In early May, the Hong Kong financial system saw a massive inflow of capital amid the so-called “Asian Financial Crisis in reverse.” This was reportedly triggered by a 10% surge in the Taiwan dollar’s exchange rate against the USD amid worries that the Taiwanese government might have to agree to currency depreciation as part of trade negotiations with the US.

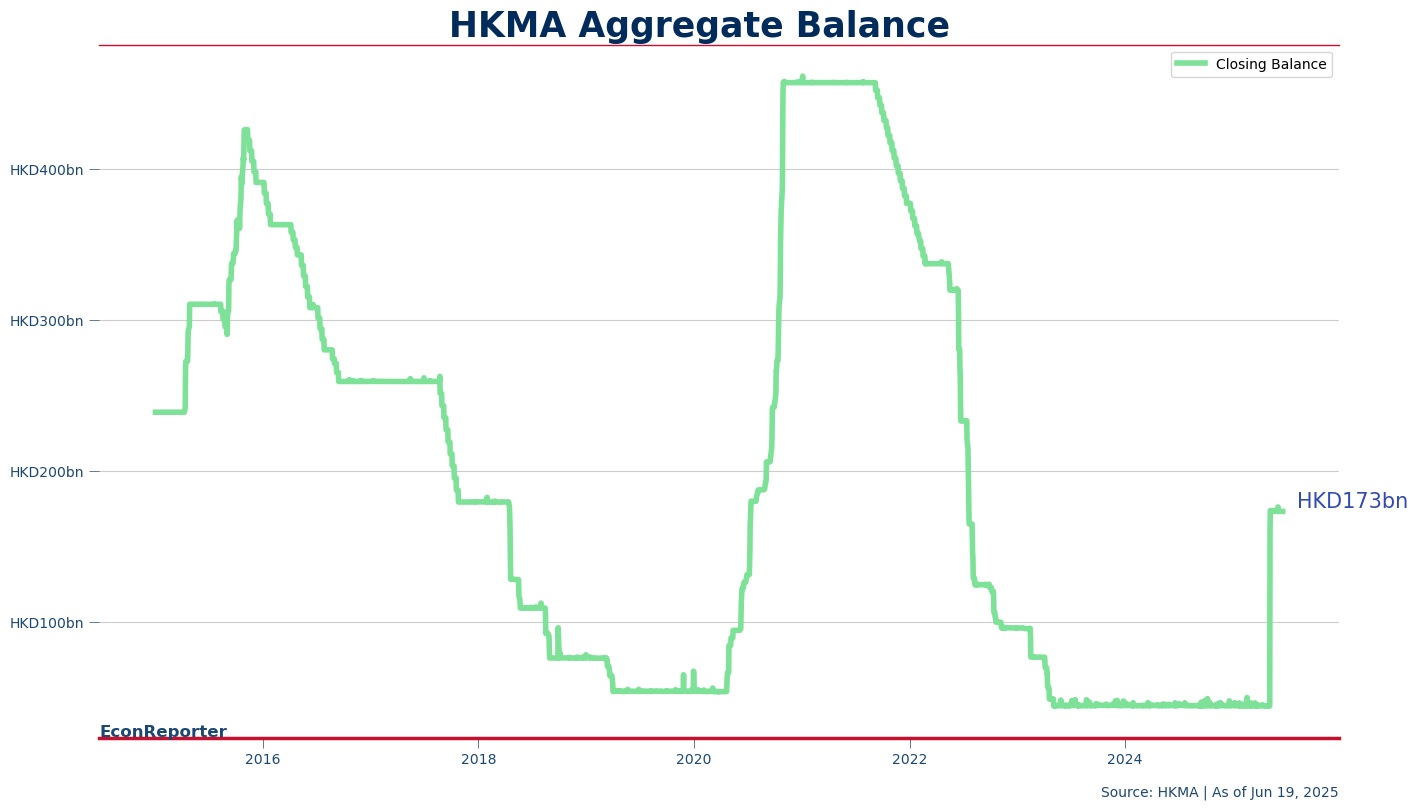

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) had to intervene in the foreign exchange market, selling HKD 129 billion to the Hong Kong banking system in two days to defend its Linked Exchange Rate System. This HKD injection was unprecedented in scale, flooding the Aggregate Balance with significant liquidity and raising the level from just above HKD 40 billion to over HKD 178 billion.

