Welcome! This is the first installment of our interview series “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?”

“Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?” is an interview series with the aim to ask top economists a very important question: “Why haven’t economists come up with a new General Theory that can explain the Great Recession?”

The question is not why we haven’t seen a resurgence of old-style Keynesian economics, but rather an inquiry into how the macroeconomics academia changed since the Great Recession, and more importantly, why the responses from macroeconomists nowadays are different from their counterpart in the 1930s.

In this first installment, we talked to Prof. Scott Sumner, the Ralph G. Hawtrey Chair of Monetary Policy at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, where he is the director of the Program on Monetary Policy. He is also a professor of economics at Bentley University and Research Fellow at the Independent Institute. He is also a renowned blogger at The MoneyIllusion.

In the interview, Prof. Sumner discussed with us the findings from his new book, The Midas Paradox and his views on what caused the Great Depression.

For more “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?“, please follow our series via RSS or our twitter handle @Keynes2016

Q: EconReporter S: Scott Sumner

Q: In your book The Midas Paradox, you used the Gold Market Approach to explain the Great Depression. For starters, I would like to ask what the Gold Market Approach is? Why is it so important to understand the Great Depression?

S: The medium of account is the thing that everything else is priced in terms of. So for instance, the dollar in the US is the medium of account, everything is priced in dollars. Under the gold standard, there were two media of account, one was the dollar and the other was gold. That meant any changes in, say, the price level was both a change in the value of the dollar and the change in the value of gold, essentially by definition.

Now, traditional studies of the gold standard focus more on dollars than gold. It was usually a monetary approach, look at what was going on with the money supply.

I decided to look at gold, which I argued is, in some ways, a more important market. It’s an international market and the Great Depression was global, affecting all countries on the gold standard. So I was looking at why the price level falls globally, which means that the purchasing power of gold increased globally, and gold could buy more after this deflation. I argue that the fundamental factor driving deflation and the change in money supply was changes going on in the gold market.

It’s pretty easy to see this if you sketch out the supply and demand for gold. The supply of new gold from mining was fairly stable, so you are really looking mostly for how changes in demand for gold affected the price level. In particular, in the early 1930s, there was a lot of hoarding of gold, accumulation of gold by both central banks and also individuals later on. This increased the value of gold and it put deflationary pressure on the price level.

So the basic argument is that gold is the most useful way of thinking about the underlying cause of the big deflation we saw in the 1930s, especially the rise in the demand for gold.

Info – Gold Market Approach

Under the gold market approach, the market price is equal to the ratio of the nominal gold stock and the real demand for money.

P= G/g

where P is the price level, G is the nominal monetary gold stock and g is the real demand for monetary gold.

Then we can segment real monetary gold demand into two components, the gold reserve ratio (r) and the real demand for currency (m). The identity will turn into:

P= G*(1/r)*(1/m)

Thus, an increase in the price level can be generated by one of the three factors: an increase in the monetary gold stock, a decrease in the gold reserve ratio, and/or a decrease in the real demand for currency. Or we can say that the rate of inflation is equal to the percentage increase in the monetary gold stock, minus the percentage increase in the gold reserve ratio, minus the percentage increase in the real demand for currency.

Q: You have also challenged Keynesian’s view, arguing that there was no Liquidity Trap in the 1930s?

S: I think what was really going on was that there was a gold standard trap instead. When the US, for instance, did some QE in 1932, one of the problems that occurred is that it led to worry about a possible devaluation of the dollar. So people took gold out of the United States in fear of devaluation.

As gold flowed out of the US, that tended to reduce the money supply and offset the QE that the Fed was doing. So I argued that the real problem was not so much the money supply went up and didn’t help the economy, but rather the QE didn’t have much impact on the money supply.

A liquidity trap is where the money supply goes up a lot, doesn’t help the economy expand more. The gold standard trap was where you try to increase the money supply, but you really can’t because of the gold standard constraint. That’s why I believe that as soon as they devalued in 1933, they were able to generate inflation, which shows there really wasn’t a liquidity trap preventing inflation via monetary policy. It was the gold standard trap.

Q: I understand that you have read a lot of newspapers printed in the 1930s during your research. Can you give us a general view of what people at the time thought the real cause of the depression was?

