Last Updated:

This article is the first installment of “Economics can help (Covid-crisis edition)“, an interview series about how economics can help in the Covid-crisis, and what economists have learned from it. You can subscribe to the series on Substack to get future updates.

You can also read in Substack ad-free (the auto-placement of the ads are really aggressive here)

An edited transcript of the interview can be found here.

“The US has not brought this pandemic under control,” Nobel winning economist Paul Romer said, “the economy is in a depressed state because people are afraid of returning to their normal activities.” He worries that the Covid-crisis is showing signs of failure in the US — not only is the government not leading, but the intellectuals also failed to advise.

In an exclusive interview with EconReporter on Tuesday, Romer, co-recipient of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics Science, urged the US to adopt large-scale testing immediately to halt this most detrimental economic slump ever since the Great Depression in the 1930s.

Scale up testing. Solve the crisis!

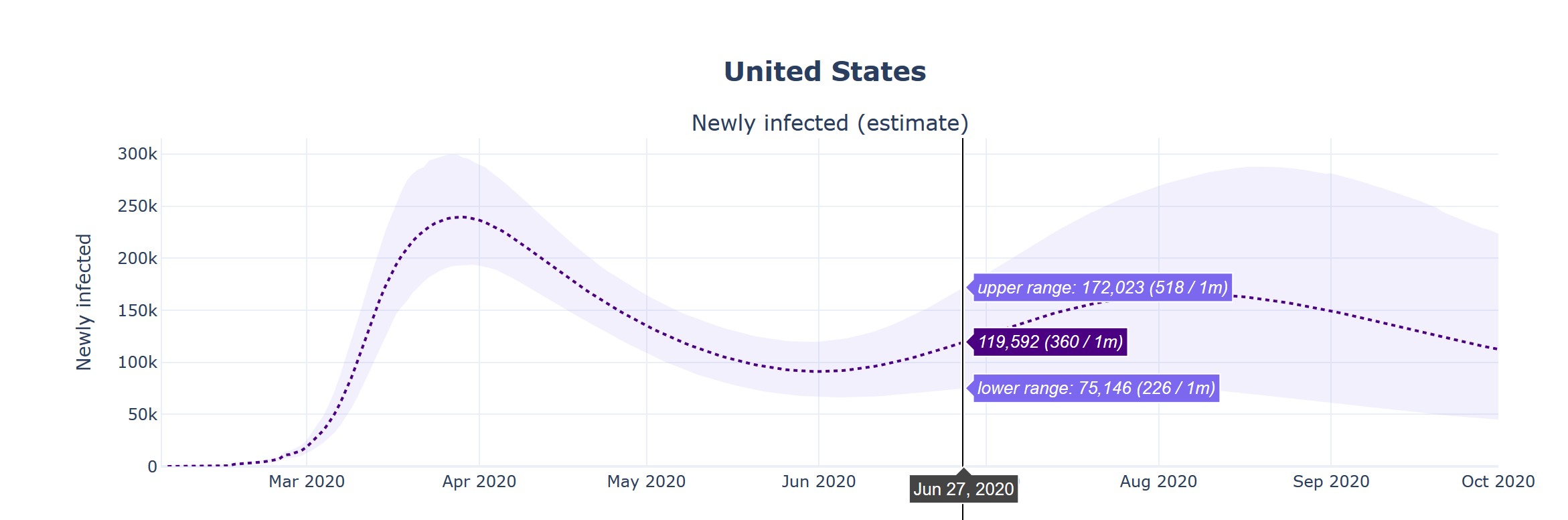

“Even before the recent upturn, it is estimated that about 100,000 people get infected each day,”

The 100,000 daily infection figure Romer cited is from the epidemiological models on covid19-projections.com, which uses artificial intelligence to forecast infections and deaths from the COVID-19 pandemic.

