Last Updated:

In the last two weeks, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority sold about HKD 20.7 billion to the banking system, according to HKEJ’s report.

The de facto central bank of Hong Kong had to acquire USD from the market because the HKD exchange rate is too strong, rising to the trading limit of HKD 7.75 per USD under its Linked Exchange Rate System. It has to supply more to ease the excess demand for HKD. Or, equivalently, it has to take away some USD from the local banking system to reduce the excess supply of it.

What if I tell you, behind the boring news headline, there is actually a wonkish story about how the Hong Kong central bank took advantage of the monetary easing by the Fed in the last 12 years and created a new set of policy options that it can now use to actively manage the inflows created by the new round Fed easing under the Great Lockdown.

Why does capital flows into Hong Kong?

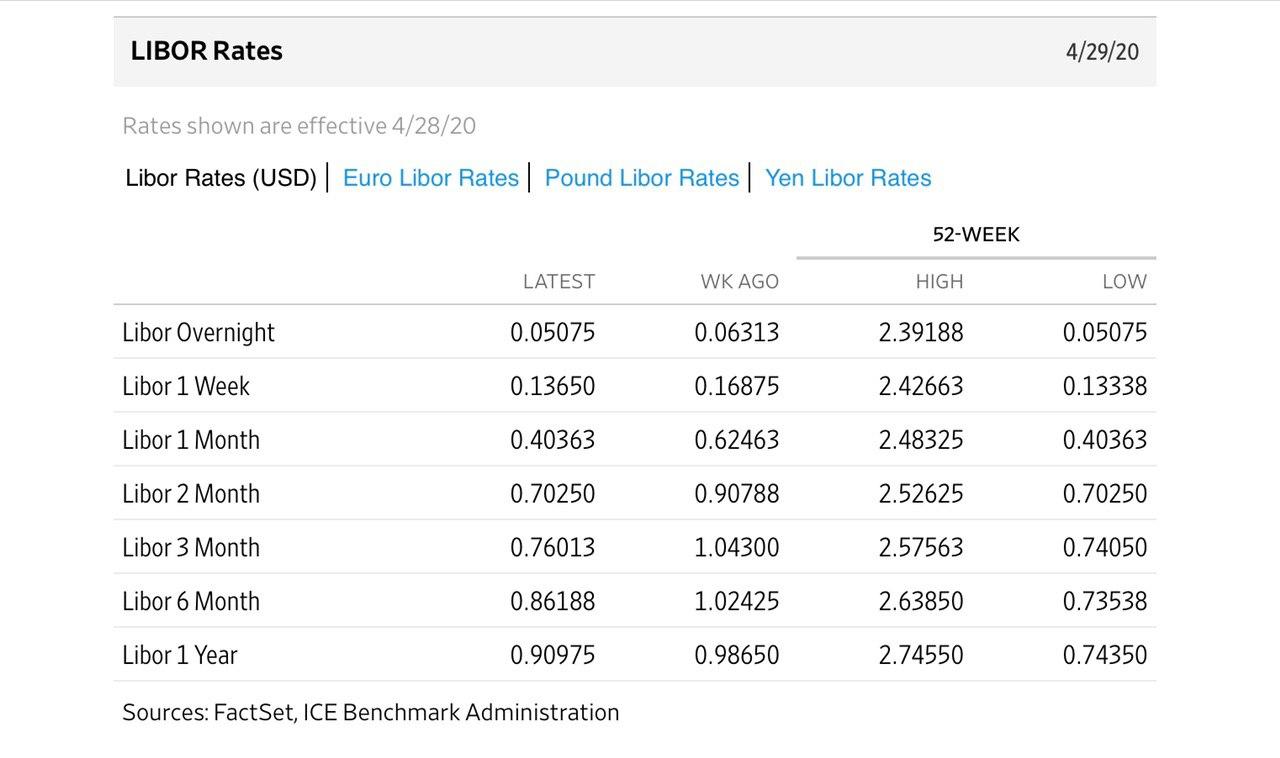

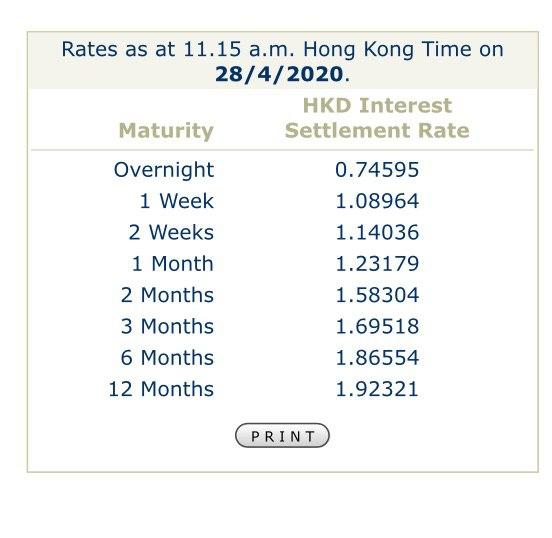

But, first, let’s learn some basics. Why is capital flowing into Hong Kong? One reason is that the interbank interest rate in Hong Kong (HIBOR) is now higher than its counterparts in USD (LIBOR), and this positive spread makes it attractive to invest in HKD assets and earn the extra yield.

