Last Updated:

Welcome to the latest installment of our interview series “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?”

“Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?” is an interview series which we ask top economists a very important question: “Why haven’t economists come up with a new General Theory after the Great Recession?” We want to know how the macroeconomics academia has evolved since the Great Recession, and why the responses from macroeconomists since 2008 are different from their counterpart in the 1930s.

In this installment, we make an interesting “detour”. Instead of discussing major macroeconomics topics, as usual, we invite a guest to discuss the issue of inequality with us. Our honorable guest is Branko Milanovic, Visiting Presidential Professor at the Graduate Center of City University of New York. The topic of this interview is his latest book “Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization” and how the research on inequality can be related to the study of macroeconomics.

In the first part of the interview, we will first focus on Prof. Milanovic’s new idea – the Kuznets Wave – and how to use it as the framework to analyze the future development of global inequality. In the second part of the interview (soon to be published), Prof. Milanovic will try to explore how the Kuznets Wave can be related to macroeconomics.

(The interview is edited for clarity. All mistakes are mine.)

Photo Credit: Brookings Institutions Youtube

Q: EconReporter M: Branko Milanovic

Q: What is the Kuznets Waves? How does it different from the original Kuznets Curve?

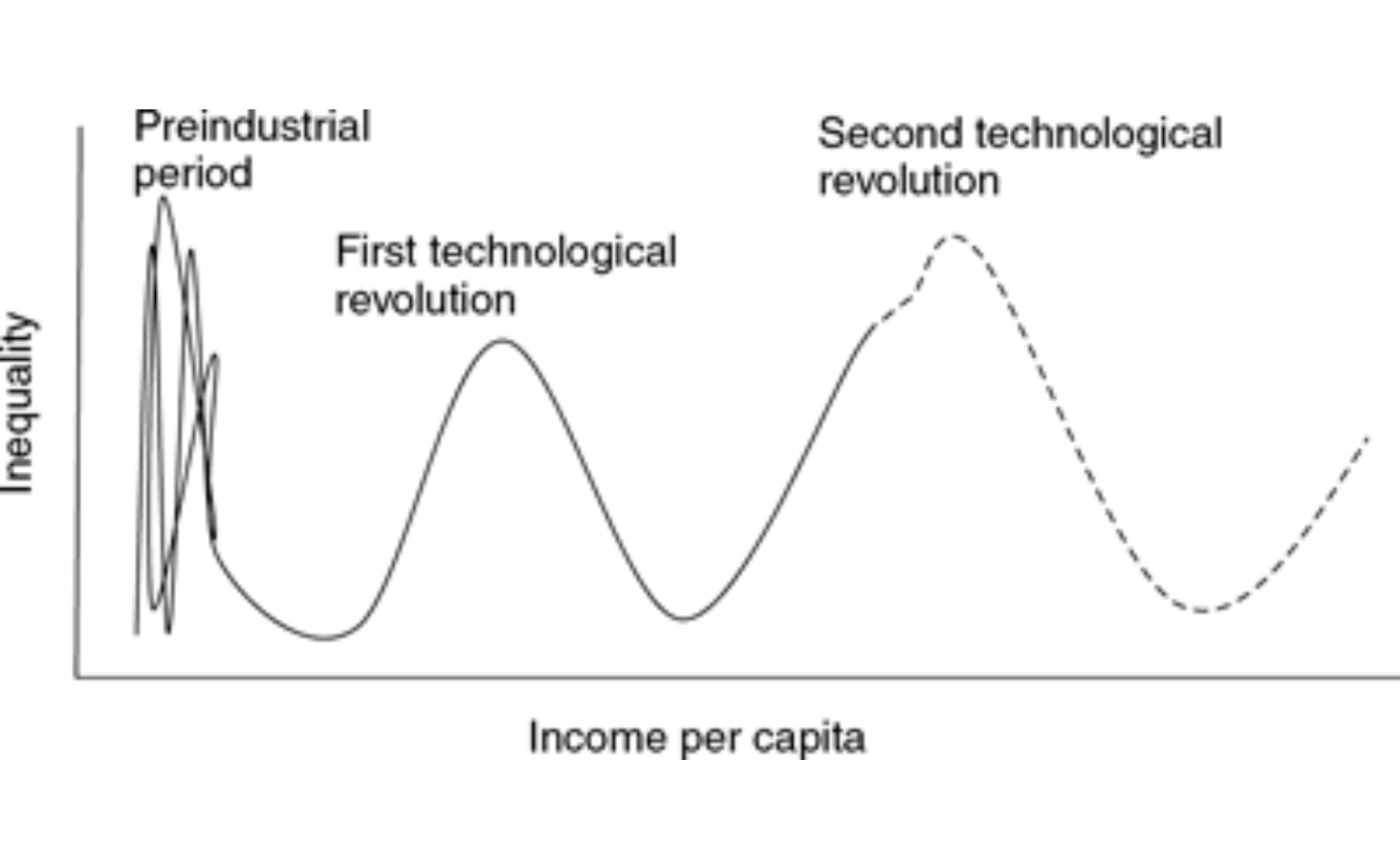

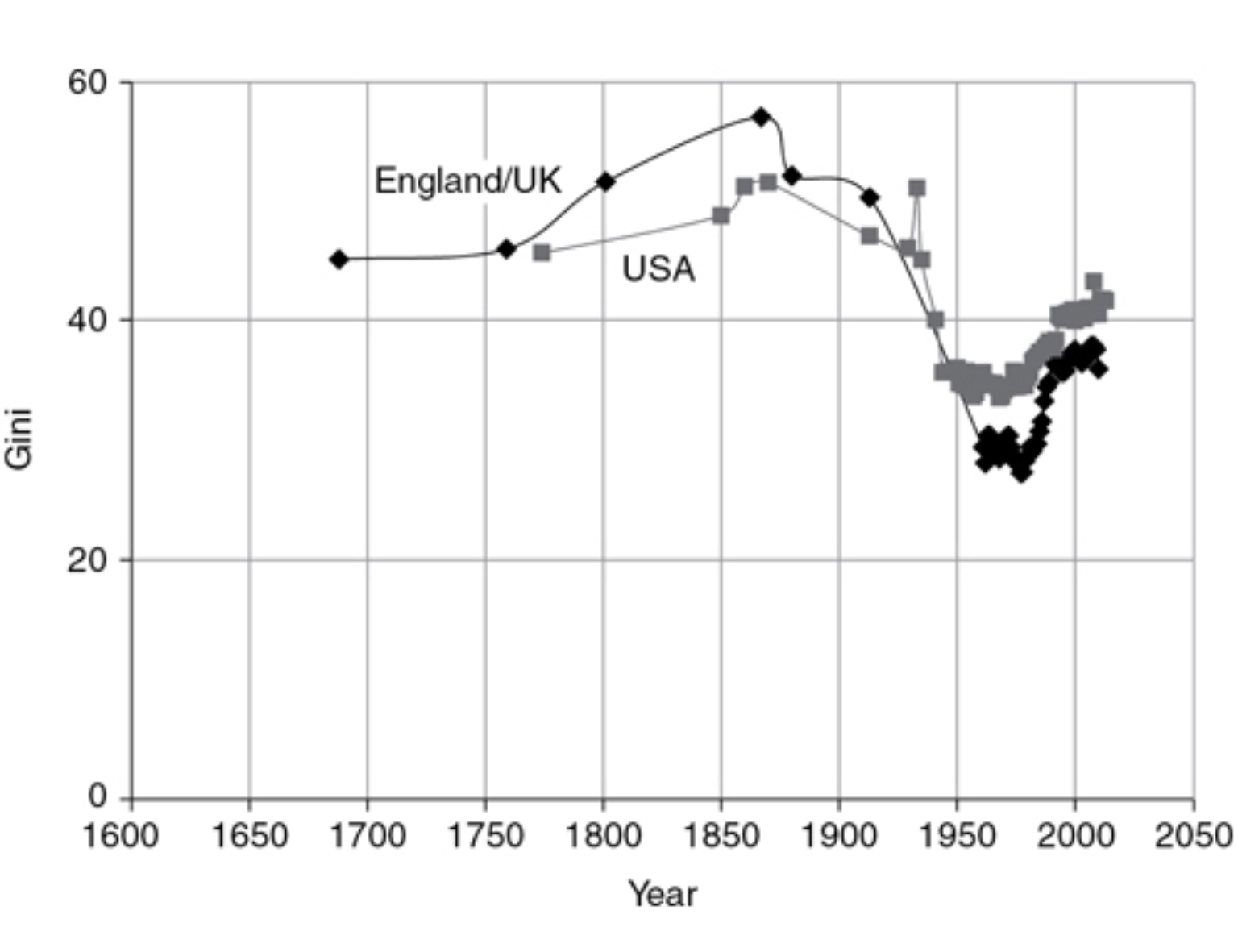

M: The Kuznets Curve was defined in the 1950s and the 1960s, which has only one curve, or what I now called one wave. Per Simon Kuznets’s definition, an agricultural society is relatively equal because, in the Kuznets’s mind, the distribution of land was relatively equal. Then with industrialization, inequality increases as people move from the countryside to urban areas where many kinds of jobs are available to the workers. Kuznets also thought that with further industrialization development, there would be greater demand for social transfers. As the mass education kicked in, educations would also become more similar among different classes. These factors reduce the difference in wages between the highly-skilled ones and those who are not. Also, Kuznets believes that rich society would settle at some low level of inequality. These are the idea of the Kuznets Curve.

The problem with is that in the last 30 years or so, there has been an increase in inequality in all rich countries. So, the problem is how to explain this situation.

Essentially, what the Kuznets Waves model does is to, first, generalize the insight that Simon Kuznets has on the technological revolution which pushes society to become more and more unequal. We are now experiencing the 2nd technological revolution with a huge transfer of labor from manufacturing industries to services. The increase in inequality is also driven by technological innovations. Like in Kuznets’s time, those who achieved certain technological developments first could make lots of money and take home the huge rent. Essentially, we now have a mechanism that is somehow similar to what we had then. This is the second Kuznets Wave in the modern era.