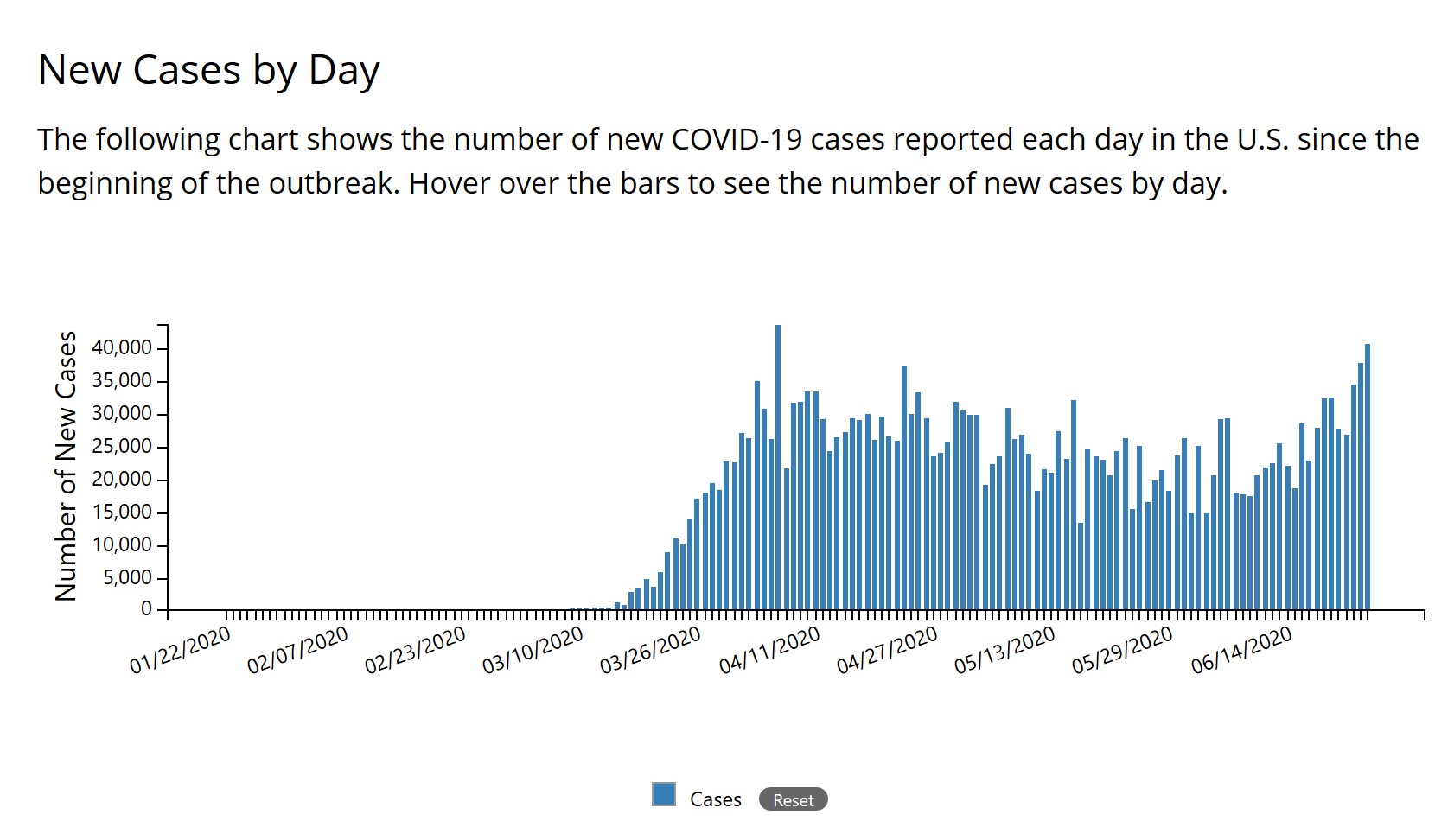

The CDC reported 40,588 daily new cases on Friday, but as such “confirmed cases” figure is limited by the number of Covid-19 tests conducted each day, it is unlikely to reflect the full picture of how the virus is currently spreading in the country, compared to model-based estimates.

The CDC reported 40,588 daily new cases on Friday, but as such “confirmed cases” figure is limited by the number of Covid-19 tests conducted each day, it is unlikely to reflect the full picture of how the virus is currently spreading in the country, compared to model-based estimates.

The US is likely still facing months of high level of infections, and “people are nervous about going back to many types of activities — jobs or some patterns they followed at the beginning of the pandemic– because they don’t want to take the chance to be one of those 100,000 that get infected each day,” Romer said.

The US is likely still facing months of high level of infections, and “people are nervous about going back to many types of activities — jobs or some patterns they followed at the beginning of the pandemic– because they don’t want to take the chance to be one of those 100,000 that get infected each day,” Romer said.

