Last Updated:

Welcome to the latest installment of our interview series “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?” and part two of our interview with Branko Milanovic, Visiting Presidential Professor at the Graduate Center of City University of New York.

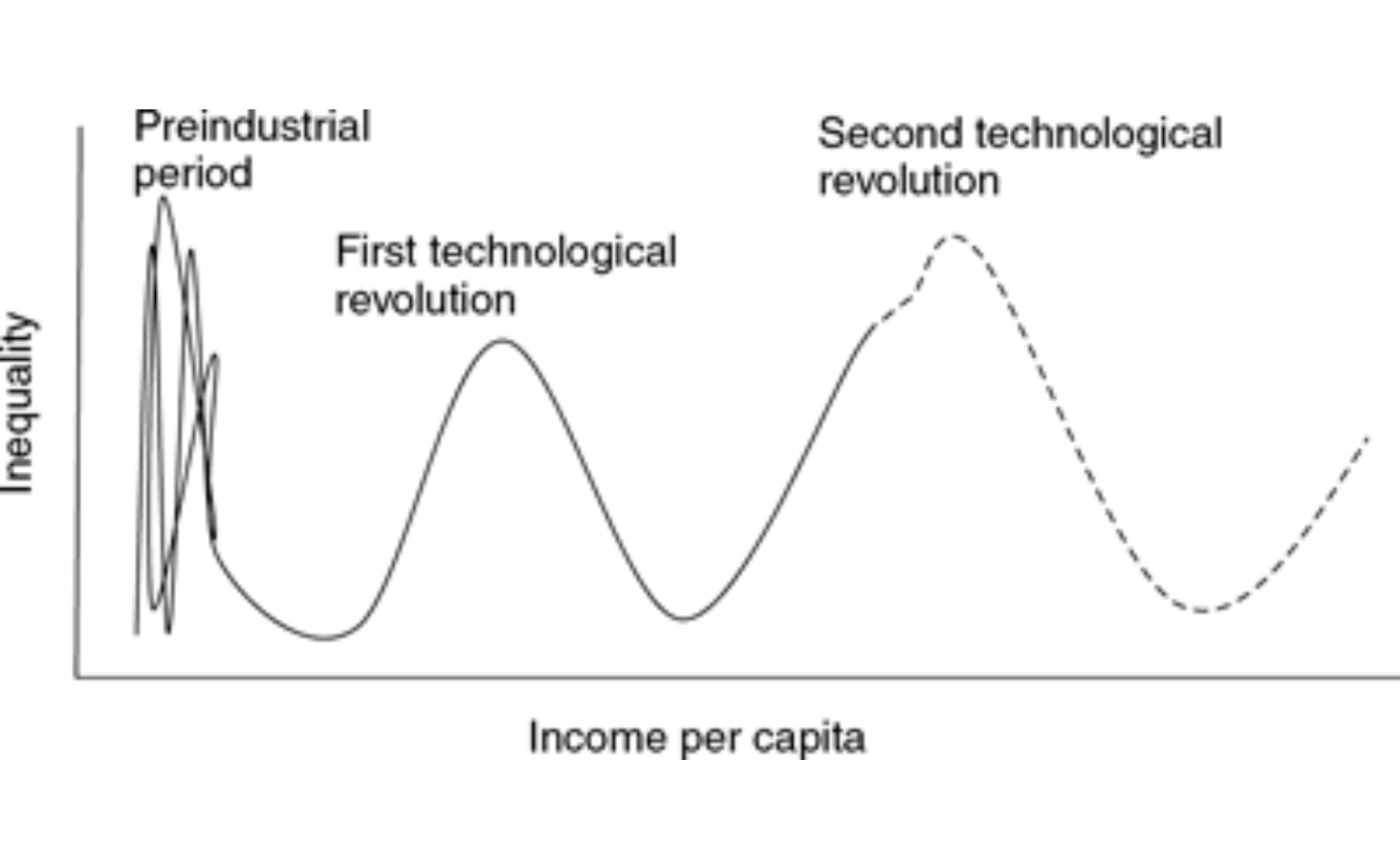

In the first part of the interview, Prof. Milanovic talked about his latest book “Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization” and how to use his new idea, the Kuznets Wave, to understand the developments of global inequality.