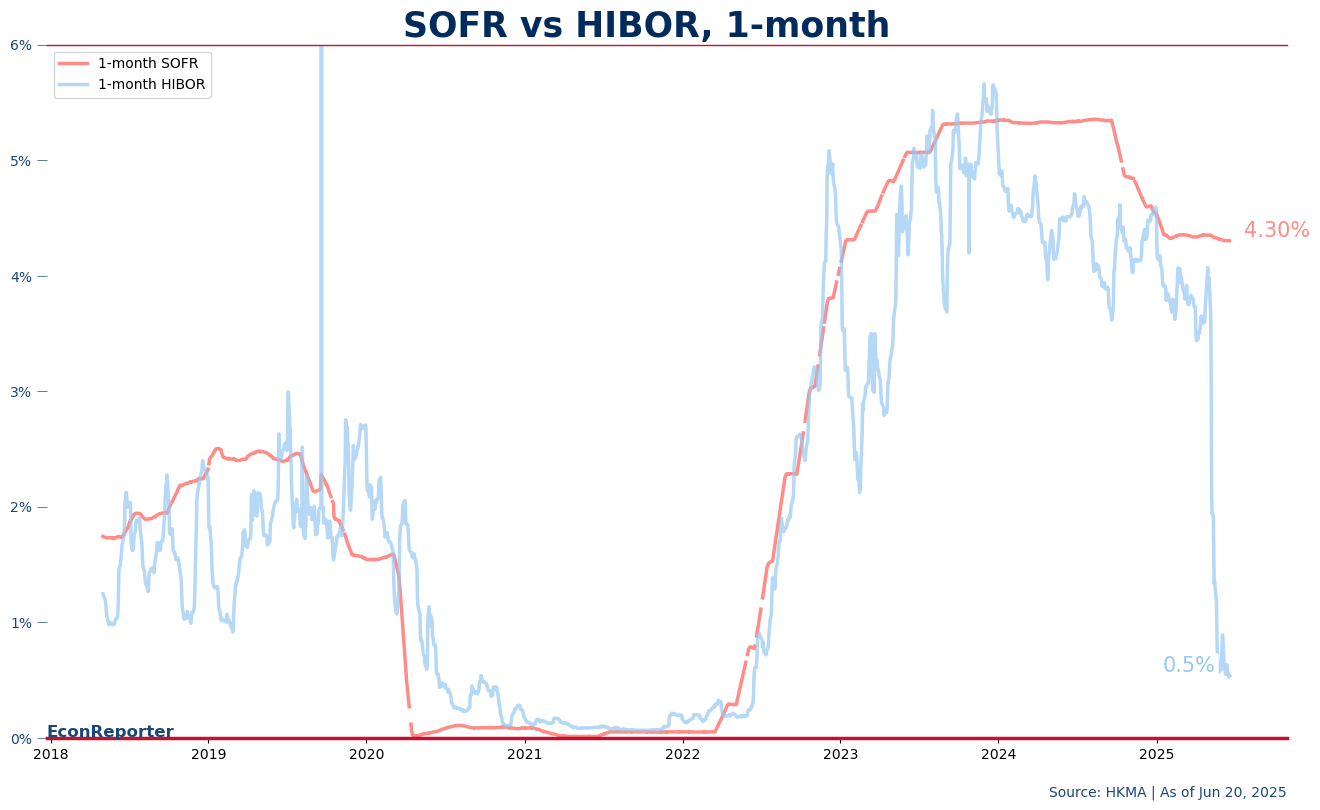

The Aggregate Balance is the sum of all clearing accounts that banks in Hong Kong hold with the HKMA and is often interpreted as an indicator of interbank liquidity. With the Aggregate Balance more than quadrupling, Hong Kong’s interbank lending rate dropped towards zero. For example, the one-month Hong Kong Interbank Offered Rate (HIBOR) was around 4% before the massive capital inflow but has since dropped to just 0.5%. For comparison, the 30-day SOFR is around 4.3%.

A core feature of Hong Kong’s currency board system is interest rate arbitrage. If comparable interest rates in Hong Kong and the US diverge, market participants should engage in arbitrage and compete away the interest rate spread. Hence, it is interesting to observe that a spread of over 3.5 percentage points can persist for close to two months and that arbitrage has failed to close the gap.

Is the Dollar Peg Failing?

For example, Bloomberg Opinion’s Shuli Ren said, “[t]he fact that this rate gap has not narrowed shows there’s little appetite to earn dollar carry trades.” She argued that such a persistent interest rate spread shows “the city has practically moved on from a waning reserve currency (the USD), tearing itself from an interest rate trajectory mapped out by central bankers thousands of miles away. This peg is too archaic.”