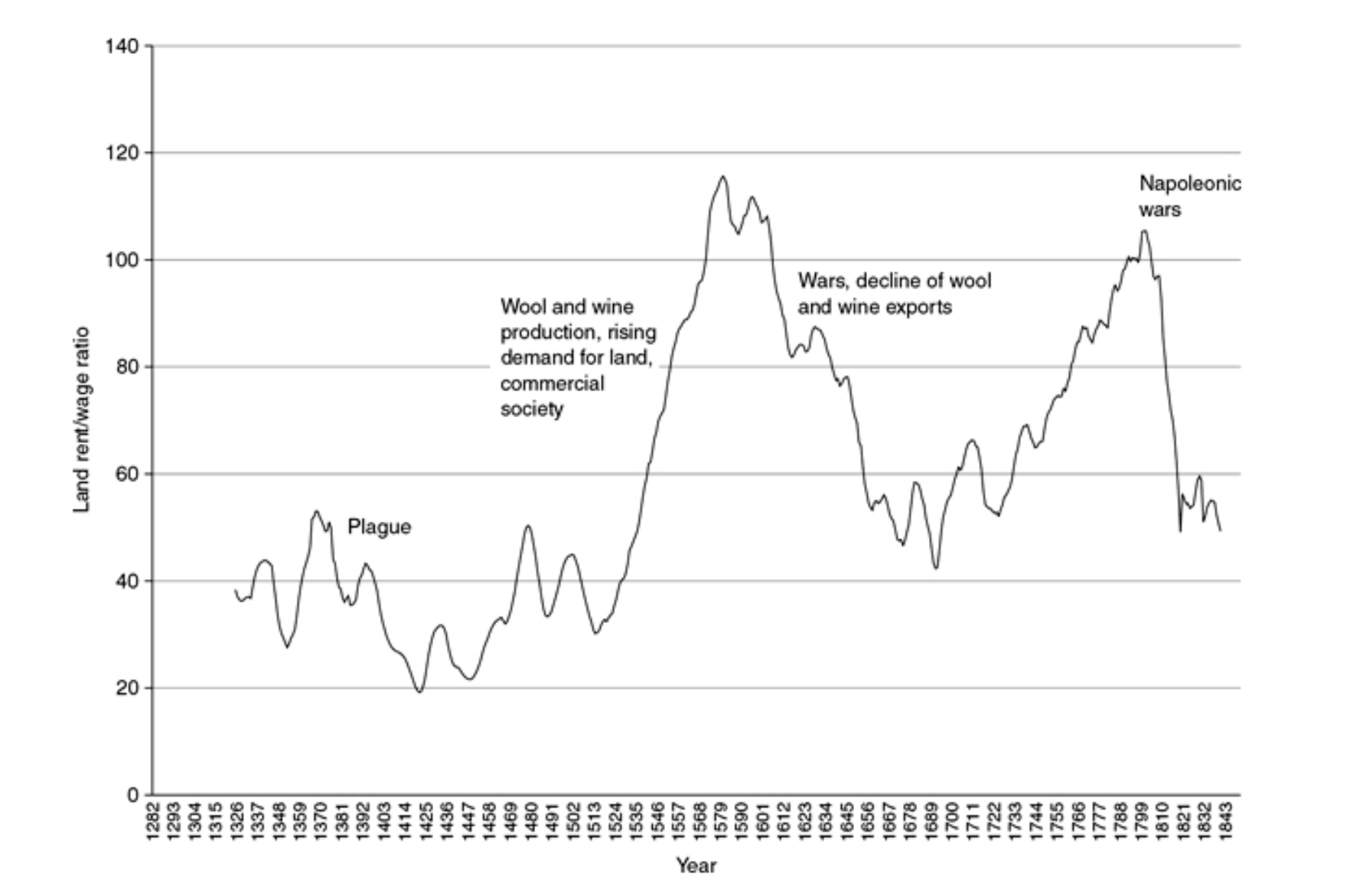

My second argument is that when we look at the developments before the industrial revolution, which we now have much more data now compared to what Kuznets had, we find similar waves of inequality. Except that in those days, as the society was stagnated, the waves of inequality were not driven by technological changes but by things like epidemics and wars.

Hence, the waves have been with us for a long time. It was just that, back then when the societies were not developing technologically and the level of income was stagnated, the forces that drove the waves in the past were essentially demographic or political, not economic. Nowadays, it is technological and economic factors that drive the waves of inequality.

Suggested Reading

Introducing Kuznets waves: How income inequality waxes and wanes over the very long run

In 1955 when Simon Kuznets wrote about the movement of inequality in rich countries (and a couple of poor ones), the US and the UK were in the midst of the most significant decrease of income inequality ever registered in history, coupled with fast growth.

