In early May, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) intervened in the foreign exchange market by selling HKD 129 billion to the Hong Kong banking system over two days. The move was intended to defend its Linked Exchange Rate System as capital flowed into the city’s financial sector amid the so-called “Asian Financial Crisis in reverse.”

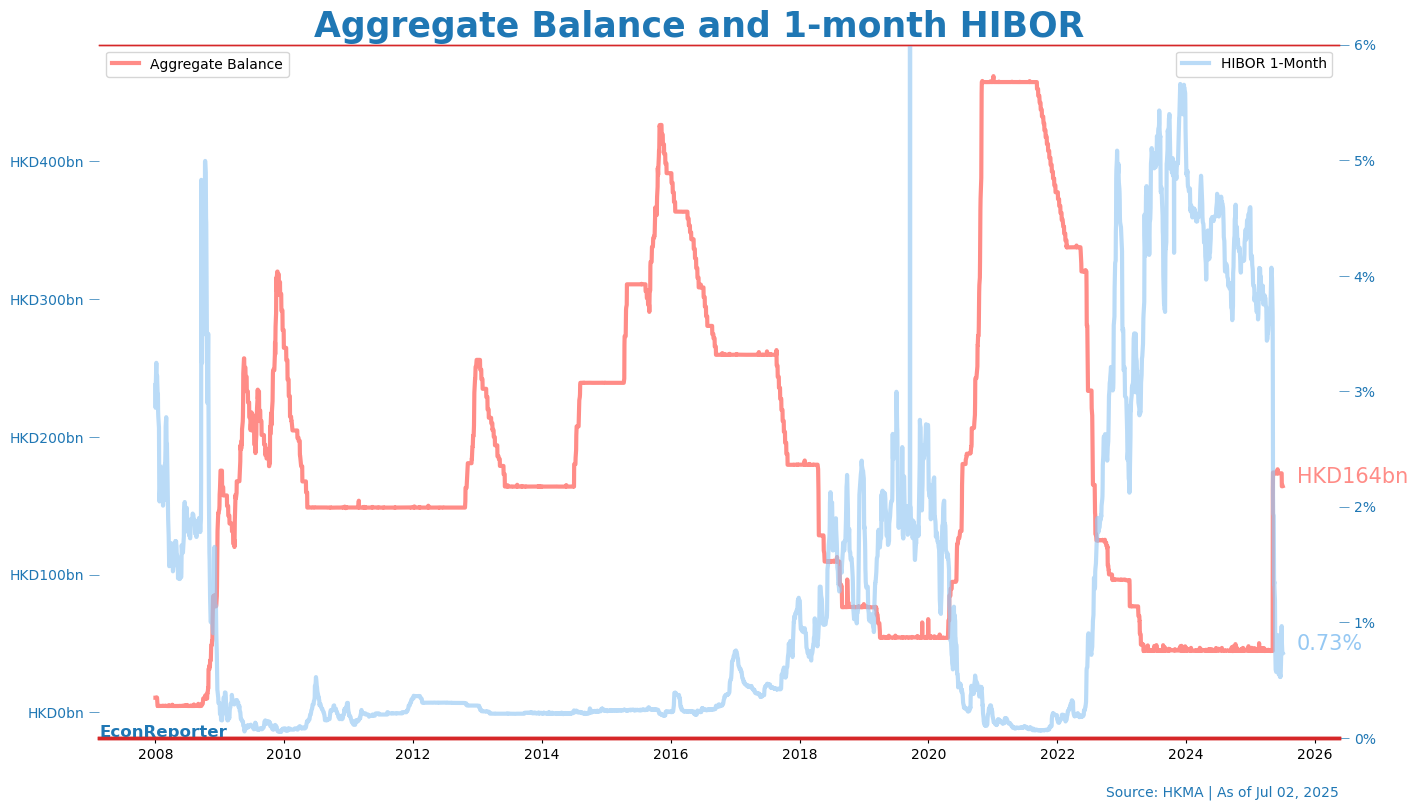

The one-month Hong Kong Interbank Offered Rate (HIBOR) has since dropped to just 0.75% as a result of the surge in interbank liquidity, compared to around 4% before the massive capital inflow.