As you can see from the screenshot of the two rates, as of April 28, HIBOR is significantly higher than LIBOR in all maturities.

The basic principle of the linked exchange rate system predicts that, in the presence of such substantial positive interest rate differentials, investors will pour money into HKD. By buying USD from and selling HKD into the banking system, HKMA will ease the demand for HKD and drive down the HIBOR; this goes on until the interest rate spread falls to a negligible level.

So, the capital inflow can be seen as a feature of how the linked exchange rate system drives the HKD interest rate toward the USD ones.

HKMA has another option now…

Here, nonetheless, I would like to discuss an alternative way that can equate the HKD and USD interest rates, which relies much less on the capital inflow or HKD exchange rate appreciation. But again, I have to explain a bit more about the Linked Exchange Rate System.

Banks in Hong Kong hold clearing accounts in the HKMA, which they use to keep a certain amount of HKD liquidity, for settling interbank payments and payments with HKMA. Aggregate Balance, the sum of balances in all these clearing accounts, can be interpreted as an indicator of the level of interbank liquidity inside the Hong Kong banking system. And, when there is capital inflow and the HKMA sells the HKD to the banks, the money mostly goes into the Aggregate Balance.

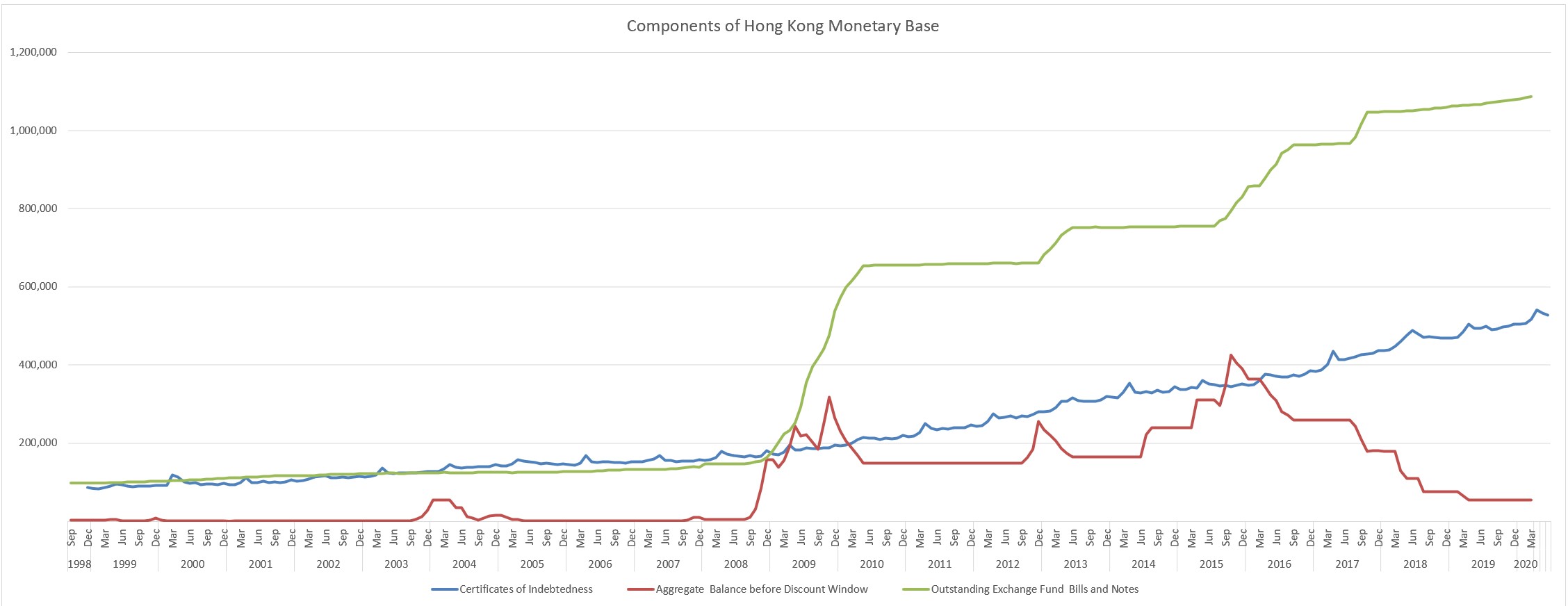

Aggregate Balance is not the only place banks can hold HKD liquidity, however. They can also keep the money in the form of cash (or certificates of indebtedness, in HKMA jargon), and Exchange Fund Bills and Notes (EFBN).