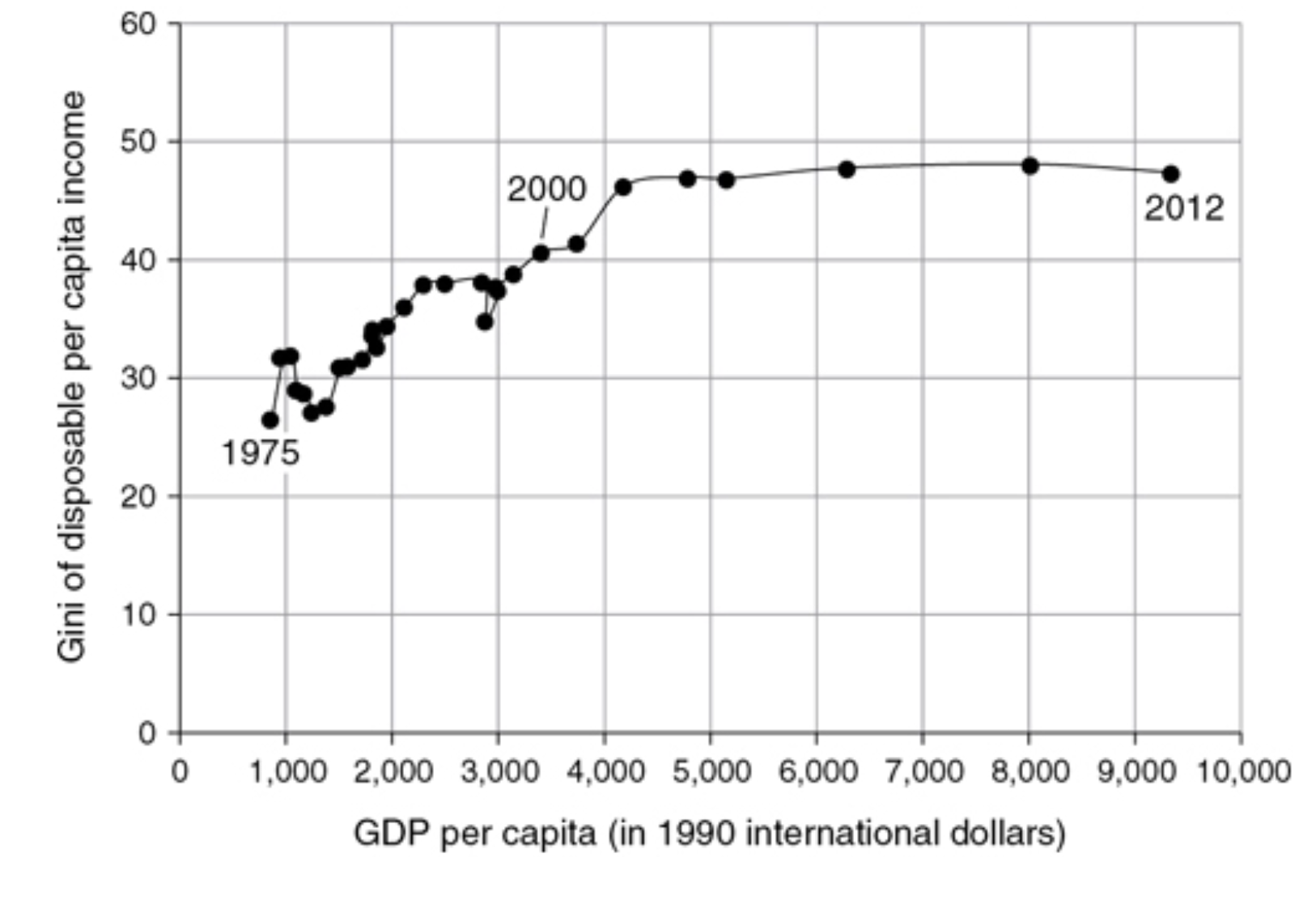

Q: When I was reading the book, I have a stupid question in my mind. Why would you use the level of income as the horizontal axis of the Kuznets Waves, just as in the Kuznets Curve? I mean, when we plot the level of inequality against the years, as a time series, we can see easily see there are the waves. Is there any reason you use level of income as the x-axis?

M: There is a reason for that. Income is used as the proxy for structural formation. In other words, income is telling us how developed the society is. Because what we have on the horizontal axis should ideally be some indicators of the structural changes in the economy and the effects of the technology, and we really don’t have that kind of general indicator, we use income as the best proxy.