Whenever a “glitch” is observed in the Linked Exchange Rate System, commentators commonly jump to discussions of whether the currency peg is still suitable for the Hong Kong economy, which is a worthy topic to ponder. But it is often too quick to ignore the technical aspects behind the persistence of these interest rate spreads and too fast to conclude the currency peg is “doomed.” This article, however, will explore some technical factors behind this interesting interest rate gap.

A critical piece of context is the Federal Reserve’s policy shift towards interest rate control since the beginning of the quantitative easing (QE) era. The US central bank adopted the so-called Floor System, which involves substantially increasing the reserve supply and using the interest on reserve balances (IORB) as a “floor” to guide the short-term interest rate to its policy rate range.

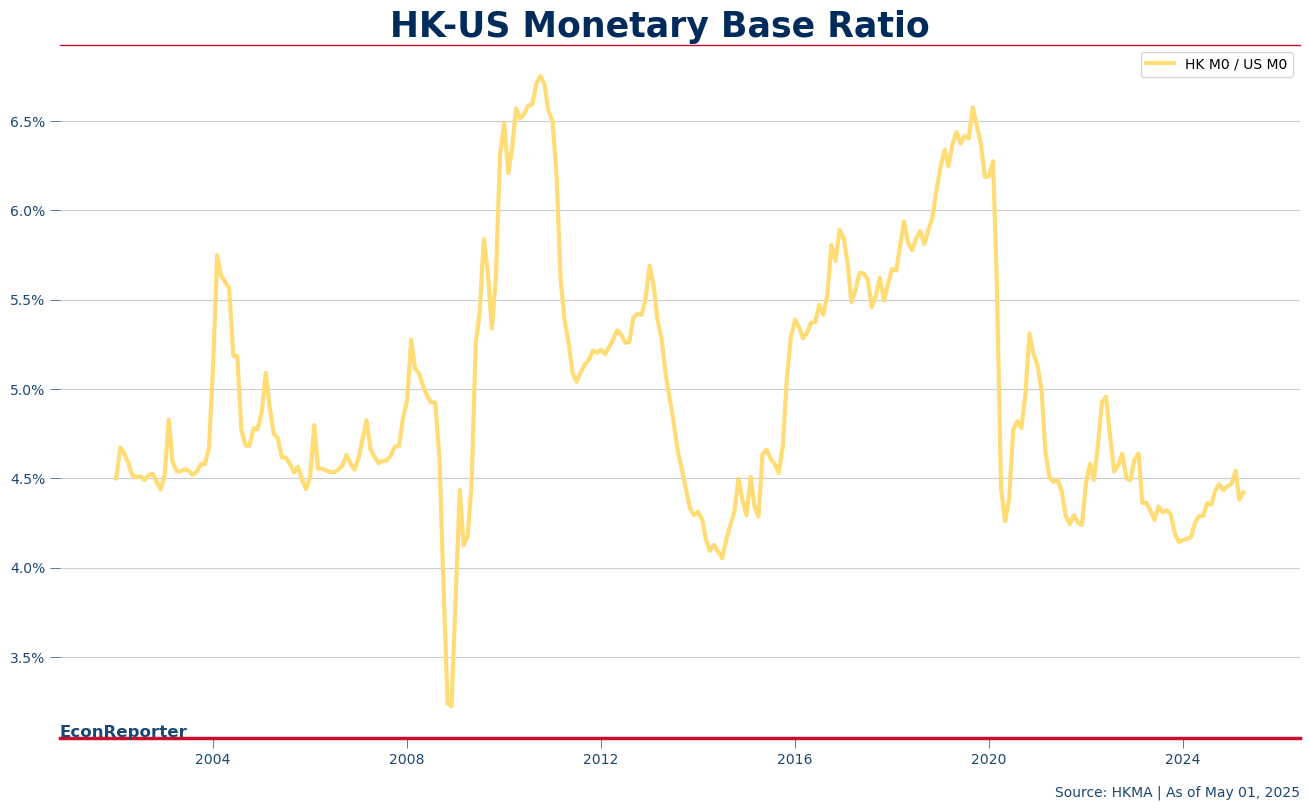

As a result of QE, the monetary base in the US grew almost seven-fold, from around USD 840 billion at the start of 2008 to over USD 5.7 trillion in May 2025.