S: First of all, we have to recognize that people looked at things very differently back then. They didn’t think about policies like inflation targeting as being very likely, especially a positive inflation target, which would have been considered inconceivable. At the time, the gold standard was very much locked in, it was essential to stay on the gold standard. That was viewed by most people as normal or the background, something that could not be challenged. Given that you have a gold standard, there are constraints on monetary policy. So people were not blaming monetary policy, they were blaming things that were indirectly affecting the demand for gold.

For instance, you had financial crises, first banking crises and then a crisis triggered by fear of devaluation of the dollar. These crises tended to make people more cautious, so they would hoard cash and gold. And this hoarding had a deflationary effect.

So one mistake people made is they didn’t realize the central role of the gold standard, they were focusing on things like how banking crises were affecting the gold standard.

The other mistake was that people assumed money was easy because the interest rate was low. And I think we made that same mistake again in 2008 and 2009. Interest rates being low does not mean money was easy, it could merely reflect the weak economy. And I think that was what it was reflecting at the time.

Q: In what way did Keynes affect the policymaking in the early 1930s, even before the publication of the General Theory in 1936?

S: He was what we would now view as a liberal. He favors a more active approach where the government tries to stop the depression. Early in his career, he focused more on monetary policy.

Once interest rates fell close to zero, Keynes become pessimistic about monetary policy, he didn’t think it worked very well. So he developed this liquidity trap view that once the rate falls to zero, you can’t do much more with monetary policy, instead, you use other tools like fiscal stimulus. He saw fiscal stimulus as the tool that could work even when the interest rate was zero.

In my view, as I’ve said in the book, what’s distinctive about Keynes’ General Theory, and I emphasize “distinctive”, is his view of what goes on at zero interest rates. Keynes also talks about the case where the interest rate was positive, it is not just about the zero interest rate case, but his most distinctive conclusion, the thing that is most controversial or interesting about Keynes’ view, mostly reflects what happens when interest rates are zero and especially what the government should do. To me, that is the core message of the General Theory. So Keynes sees a transition from monetary to fiscal policy as the interest rate falls to zero.

Q: In your view, do you think governments like the US and the UK follow his view on economic policy? Or it was the other way around, those policies helped him develop the General Theory?

S: Maybe to some extent. By the way, he was in favor of devaluing. Both Britain and the US devalued their currencies. So on that particular monetary issue, I think he is correct.

On fiscal, I think he had some influence, but not that much in the United States, at least not right the way. In the US, his greatest influence actually came after World War II. You have a whole generation of economists who were raised on his ideas and were moving into the position of power, as they got older. It is hard to change opinion right away.

In the Great Depression itself, Roosevelt did some fiscal stimulus, but maybe not as much as Keynes would have preferred. Then, late in the depression, you have the military build up in the US and Europe, and that seems to have help economies get out of the depression. This event supports the Keynesian view that fiscal stimulus can help expand the economy. It seems like the big spending on military weapons was having an effect. In my view, I think that the best argument for the fiscal stimulus is the World War II case. I am not really a fan of fiscal stimulus, but I think this is the one case you can point to.

Q: You have been critical about the effect of the NIRA (National Industrial Recovery Act). But what did economists at that time think about this particular policy?

S: Surprisingly, Keynes was critical of the NIRA, he did not think it was effective. He thought that they should have focused on promoting recovery before trying to raise wages. But there were mixed views on it. Many economists were critical, some supported it.

I think when you look closely at the data, it becomes clearer that what really went wrong was the wage policy. In my book, I cite 5 cases when Roosevelt tried to push up wages, and I argue that if you look closely at the monthly data, each time it seems to stop the recovery for a period of time.

I think the reason why some people missed it initially, was that the NIRA program was instituted during 1933, and that’s the year recovery from the depression started. So at the first glance, it kind of looks like it wasn’t a problem. But when you look at the monthly data, you see a very rapid growth in monthly production up until July, and that’s when the wage increase took place, and it stopped growth in industrial production for about two years. But because there was such a rapid growth in the four months before the NIRA, the level of output was still higher than it was before Roosevelt took office. So it’s a hard argument for me to make because the economy did begin recovery under Roosevelt, but I think it could have recovered faster without the NIRA. I believe the devaluation of the dollar was the really powerful factor pushing production higher.

Info – What is NIRA?