One of the problems of using years on the x-axis is that, as societies don’t develop at the same rate, not only between countries the growth rate is not the same, even within a country it is not the same. Sometimes you can have ten years of near zero growth, like in Japan in recent years, for example. But in the 50s and 60s, Japan was growing at 7 to 10% a year. So if you put the time dimension in the Kuznets Waves instead, it would seem that you would expect the inequality of Japan nowadays to move in the same way as it moved back in the 50s and 60. But in reality, it does not.

Q: So income is not the perfect instrument?

M: No. If you go back to Kuznets’s idea, the perfect instrument would have been really the structural change. In those days, it would have been the movement from agriculture into manufacturing. Nowadays, we could use the share of employment going into services. But the perfect indicator should be a little broader than that because there is another structural change that is driven by the technological advancement. So, there are actually two elements that ideally you would like to have in the perfect indicator. One of them is the structural change of economy. The second one is the technological advancement.

Q: One of the important contributions of the Kuznets Waves model, in my opinion, is that it put political factors back in a dominant position in the analytical framework on inequality. Why do you think political factors are important?

M: I think the political factor is important in the model because, otherwise, we will risk going into total technological determinism.

I believe technology plays an absolutely crucial role. Technology is a very important element because it actually creates income, enables people to do new things and do more things in some different ways. It also creates new demands for labor.

On top of that, there is one element which I think is very important. It is the political element. Politics is essentially the element that comes on top of technological determinism. It actually shows that we as a society do have, in abstract terms, a free will or ability to either counteract the force of rising inequality or to actually go along with that.

Economic and technological factors are indeed dominant. In the book, I said that all the political decision-making take place within the confine of what the economic factors allow us. But there is still room for political decision-making and there is still the ability of the people to make a change. Whether in a democracy or not, there is the ability of people to claim, demand and finally, implement certain policies.

Q: Another interesting point you have put forth in the book is that you think that political factors can be modeled as endogenous to economic factors. Do you think that economic factors always come first, political factor come second?

I think if you put it like that, I would agree. I am a strong believer that economic factor, including technological development, do come first. In the Marxist terms, it is called the infrastructure. These factors limit the scope of what you can do. Unless you have an entirely voluntaristic and dictatorial government that can sort of go against the economic realities. But it is not very common.

It is more common to have governments that have adapted to the technological developments. Let me give you an example. Essentially, we don’t have much choice when it comes to the development of the information technology. There are certain governments which banned the technology, or in some cases tried to control it. But still, they are exposed to it and can’t just ignore it. It is very hard to fight against the technological developments. So, to a certain extent, the governments work within the limits set by the global level of technological development. Of course, the government can still make very different political decisions. Like we have said before, they can choose to be more acceptive of high inequality, or try to reduce inequality by adopting different means like taxation, social transfers, and better education.

Still, I would agree with you that technological and economic development may have the supremacy. Social and political development are in general responding to it.

Q: In the book, you argued that the rise in inequality in most developed countries since the 1980s is the first part of the second Kuznets Wave. Yet you also mentioned that you don’t think inequality in the US will come down soon. How should we reconcile these two arguments?

M: Let me put it like that. I have argued that the current increasing wave in the US would eventually be offset, counteracted, canceled and reversed. I have listed some forces in the book. For example, the reduction of technological rent that can be made, the political changes which we have just talked about, and the development of more pro-low-skill-biased technological innovation. But these are sort of general and hypothetical views about the forces that would offset the increase of the wave. These are the forces that I think in the medium to long term would have an impact on the rich countries.

However, in the immediate future, I think that several other forces are still working very strongly in the US. Those includes the fact that capital incomes are now heavy concentrated, that the share of capital in the total net product is going up, that more and more rich people have both high capital and labor income. These are the forces that are very strong in the short term. It leads me to believe that the turning point in the US on the Kuznets Wave is not within the horizon of the next 4 to 5 years, or not even the next 10 years. But I do believe that within the generation there will be a turning point.