What about Hong Kong? Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, the city’s M0 increased on a similar scale, from HKD 339 billion at the beginning of 2008 to nearly HKD 2 trillion this April—a nearly six-fold increase.

If we divide HKD M0 by USD M0, we can see a fluctuating yet, on average, relatively stable ratio of around 5%. In general, the monetary base for the HKD grew in proportion to that of the USD, even with the radical change in the US monetary policy regime.

This then raises a question: If the Fed needed to install an interest rate floor to guide its interest rate in the age of abundant liquidity, how can Hong Kong’s de facto central bank, the HKMA, ensure its interest rates follow the movements of their US counterpart?

Splitting the Liquidity Pool in Two: The Aggregate Balance and Exchange Fund Bills and Notes (EFBNs)

That was not a problem in the first half of the 2010s, as the global economy was still in its post-2008 recovery and interest rates were mostly zero or negative in advanced economies. But when the Fed attempted to raise interest rates and begin quantitative tightening (QT) to remove excess liquidity from the market in the latter part of the 2010s, this became an issue.

When the Aggregate Balance is flooded with liquidity, banks generally have less incentive to borrow from each other. This tends to push the interbank interest rate, HIBOR, towards zero. Moreover, HIBOR is likely to be less sensitive to changes in liquidity supply in the Aggregate Balance, meaning a much larger capital outflow is needed to move HKD short-term rates.

As the Fed raises interest rates, the orthodox narrative suggests that the interest rate spread between the US and Hong Kong would create a profit opportunity for carry trades; investors would borrow from the low-cost HKD and invest in the higher-yield USD to gain from the interest rate spread. This process should induce a capital outflow from the HKD and drain the Aggregate Balance, eventually raising HIBOR to a comparable level with its US counterpart.

Well, the Aggregate Balance did experience a downward cycle around 2016. However, the HKMA did not have to intervene to sell USD to the banks (the flipside of banks selling HKD to the HKMA) until April 2018. The HKD monetary base also increased between 2016 and 2018 (which resulted in an observable bump in the HKD-USD M0 ratio graph above). So the traditional narrative only partially explains the situation. What is missing from this picture?