The NYU economics professor published “Roadmap to Responsibly Reopen America” in late April, a 10-page proposal on how to reignite the US economy before the vaccines for the coronavirus are invented. The method is simple — test everybody and isolate those who are infected. “If we know who those infected people are, we can isolate them and stop new infections, and the pandemic will ease. It’s as simple as that!” said Romer.

In the proposal, he suggested that the US should test everybody every two weeks, translating into about 25 million tests per day, on an ongoing basis. By identifying the infected and separating them from the healthy population until they recovered, this can instill confidence in people to perform their usual economic activities.

Two months on, the daily tests performed in the US increased to around 500,000 per day, from around 150,000 daily in April; it’s still far off Romer’s advocated target.

Is 2.5 million tests a day still the target? Romer replied, “No, I think we need much more than that.”

Wuhan, once the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic in China, offered an example that scaling up testing rapidly is feasible. Late last month, the Chinese government tested 9.9 million people in the province in 14 days, at a cost of about USD 13 per person tested.

“Suppose it costs USD 20 to test each person in the US, to test 330 million people, that costs about USD 7 billion.” In comparison, the pandemic might cost the US economy about USD 8 trillion if it continues the current path.

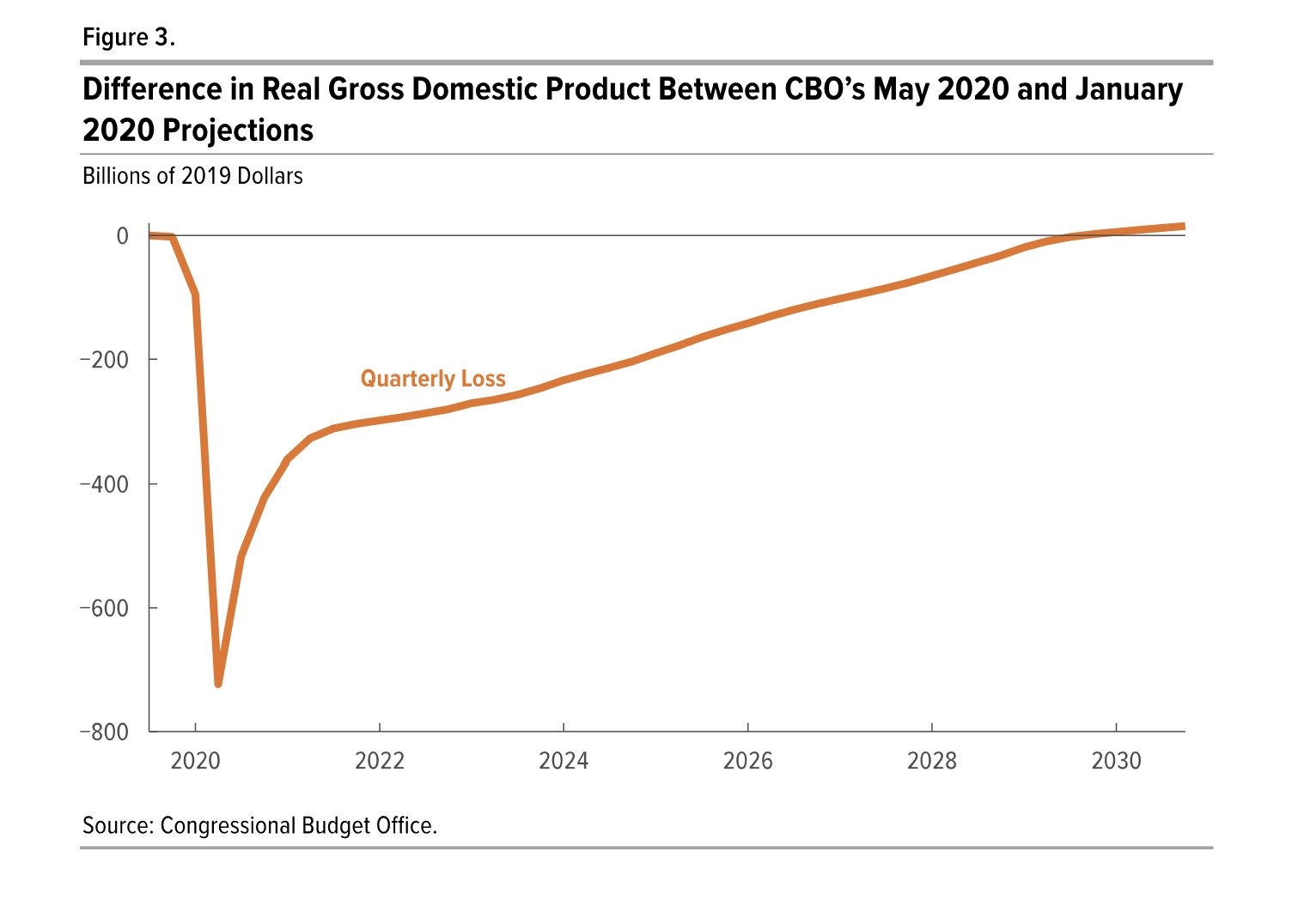

Romer cited an estimate from the Congressional Budget Office, which compares the projected GDP through 2030 before and after the pandemic, and forecasted that sum of all the projected quarterly losses of economic output through 2030 will amount to USD 7.9 trillion.

“We could spend USD 7 billion on testing and solve this pandemic. Instead, the pandemic is costing us USD 8 trillion. It’s just crazy that we are not spending the money to test and stop the losses.“

