neutral in any event.

Of course, there is the level thing. In other words, we are talking should the Fed shrink the balance sheet by a lot or by a little. Obviously, to shrink it by a lot, that would have a bigger effect one-off; but if from that point forward it kind of stays constant, it is not going to have any further incremental effect on the exchange rate, or the international conditions more broadly.

The international dimension

Q: But do you think the size of the balance sheet itself has effects on the international dimension?

S: I think it does. If you think about the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, I think one of the reasons that they have expanded their balance sheet aggressively at the zero lower bound has been to weaken their exchange rates. I think that has been an important part of the transmission mechanism.

Clearly, they might affect some of the domestic activities, but I would guess a big part of why it has been attractive for Japan and Europe has been for exchange rate reason. That is clearly a significant part of the mechanism of why QE has been attractive to them.

Q: Several years ago, John Cochrane suggested a “Run-free Financial System” where all banks and financial corporations loans need to be 100% backed by the short-term treasury. It is basically the Chicago Plan. Comparing his proposal with yours, in which I think they shared certain similarities, what are the differences?

S: As you’ve said, I think there is a little bit of similarity, which is to say that there is a lot of short-term stuff out there and it is nice for the government to be involved and providing some of them. But Cochrane’s proposal takes that very very far.

The overall size of the US banking system… let’s just make some numbers up and call it 10 trillion dollars. So there are 10 trillion dollars of deposit or short-term funding out there, most of them are not backed by government bonds because most of the bonds are held by mutual funds and bond funds. We have supplied 10 trillion dollars of this money that people valued, and most of them are backed by loans or other assets.

The kind of Cochrane’s vision is that what the banking system fundamentally does is to make loans. Then we will have only the government supplies the safe assets. But that reduces the supply of safe assets dramatically. There is going to be only trillions of dollars safe assets left because there is just not as much if you don’t allow them to be backed by things other than treasuries. We have to cut the supply radically.

It sort of imagines that there is no value to the production of these safe assets and all you care is making loans. Whatever amount of T-bills the government supply, that is going to be the entire stock of safe assets. I think that is a bit of misunderstanding of what the financial system does.

One of my colleagues at Harvard Business School, Adi Sunderam, and some of his coauthors just produced a paper [The Cross Section of Bank Value, coauthored with Mark Egan and Stefan Lewellen]. To explain it in oversimplified terms, it says that basically 2/3 of the values that are created by the banking system is not coming from the lending side; it is coming from essentially creating deposits and safe places for people to put their money.

John’s proposal would radically reduce the supply of things like deposits. If you think that is where the values are coming from, then you need to be a little bit concern about that.

So I think of our plan as a very gentle step in that direction, which is telling the government, “You should help more.” But it doesn’t try to outlaw the other stuff. It just said, “If the government helps a little bit more, the private sector will do a little bit less of the other stuff.”

It has a bit of narrow banking spirit, but it is not mandating. The RRP is like offering a narrow banking alternative, but it is not saying that is the only way that the world can work.

Q: This paper was presented at the Jackson Hole last year, that means most Fed officials have heard of your proposal. As far as you know, how well the paper is received among economists in the Fed?

S: I don’t know, and I can’t speak for anybody in the Fed. But clearly, they are moving to shrink the balance sheet. If you think that the strongest level of our proposal was: “Don’t shrink the balance sheet!” Then obviously, nobody was listening. (Laughter)

But there is one thing they haven’t done. The Fed specified the pace of which they will shrink the balance sheet, but they haven’t nailed the end-point. I think there are some of the people in the Fed who want to shrink the balance sheet all the way back, and others that would like to leave an extra several hundred billion of reserves in the system. Obviously, those who are willing to leave several hundred billion of reserves in the system are closer in spirit to our plan.

If I am at the Fed right now, and I am trying to win the argument, I might not try to win it up front. I might say, “Well, let’s see how things go. I am going to predict that as the balance sheet shrinks, we are going to start seeing some strains in the money markets. We are going to see the yield curve gets very steep at the front end. If we see that, let’s keep an open mind and think about how we will respond.” I think those who argue to keep an open mind and to look at how things develop are at least keeping options open somewhat in the spirit of what we were thinking.

The other thing is how the Treasury will respond. You could imagine if the Fed shrinks the balance sheet, and in the process of shrinking, they started to see the treasury yield curve getting very steep at the front end. If the treasury takes more notice of that and starts issuing more T-bills, then they are behaving basically in the spirit of our proposal.

So we have tried to make this argument in a way that basically both the Fed and the Treasury can see some of the things that they should be looking out for.

Q: In my previous interview with Narayana Kocherlakota, he has several radical reform suggestions for the Federal System. I would like to see if you have any opinion on them. One of his proposals is to trip the FOMC vote from the NY Fed, so to avoid the problem of groupthink between NY Fed and Fed Board; What do you think about that?

S: I think this has to be seen as a broader set of issues. There are a variety of people objected to the Regional Bank Presidents, not just New York but any of them, voting on monetary policy, given that they are not confirmed by the Senate.

For example, Daniel Tarullo, my colleague at the Fed, who is a legal scholar, has been concerned, I think, with that aspect. There are other legal scholars have written about that.

Not being a lawyer, I am not as sensitive to the legal arguments. I would say it is an unusual structure, but I think it has its virtues. The virtues that I see of having both New York and any other reserve bank presidents are that it brings somewhat different views.

You know, everybody in Washington kinds of works in the same building, and we all have the same staff, and the staff really work for the Chair. For example, as a governor, I myself did not have a lot of independent staff resources. I depend on the same staff that was serving Chairman Bernanke and Chair Yellen.

Whereas if you are the President of the New York Fed or the Minneapolis Fed, as Narayana was, you have your own staff, which you can ask them to do a bunch of works that is contrarian, that takes a different view. I think that is valuable. Whether or not they are Senate appointed is a separate issue. But I think it is valuable to have these different people coming from different parts of the countries; they are listening to different inputs. They are availing themselves of somewhat independent analysis. I think all that has been largely healthy.

Whether the New York President should have a special role relative to the others, I don’t have a strong view. They do have the Desk, so I think they are deeply involved in the implementation of monetary policy. When you do QE, all the implementation is done by the Desk in New York. In that role, I would just say I am not bothered by it.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project dedicated to providing top-notch coverage on all things economics.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