The 30-day SOFR, the US’s interest rate counterpart, is currently around 4.3%. This substantial interest rate gap between US and Hong Kong generated a lot of media interest as the traditional narrative about Hong Kong’s Linked Exchange Rate System is that when comparable interest rates in Hong Kong and the US diverge, market participants would engage in arbitrage and compete away the interest rate spread via arbitrage. However, this has not happened.”

Indeed, a more careful study of Hong Kong’s currency peg reveals that this surprisingly low-interest rate environment can be interpreted as a result of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s policy choice.

How Linked Exchange Rate System works?

Under the Linked Exchange Rate System, the HKMA must acquire USD from the market whenever the HKD exchange rate becomes “too strong”—that is, when it strengthens beyond the HKMA’s trading limit of HKD 7.75 per USD.

- The purpose is to supply more HKD to ease excess demand for HKD; or, equivalently, to take away USD from the local banking system to reduce excess USD supply.

- The weak-side trading limit is HKD 7.85 per USD. Breaching it would prompt the HKMA to sell USD to local banks and absorb HKD from the banking system.

What is Aggregate Balance?

The Aggregate Balance is the sum of all clearing accounts which banks in Hong Kong hold with the HKMA.

- It can be interpreted as an indicator of the level of interbank liquidity within the Hong Kong banking system.

- When HKMA intervenes in the foreign exchange market, the de facto central bank either buys HKD from or sells HKD to the banks. These interventions reduce or increase the amount of HKD held in the Aggregate Balance.

The amount of liquidity banks hold in the Aggregate Balance in turn determines the level of interbank interest rate in Hong Kong’s financial system: the Hong Kong Interbank Offered Rate (HIBOR). For example, Aggregate Balance and one-month HIBOR exhibit quite a stable inverse relationship.

It is safe to assume that a reduction in Aggregate Balance is needed for HIBOR to rise back to a comparable level as the US interest rates.

The Overlooked Tool: Exchange Fund Bills and Notes

Most commentators focused on the traditional narrative that the interest rate gap would kick start carry trade. As investors borrow HKD to invest in USD assets, this capital flow would first weaken HKD exchange rate against the USD and by a certain point it would trigger HKMA’s convertibility undertaking and “force” the de facto central bank to buy HKD from the banks and sell USD.

This is what has not happened, leaving many commentators puzzled.

However, many commentators have missed an alternative method the HKMA can use to drain liquidity from the Aggregate Balance: issuing additional Exchange Fund Bills and Notes (EFBNs).

EFBNs are HKMA-issued HKD debt securities backed by USD exchange reserves; thus, they are counted as part of the HKD monetary base. These debts are mostly held by banks in Hong Kong, which can use them as collateral to conduct intra-day repo transactions with the HKMA and to borrow overnight liquidity from the de facto central bank’s discount window.

Since the Fed engaged in quantitative easing (QE), the HKMA has issued a large volume of EFBNs. The total amount of EFBNs outstanding was less than HKD 200 billion at the start of 2008; today, there are over HKD 1.3 trillion of EFBNs in the Hong Kong financial system.