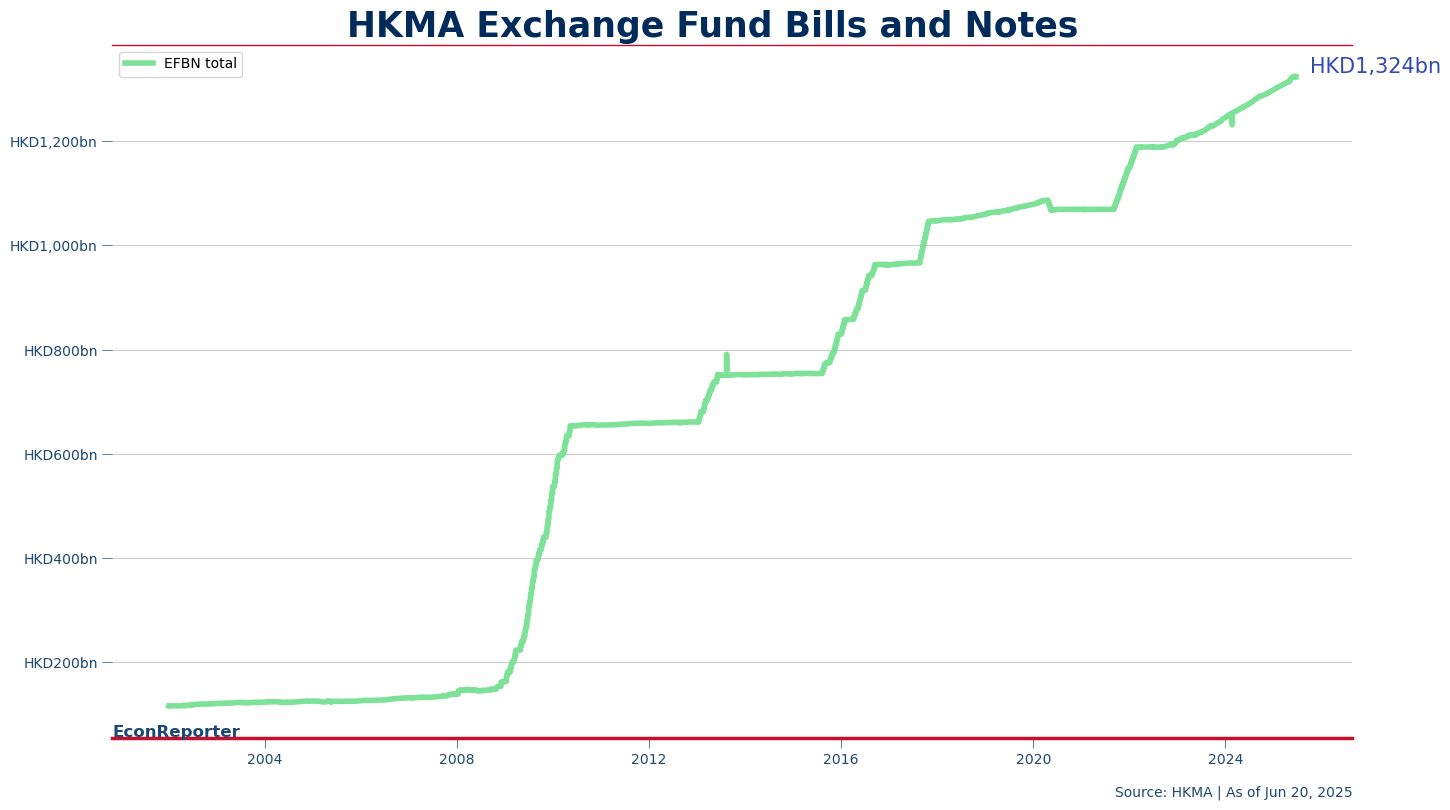

The missing part is the Exchange Fund Bills and Notes (EFBNs). EFBNs are HKMA-issued HKD debt securities backed by USD exchange reserves; thus, they are counted as part of the HKD monetary base. These debts are mostly held by banks in Hong Kong, which can use them as collateral to conduct intra-day repo transactions with the HKMA and to borrow overnight liquidity from the de facto central bank’s discount window.

Since the Fed engaged in QE, the HKMA has issued a large volume of EFBNs. The total amount of EFBNs outstanding was less than HKD 200 billion at the start of 2008; today, there are over HKD 1.3 trillion of EFBNs in the Hong Kong financial system.

In the Hong Kong Linked Exchange Rate System, EFBNs served as an alternative form of liquidity storage for banks in Hong Kong. They have a choice holding liquidity in form of deposit with HKMA in the Aggregate Balance or in form of EFBNs.

Whenever a new EFBN is issued to a bank, the HKMA withdraws an equivalent amount of HKD from the bank’s clearing account, reducing the Aggregate Balance by the same amount. So, in effect, the HKMA can absorb “excessive” liquidity from Aggregate Balance with additional issuance of EFBNs. And, the amount held in Aggregate Balance would directly affect HIBOR levels.