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was a law passed by the United States Congress in 1933 to authorize the President to regulate industries in an attempt to raise prices after severe deflation and stimulate economic recovery. The primary purpose of the NIRA was to establish industrial codes that would serve to prevent “ruinous” competition by setting minimum levels of wages and prices. These above market-clearing wages and prices were to be maintained by government-sanctioned industry cartels.

After the Blue Eagle Program was enacted in July 1933, the average nominal wage rate rose by an astounding 22.3% in just two months.

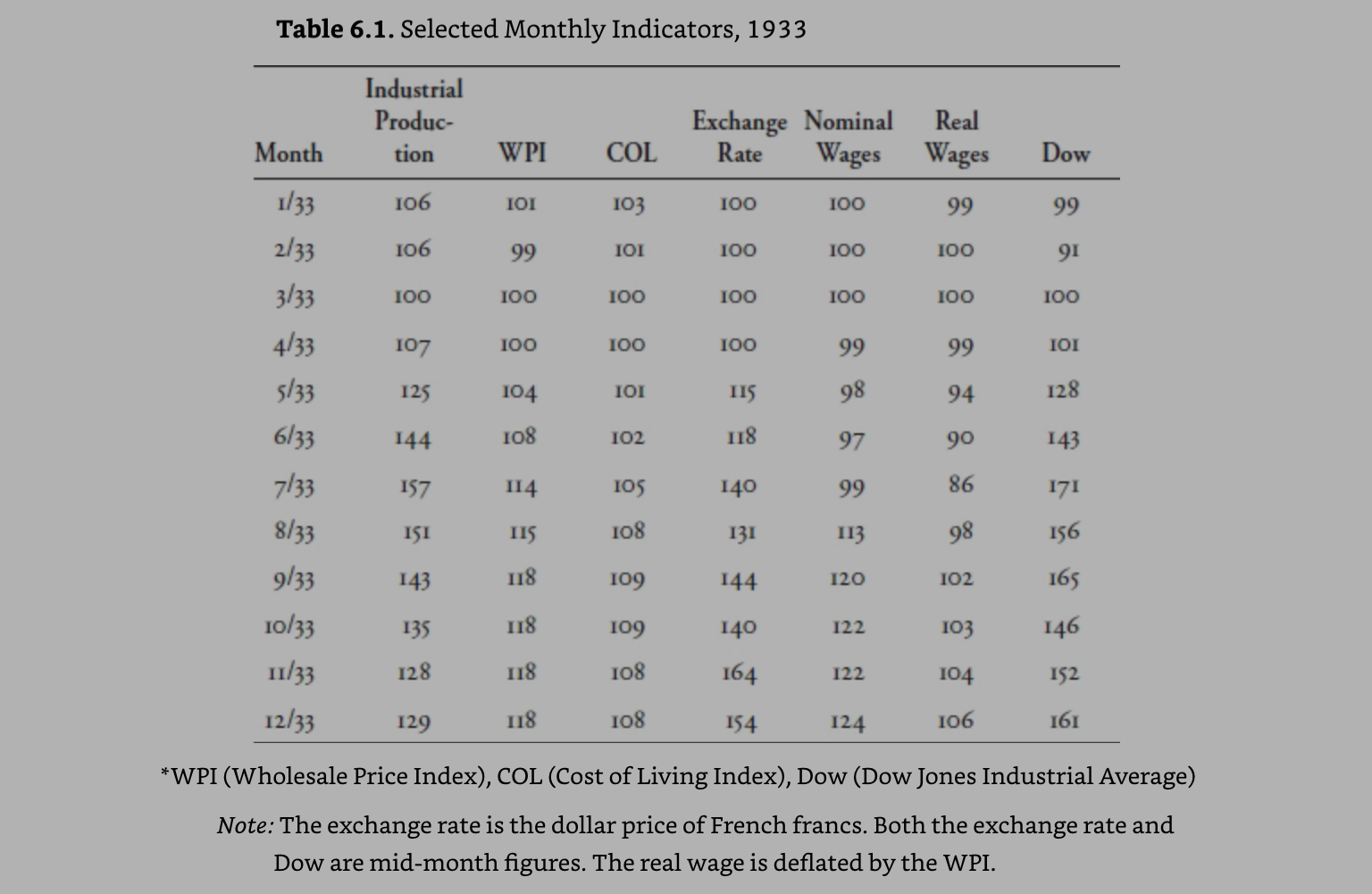

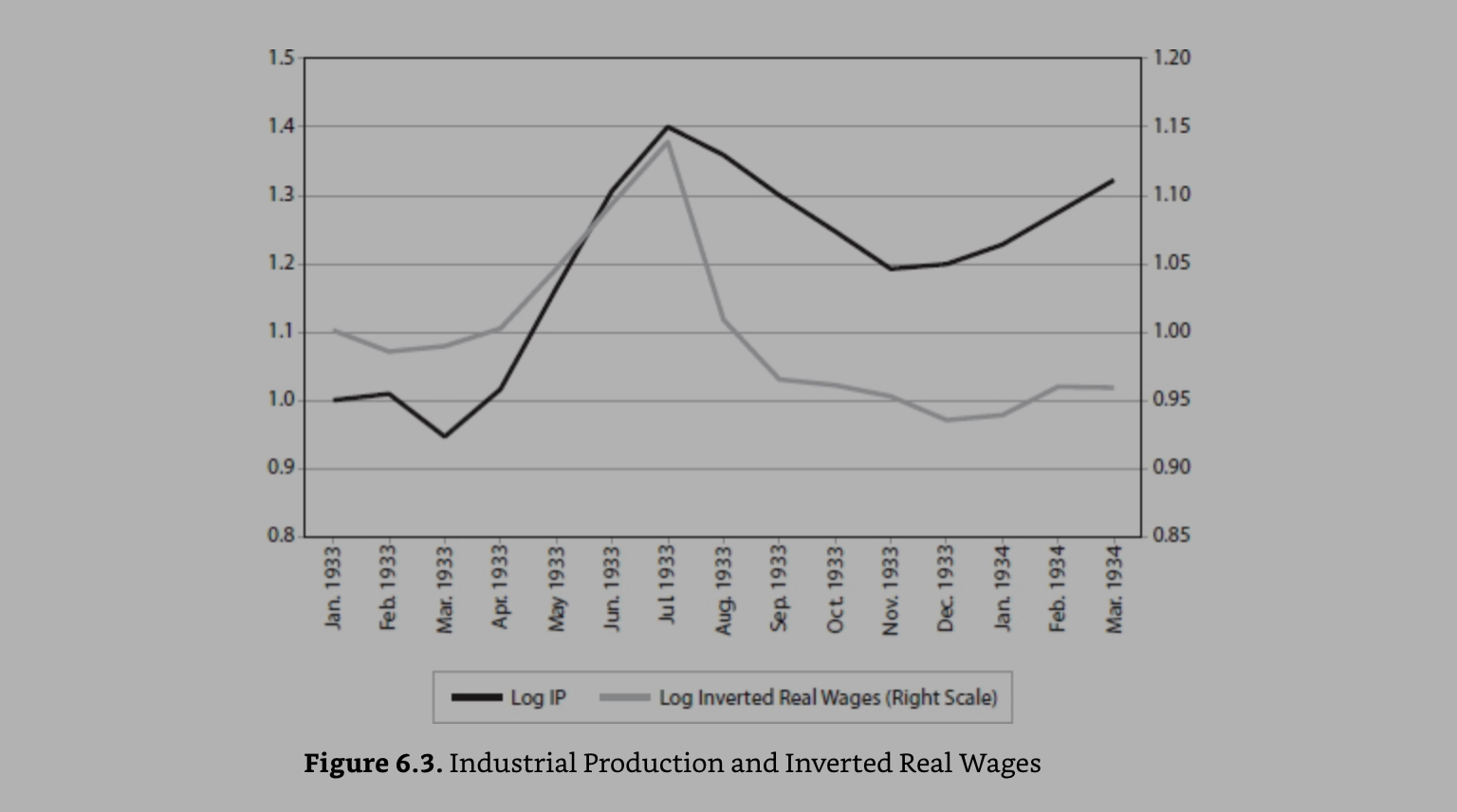

As we can see from the table extracted from the Chapter 6 of The Midas Paradox, the rise in nominal wage coincides with a sharp decline in industrial production. According to Sumner, this is the first time during the Great Depression when the path of prices and output began to sharply diverge. The Figure below shows the relationship between real wages and industrial productions during 1933.

Q: But it seems people still think the NIRA is a useful policy in periods like 1938, right?