However, in some other countries, for example in the UK, we have seen that the increase in inequality in the 1990s was faster than the US. In the last 15 years or so, though, UK’s inequality has been constant and we can even see a slight decline. Therefore, I think that some of the rich countries may already be at the peak or already passed the peak of the second wave. Since we have seen that the inequality in the US and the UK are often going together, I think it may be an indication of what might soon happen in the US.

Q: You have mentioned that China is on the downward sloping side of its first Kuznets wave. Why?

China is a standard example of the first Kuznets Wave. It displays most factors that we would have seen in the first wave. In the first Kuznets Wave, we should see a mass movement of population from agricultural to industry, increasing average level of education, high increase in manufacturing value added in net product and decline in agricultural value added. These are what actually happened in China. On top of those, there is the transformation of Chinese social system from essentially socialist or communist system to a de facto capitalist system. All these factors push inequality up.

Chinese inequality increased extremely fast. But when you look at the published data I had in the World Bank, you will see that there was no increase in inequality, at least the measured inequality, over the last ten years, particularly in the urban sector. That can be explained by the reduced gap between the different skilled labor. Also, the fact that they don’t have the supply of labor at the fixed wage anymore because many people have moved into the city and their standard of living has risen very significantly. The fact that there is a large increase in general education in China. Also, the fact that there is demand for social protection through extending the safety net and greater investment into the environment. All these factors were present in the US or Western Europe 40 years ago and they had led to the decline in inequality.

Plus, the demographic change that makes the Chinese population getting older. This is also the same phenomenon we have seen in currently rich countries. All these elements lead me to believe that there are very strong imputed forces that, for the next generation or so, they would push Chinese inequality down.

However, inequality is such a complex phenomenon, if you have ten different forces that are pushing it, it is not likely that all of them would be moving in the same direction. In the case of China, two forces would have the opposite effect. One of them is the rising share of income from capital in China. Like in many other countries, it is heavily concentrated among the rich.

The second element, which is difficult to quantify, is the extent of corruption. We can’t really quantify that. Still, we do believe that corruption is generally more common for those who already have more money than those who are poor. This increases inequality.

To summarize, I would say the US being close to the peak of the second wave but still possibly become increasingly unequal for the next 5 years or so. I think that China is at the very peak of the first wave and becoming more equal in the future.

Q: However, you also think that the development in China, namely the reduction of inequality, will likely raise the global inequality level. Why?

M: The reason is that at some point, which is practically now, the mean income of China would be at about the level of the world’s average. From that point on, as you created distances between yourself, which is China in this case, and other countries that are way below you, like Vietnam, Indonesia, Congo, Sudan, Nigeria, you start contributing to global inequality.

In the past, China, by being relatively poor and by becoming richer, has actually made global inequality smaller. Now China is losing that element because it became quite rich. The further it goes the more it will contribute to global inequality. Now its contribution is still not that much because the gap between the world’s average income and China’s income is relatively small. Maybe in 10 to 15 years, when China’s income is at the level of the medium income level in the EU, China will contribute a lot more to the global inequality.

It is simply the fact that China has been very successful and becoming rich that means that, to reduce global inequality, we need to have countries that are below China, India for example, to grow very fast. That’s how the mechanic of global inequality works.

Discussion continued in part two, where Prof. Milanovic will discuss whether he thinks the study of inequality should be considered part of macroeconomics.

“Is Inequality part of Macroeconomics?” Branko Milanovic explains | #WITGT21 Interview Series |

In part two of our interview, Prof. Milanovic discusses whether he thinks the study of inequality should be considered part of macroeconomics. Also, we explored if it is possible to combine the Kuznets Waves into macroeconomics models.

Independent Economics Journalism

Stay ahead of the curve — follow EconReporter for in-depth coverage on economics & markets.