“We could spend USD 7 billion on testing and solve this pandemic. Instead, the pandemic is costing us USD 8 trillion. It’s just crazy that we are not spending the money to test and stop the losses.“

The US economy, however, started reopening this month without implementing sufficiently large-scale testing. Romer, disappointed, asked, “why we are not doing something that has such a high benefit-cost ratio?”

Intellectual Failure

“This is partly a political failure — we don’t have good leadership right now; It’s partly a social failure — we don’t have a consensus that people have to follow rules sometimes, even it’s inconvenient for them but good for the nation.”

It is, nonetheless, the intellectuals, especially the public health community, that frustrated Romer the most. He said the current situation amounts to an “intellectual failure.”

“The public health community don’t understand what has happened and why their usual methods are failing. Instead of stepping back, using logic and evidence to come up with a new plan, they just keep scolding everybody.”

“It’s like when a foreigner is talking to someone who doesn’t understand their language, they keep speaking louder,” Romer lamented, “That’s just not working. They need to look at the evidence and think hard to come up with a new approach.”

“In the US, there were many people who thought that we are the best-prepared nation in the world in dealing with pandemic. It’s okay to be wrong. Things change, and you can be wrong. What’s inexcusable is that you don’t recognize that you are wrong.”

Romer’s large scale testing plan also fell victim to the intellectual community’s inability to adapt, as the public health community in the US is opposed to such idea. “They have been able to undermine the progress that legislators are willing to make toward large scale testing.”

Not as bad as the Great Depression

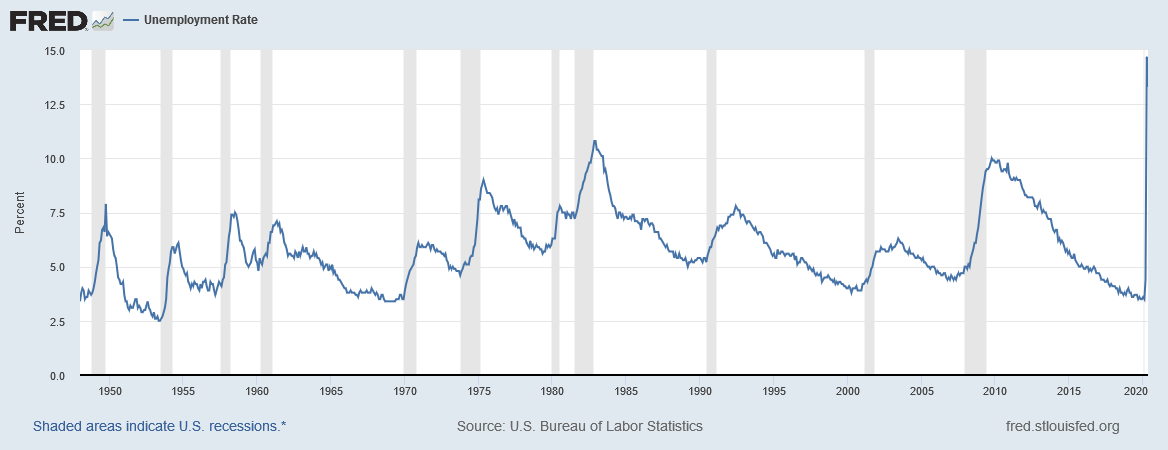

Despite his gloominess on the Covid-19 crisis, Romer sees a ray of optimism on the economic front. “The economic crisis has not turned out as bad as I thought,” the Nobel laureate said, “I thought this crisis would be worse than a Great Depression and we were going to reach 30% unemployment rate.”