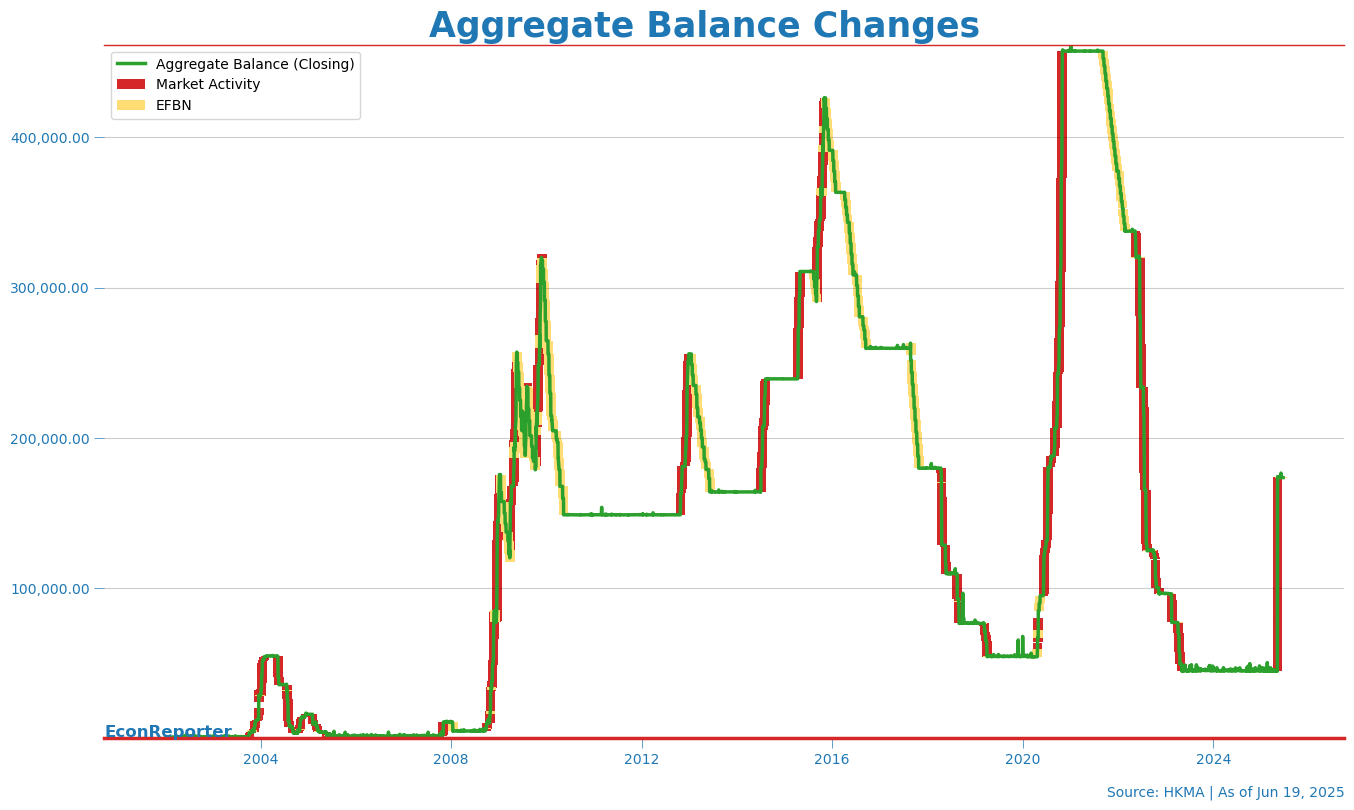

In the Hong Kong Linked Exchange Rate System, banks have a choice holding liquidity in form of deposit with HKMA in the Aggregate Balance or in form of EFBNs. Whenever a new batch of EFBNs is issued to the banks, the HKMA withdraws an equivalent amount of HKD from the banks’ clearing account, reducing the Aggregate Balance by the same amount.

So, in effect, the HKMA can absorb “excessive” liquidity from Aggregate Balance with additional issuance of EFBNs. As shown in the graph below, it’s clear that additional and reduction in issuance of EFBNs (highlighted yellow in the graph) has been as important as a driver for changes in Aggregate Balance as HKMA interventions (highlighted red).

So, this is a simple yet true argument: the HKMA can immediately eliminate the HK-US interest gap by issuing additional EFBNs.

Why HKMA hasn’t done that (yet)?

The HKMA has so far refrained from using such tactics. Why?

First of all, the HKMA’s official stance has always been that it “doesn’t have an interest rate policy” and it will not adjust EFBN issuance to “target Hong Kong dollar interest rates at certain levels.” But this should normally mean it doesn’t have a policy to deviate Hong Kong’s interest rates from the ones priced in the USD, instead of letting the interest persist.

Second, a simple reading of the graph suggests that the current Aggregate Balance is close to the level where the HKMA has historically stopped issuing additional EFBNs and allowed market activities to take over.” So, they may be waiting for the exchange rate to hit its weakside convertibility undertaking (at HKD 7.85 per USD) and intervene in the foreign exchange market instead.

Indeed, HKMA has so far intervened twice in the foreign exchange market, bought HKD 29.4 billion from banks in total, reducing the Aggregate Balance to about HKD 144 billion.

Third, a lower interest rate environment provides the temporary economic stimulus Hong Kong’s weakening local economy urgently needed, especially through lower mortgage payments, which are usually based on a variable rate tied to the one-month HIBOR. Is the public likely to accuse the HKMA of failing to immediately correct this interest rate ‘glitch’? It seems unlikely.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project striving to provide top-notch coverage on everything related to economics and the global economy.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