In part two of our interview, Prof. Milanovic discusses whether he thinks the study of inequality should be considered part of macroeconomics. Also, we explored if it is possible to combine the Kuznets Waves into macroeconomics models. (The interview is edited for clarity. All mistakes are ours.)

Q: EconReporter M: Branko Milanovic

Q: Do you consider inequality research as a subject of macroeconomics? Do you think that inequality should have any implications for the developments of macroeconomics theory and policy?

M: It is a very important and interesting question. Let me put it like this. Historically, since the neoclassical economics won very strongly in the US since the 1940s, the study of inequality has been relegated to footnotes essentially.

There is an ideological reason for that. It was always considered not politically desirable to study inequality too much because people want to focus on growth. If you study inequality, somehow it seems that you are arguing for redistribution of income. Obviously, this is not true because you can study inequality like Pareto did, who was the most right-wing economists you can imagine but at the same time he was the originator of the study of interpersonal inequality. But people don’t think in such a sophisticated way. They just say “Well, you are studying inequality. It must be because you are envious and want to take income from me!”

Still, this was not the main reason. The main reason was the structure of general equilibrium. You essentially have the situation in which all prices, including the prices of capital, labor and other factors of production, are determined in the general equilibrium. The prices are considered “right and fair”. In other words, that essentially mean that we don’t have to ask what is the price of labor because we already know that the economic system would deliver the “right” price of labor. That essentially eliminated from the theory the study of the returns to labor or capital.

On top of that, economists would say that the Walrasian General Equilibrium does not really deal with endowments. The endowments are something that we don’t discuss because we just take note of the endowments individuals bring to the market, as it is a “given”, and how the price is determined. How you got this endowment is not part of the general equilibrium discussion, or often of an economic discussion at all.

That basically eliminate the two important elements in the study of inequality. It eliminated the question on how I acquire my wealth or my educations. It also eliminated how the pricing of my education and the capital was made. That’s the reason why income inequality was really left totally outside of mainstream neoclassical economics.

I remember when I was writing my first articles on inequality some 25 years ago, I could not find the term in JEL (Journal of Economic Literaure) codification. There was no term which you could actually attach your work to. You could put it in “Welfare”, for example. There are also “Educations” and “Health”. But we didn’t have “Income Distributions”. Later they introduced “Income Distributions” but the word “Inequality” is still not there. There is still a resistance to study that.

After all the fuss re wealth and income inequality,JEL classification has the term inequality appearing three times, none of which relevant pic.twitter.com/s8fajDGeCH

— Branko Milanovic (@BrankoMilan) February 14, 2017

@noralustig I remember when writing a paper on ineq of income you needed to combine JEL terms like "welfare", "distribution", "wages" etc.

— Branko Milanovic (@BrankoMilan) February 14, 2017

@BrankoMilan Background Jul 2011 Lustig wrote JEL finally included income distribution in codes. Thank Deaton. I asked him and he got it.

— Nora Lustig (@noralustig) February 14, 2017

🚨Advertisement🚨

Now people are starting to write the textbooks in inequality. Yet, so far, we still haven’t had them. We have a lot of knowledge on inequality but they are disbursed. Some of them are in Labor Economics, some are in Trade Economics, and some are in Economics of Development. For example, students learn the Gini Coefficient and the Lorenz Curve in Economics of Development, as if it only applies to poor countries and rich countries don’t have the problem of income inequality.

These are the two elements that make inequality a footnote essentially. One is the pure political desire not to study income inequality. Another one is ideological, which is the way that neoclassical economics look at and solve the economic problem.

To your question, I am not sure where inequality would be put exactly because the elements in the field that are both micro and macro. Some elements are micro. For example, now there are huge studies of income based on individual household survey or fiscal data. We now have huge databases on inequality and use sophisticated econometric to study it. So in this sense, it is very much micro.