S: Yeah, what happened is the NIRA kind of got replaced. Two years after it was instituted in 1933, the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional, in May 1935. But then FDR comes on with a new bill called the Wagner Act, which makes it easier to form labor unions. And that tended to push up wages a lot, especially around late 1936 and 1937. In 1937, wages go up very rapidly. And then later still, there were two minimum wage shocks, there was the first minimum wage in American history in 1938, and then it increases in 1939. So you have a bunch of different events that you can point to.

When the NIRA was ruled unconstitutional, Roosevelt came in with other policies like the legislation making it easier to form unions, or the minimum wage law, sort of doing the same things, and by that time the Supreme Court had become less conservative. And as the Supreme Court changed, it began to allow these bills instead of ruling them unconstitutional.

Q: But how come people back then still believed NIRA was a useful policy? What was the general thinking of people at that time?

S: You know, looking backward, I agree with you. But all I can tell you is that at the time things may have seemed that way.

Right now, in America, there is a big push to double the minimum wage, from 7.25 to 15 dollars an hour. To me, it is pretty obvious that it this likely to cost jobs, as workers become much more expensive, and very low skilled workers won’t be hired. But obviously a lot of people disagree with me, they just don’t see it that way. They think if we pay workers more, the workers will spend more, and that it will create jobs.

So everybody looks at the economy differently. You and I might think it is obvious that this has a negative effect on output, but it is a very complicated economy, and people can be looking at many, many different factors.

It is true that the economy did recover under Roosevelt, because of his other policies such as monetary devaluation. So while the economy was recovering, people could sort of say, “what are you talking about? It doesn’t seem to me that big a problem.” You really have to look at the data, the monthly data, and look at the timing of these changes in order to sort out the effects of each policy change.

Q: In the book, you have argued that the Keynes have misread the economic situation of the 1930s, and his theory is actually a special theory rather than a general theory. How come Keynes’ theory can have such a huge influence on academic macroeconomics?

S: Well, I also argued that the Keynesian economics changed over time when people began to realize some of the problems. So in that chapter you mentioned, I talked about how the Keynesian model evolved.

In the 1970s and 80s, there was the monetarist criticism of Keynesian economics. The monetarists saw some flaws in the model, it didn’t do well explaining inflation. So what happened in the 80s and 90s was that the Keynesian model changed and began being called New Keynesian. To me, that was actually the best period for macroeconomics, the 90s. The Keynesians had a more realistic view of the situation; they went back to monetary policy as being the preferred tool to stabilize the economy. So in the 90s, the new Keynesian models focus on monetary policy, inflation targeting. They also changed their views on some other issues, such as the natural rate hypothesis. They accepted that there is a natural rate of unemployment, an idea that came from monetarists like Milton Friedman.

So what happened is the monetarist ideas went into Keynesianism, improved it. I think it is wrong to just think that Keynes came up with the theory in the 1930s, it was accepted, and has always been the dominant theory.

But there definitely have been some aspects of Keynesian economics that have survived. And what we saw in the Great Recession is kind of a resurgence of the old Keynesian ideas; fiscal policy, the liquidity trap. Those ideas had kind of gone away in the 90s, and they came back in the Great Recession of 2008. And I think for the same reason as in the 1930s, the average person thought that monetary policy was “out of ammunition”. I don’t think that is true, but it looked that way, so fiscal policy became popular again.

Q: Some part of your argument is that Keynes sort of “Re-invented the wheels”. Do you think from the 1930s onward, economists had focused too much on fiscal policy…

S: I see what you are asking… Basically, I would have been happier if other economists from the 1920s and 30s like Irving Fisher, Ralph Hawtrey, and Gustav Cassel were listened to. I think they actually had a better view of what was going on in the Great Depression.

I guess I am not a big fan of Keynesian economics. But I will say one good thing about Keynes. I think Keynes was important because he emphasized that big drops in aggregate demand are a really bad thing, and the government needs to be more active in preventing that from occurring. A lot of people at the time were very passive, like “well, the government can’t do anything about this problem, just let it naturally heal.” But the Great Depression really was a disaster and caused a lot of other political problems. I think Keynes did play an important role by putting into the mind of governments the idea that they really needed to be active in preventing a big drop in aggregate demand. That’s the good part. The bad part was too much emphasis on fiscal policy, not enough on what sort of monetary policy can work even at zero interest rates.

(The conversation continues in Part II.)