The headline unemployment rate in the month of April and May was 14.7% and 13.3%. However, the Bureau of Labor Statistics added special notes in both jobs reports saying that there are misclassification errors, in which they have mistakenly counted “temporarily unemployed” during the shutdown as employed but “absent from work for other reasons”. Adjusting for these statistical errors, the April unemployment rate could be as high as 19.7%, and about 16.3% in May.

“A 20% unemployment rate is still the worst in my lifetime,” Romer continued, “it is the worst unemployment level since the Great Depression, but not as bad as during the Great Depression.”

Also, in this crisis the Federal Reserve has successfully propped up the financial system, helping to avoid a repeat of the Great Depression.

The US central bank cut the interest rate to zero and reintroduced quantitative easing in March, and since then launched 11 emergency facilities to support the financial system. “We haven’t seen a prolonged collapse stock market, bank failures or bank runs. So, we got this very high level of unemployment but without a financial crisis. It means that the economic crisis is not as bad as I feared it would be.”

Economics can certainly do more

The Fed’s effort to withstand a financial crisis, however, is often criticized as “only helping the rich”; and the social rest ongoing in the US shows further that people cared not only their economic well-being, but also the social equality and justice. How should economics, as a social science, help address these problems?

“Macroeconomists, or economists more generally, try to help people. They understand that this is about helping people. But their notion of what would be helpful for a person is very narrow, focusing on things like income, material consumption. They don’t think about a broader set of issues.” Romer commented in reply, adding that he thinks economists should pay more attention to topics like inequality, values, and morals.

“Economists have paid far too little attention to the questions about values, like trust or commitment to integrity; like how much value we should put on the acceptance of diversity, or the feeling of true inclusion — where a large group of people think of themselves as an ‘us’ and try to help other people in this group of ‘us’.”

“Many successful nations managed to sustain a notion that the citizens are ‘all in this together’. They share a common faith and they support each other.”

Yet, currently, the mainstream economics academia mostly focuses on “material gains and emphasizes on the value of selfishness; the notion that people being selfish will, by the invisible hand, lead to good outcomes in terms of material gain,” Romer said, “I think that model of what leads to a good society is too narrow. This is where the critical voices of economics play a helpful role.”

Romer’s influential work on “endogenous growth model” helped explain the importance of ideas and innovations in generating self-reinforcing improvement in human capital and long-term economic welfare, and the Nobel winning economist added that it is possible to directly integrate these values in formal economics models; but the problem is what kind of abstractions is most suitable for such task. For example, those values can be modeled as ‘norms’, he suggested, “I think economists should investigate that.”

“But you have to keep in mind that ultimately what matters are the facts, not the models. One of the failures in economics, especially macroeconomics, has been that economists put models above the facts; and they ignore the facts. Let’s not repeat that mistake!”

“Learn from the mistakes!”

On what lesson economics can learn from this crisis, Romer drew on several mistakes the public health community committed. For instance, the importance of accepting failures, “Once they get out of denial, failure can prompt people to take a look around, to see what they didn’t understand and failed to see. That’s the first step.”

Also, he thinks that credible intellectuals should focus on practical policy advice. “One of the things you have to do when you are offering advice is you have to take something as given; that there is something you can’t change. For example, we have a very high level of suspicion for tech firms in the US. This means that trying to use some kinds of digital contact tracing system is not going to work.”

“A practical policy advice must take account of the constraints,” Romer continued, “It’s a sign of denial and failure when a scientist says, ‘Policy X works in another county, and I think the US is just bad as it doesn’t adopt Policy X.’ That’s just shifting blame and the scientist isn’t doing the job.”

An edited transcript of the interview can be found here.

If you would like to reprint this interview on other platforms, please feel free to contact us at [email protected]

Cover photo – Photographer: Alexander Mahmoud / Copyright: Nobel Foundation

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡

I tune out when I see “new cases” or “cases” being taken seriously. It all depends on how many tests are given. So why bother to look at it? Especially when Deaths are available, a much more precise measure of what’s going on.

1st day of infection: false neg test rate: 100%. At day 4: 67%. By day 8 (the optimal time for testing) it decreases to 20%, the lowest false negative rate. Does your model consider the high testing false neg’s?

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/tests-may-miss-more-than-1-in-5-covid-19-cases