But then there is an obvious linkage between those micro analyses and the effect that inequalities have on the macro variables like GDP growth, government spending, even inflation. This became very clear during the crisis.

So, I think inequality is actually between the two. I am not sure where it would be located but I could see that the original work can be done in micro and in econometrics. Then the implications of certain inequality changes have to be studied in macro, as one of the macro variables.

Q: Do you think your Kuznets Waves model can have some implications or applications in macroeconomics research?

M: I am not quite sure really. To tell you the truth, I haven’t thought of that.

I see your point. The Kuznets Waves could be combined with either the cyclical models of the development, of the GDP per capita, of the industrial production and so on; or the Kuznets Waves can be put into a general macro framework.

It could be in an entirely macro framework because you can just take one variable, say, the income inequality measured by the Gini or something else, and put it either into a regression or a model of the whole economy. But of course, that would only be the macro part of the work. You will still have to work on the micro part, which is the data behind that inequality measure. There could be like millions of individuals and their incomes data, among many things else.

I haven’t really thought of the direct application of the Kuznets Wave in the macro models. It is an interesting question. Here is an example of how to combine the Kuznets Waves and macro models, which I am just thinking out loud right now. First, we model the movement of inequality in terms of Kuznets Waves. Then, for example, we model that the rising inequality leads to either excessive borrowing by those who don’t benefit from rising income so that they can sort of have a feeling that they are keeping up with the rich people; or, leads to lower consumptions because people with higher income has lower marginal propensity to consume. Then we can sort of model the effects of the Kuznets Wave on the macroeconomy, either because there is an insufficient demand that would slow down the growth rate; or, excessive borrowings create a sort of bubble system that we have seen, for example, in 2007. In this way, The Kuznets Waves model does lend itself to the macro modeling framework.

Q: In the last chapter of your book, you have suggested that economists should reconsider the issue of “methodological nationalism”. Why should inequality study be more, say, “globalized” instead of focusing on national data?

M: We have been hostages of what is called “methodological nationalism” because most of our data in economics are produced in national level. The natural framework is the nation-state because our research depends on data produced by national statistics offices or national surveys of finance, wealth or income.

That’s not a bad framework. But it is too constraining for the analysis certain issues, including global inequality and global poverty. It is also obviously too constraining for the analysis of the epidemic, climate change, migrations or tax heavens, among others. Certain things cannot be only studied at the national level because the impact to those things is global.

In the subject of global inequality, the best example is migration. Migration can only be perceived as a worldwide phenomenon. It is the result of globalization. It happens because, for example, people have information of living standard in rich countries and people also have the reasonably cheap transportations to get there. Plus, it takes place under the condition that the gain for migrations is huge, which means that there are huge differences in mean income between different countries.

So, we need to address migration as a global phenomenon, or at least at the regional level. For example, I think Europe is starting to address the migration between Africa and Europe as a regional issue. It is not just an issue between France and Monaco. It is an issue between EU and most of the African countries.

I often tell my students, if you move from methodological nationalism to global perspective, it is a little bit like you move from a 2D world to a 3D world. There are many things that you would never have thought about and you will only see them at the global level.

Another good example is that when we think of inequality of opportunities, we generally speak about that only in the framework of a nation-state. We say poor people, women or people of different races don’t have the same opportunities. In fact, the same argument exists at the global level. We have people with the same effort and same education level earning very different income level, simply because some were born in poor countries and some were born in rich countries.

If you think the world as one, fundamentally it is not very different from the situation that a person who is born in a rich family having a different income when compared to an identical person that is born in a poor family. Within nation-state, we don’t find it desirable nor acceptable. But in the global framework, we do.

We should ask ourselves: Should we accept this kind of inequality of opportunities? Should our concern with inequality of opportunity ends in the national border or not? I think these are very important questions. Maybe we can say: “Of course we are not concerned with global inequality of opportunities.” There are some good reasons that John Rawls has put forth. But these are the issues that we would never have thought, had we not actually looked at the world as a whole.

Photo credit: Oxford Martin School Youtube

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