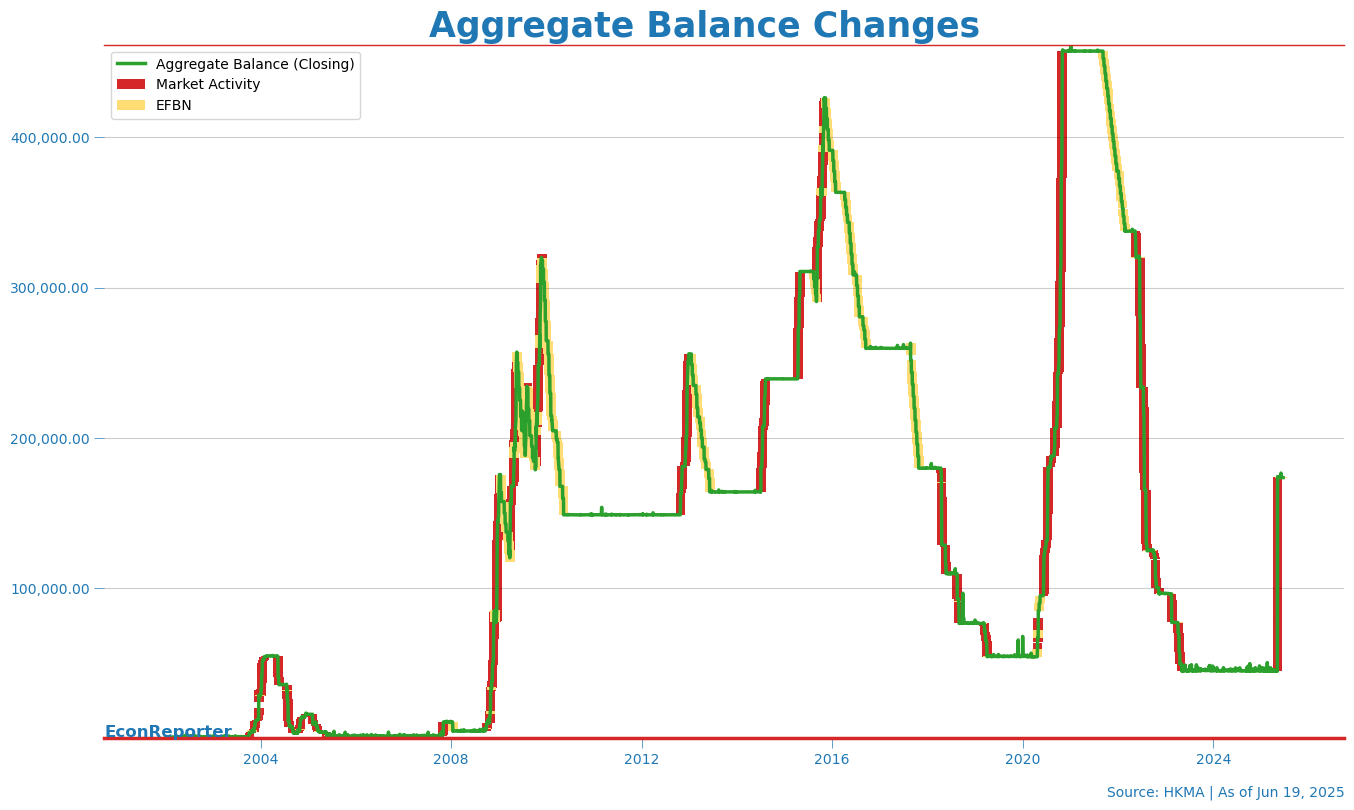

In the graph below, we analyze the changes in Aggregate Balance in terms of two major drivers—inflow and outflow generated by HKMA interventions (market activity, highlighted red, in the graph) and additional and reduction in issuance of EFBNs (highlighted yellow in the graph).

As is evident from the graph, increases in the Aggregate Balance are mostly the result of USD inflows, while decreases are consistently initiated by the HKMA issuing more EFBNs. It is also notable that in the last two Fed rate hike cycles, the changes in the Aggregate Balance were first started by additional EFBN issuance, before capital outflows kicked in at a later stage.

A potential interpretation of the post-2008 Aggregate Balance development is that the HKMA can and did intervene to halt an “excessive” buildup of liquidity in banks’ clearing accounts. These additional EFBN issuances helped absorb liquidity from the Aggregate Balance and ensured interbank lending activity remained responsive, allowing HIBOR to rise in step with US rates.

Will HKMA ‘intervene’ this time?

This raises the question of whether the HKMA needs to issue an extra amount of EFBNs to help nudge HIBOR back into alignment with SOFR. Technically, the HKMA can do it this way, but so far it has refrained from using such tactics.

First of all, the HKMA’s official stance has always been that it “doesn’t have an interest rate policy” and it will not adjust EFBN issuance to “target Hong Kong dollar interest rates at certain levels.”

Second, the current Aggregate Balance level is not considered elevated compared to recent experience; a simple reading of the graph above would find that the current Aggregate Balance is close to the level where HKMA usually stopped additional EFBN issuance and let market activities take control. This may suggest the current Aggregate Balance level is not far from its interest rate sensitive region and hence HKMA may have limited appetite to use EFBNs as an “intervention” tool.

Moreover, a lower interest rate environment can potentially provide some temporary relief to Hong Kong’s weakening local economy, for example, through lower mortgage payments, which are usually based on a variable rate tied to the one-month HIBOR. The current interest rate divergence may not be unwelcome for the HKMA at this moment, as long as the currency peg’s credibility is not affected.

HKMA Chief Executive Eddie Yue said last month: “If Hong Kong dollar supply continues to exceed demand, market forces in the form of carry trades would drive the exchange rate lower, and interbank rates will go higher perhaps to once again approaching levels close to their US dollar counterparts. Yet, it is highly uncertain how long and at what pace this process will take.” This suggests the HKMA is not in a hurry to bring HKD interest rates back up to the level of USD rates. Ultimately, the persistence of the interest rate spread may be less a sign of the peg’s failure and more a conundrum underpinning HKMA’s modern liquidity management in an era of abundant reserves.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