EFBN are short-term debts issued by the HKMA, backed by equal value foreign exchange reserves in the exchange fund. The Hong Kong de facto central bank issues the EFBN to provide the banks with a way to store their excess liquidity in the system and earn interest.

The monetary base of HKD , hence, comprises Aggregate Balance, Cash in Circulation and EFBN. These are the three ways banks can store their HKD liquidity.

In general, the interbank interest rate, HIBOR, is affected by the money supply and demand in Aggregate Balance. An elevated HIBOR, then, can be interpreted as a signal of insufficient supply of HKD in the aggregate balance.

A high-interest rate, relative to other currencies, is also an incentive to increase the HKD supply. More capital inflow will prompt the HKMA to exchange USD into HKD, and inject it into the Aggregate Balance.

But if you think about it, the HKMA has another way to lower the HIBOR — it can buy EFBN from banks and pay them with HKD, which will go into the Aggregate Balance.

As of April 29, the Aggregate Balance of the banking system is around HKD 84.7 billion in size. What about the EFBN? The total outstanding EFBN amounts to HKD 1.07 trillion, of which the banking system holds HKD 951 billion.

So, banks hold more than ten times of their HKD in EFBN than in Aggregate Balance. The HKMA can, in theory, add, say, HKD 400 billion into the Aggregate Balance, simply by buying the EFBN off the banks. Positive interest spread? Probably gone the next day.

The question, then, is why not?

If you agree with the above argument, then the question will become “why doesn’t the HKMA actively sell off EFBN and stop the HKD exchange rate from being pushed to its limit?”

Arguably, this is a new problem, or luxury, that HKMA had not had much previous experience with. The outsized amount of EFBN outstanding is a situation created by the Fed’s series of quantitative easing since 2008. In Nov 2008, the month the Fed started its first QE, the outstanding EFBN was only about HKD 154.6 billion.

In other words, an additional HKD 850 billion of EFBN was issued over the last 11 years or so. The HKMA had never before held so much ammunition that it can use to directly influence the HKD interest rate.

Also, think about the trade-off for an active EFBN intervention.

If HKMA lets the old mechanism run its course, i.e., allows the positive interest spread to attract foreign investors to gradually pour money into HKD, the “consequence” is then more HKD liquid assets for banks in Hong Kong, and increased foreign exchange reserves for the Hong Kong economy. These seem to be good things to have.

Maybe, you can argue, in the short run, the HKD interest rates are elevated, meaning some economic growth in Hong Kong is sacrificed during this pandemic-induced economic crisis. But in general, the world is stuck in the low-interest-rate environment now, the so-called elevated level we are talking about is just around one percentage point. The harm it can inflict may be limited.

So, there seems to be an obvious benefit of sticking to the old way, letting capital inflow to do the job of eliminating the interest rate spread, and keeping the HKD exchange rate at the strong end of the Linked Exchange Rate System.

Also, the HKMA said on April 9 that it reduced the size of four issuances of Exchange Fund Bills, which in effect injected HKD 20 billion into the Aggregate Balance, which was about HKD 54 billion on that day. So it is, in fact, doing the “sell EFBN” strategy to ease the liquidity strain in the interbank market.

The lesson

The overall lesson I hope to draw here is that the EFBN is an important feature of the Hong Kong linked exchange rate system, but unfortunately neglected by many commentators.

By amassing a huge amount of HKD liquidity in EFBN inside the banking system during the last few rounds of QE in the US, HKMA now holds a new policy option — active intervention of the interbank interest rate, capital inflow, and the exchange rate. One may even argue that the elevated HIBOR currently observed is a result of too much EFBN issued.

While the automatic rebalancing feature of the linked exchange rate system is highly praised by many, this potential active management side of the system shouldn’t be completely ignored. This is a currency board design that some other countries can learn — a system that not only can withstand the capital flow volatility brought by the QEs but can also benefit from it.

Some further discussions…

The above was the original argument I set out in my draft and planned to elaborate. During my research, nonetheless, I realized some related details that are worth discussing further, and may refute some of my speculative arguments. So I now lay them out here so we can come back to them in future discussions.

- HIBOR is not only significantly higher than LIBOR now, it is also higher than the yield on the EFBN. For example, HKMA sold HKD 33.4 billion worth of three-month Exchange Fund Bill that carries an average yield of 0.48%. The HIBOR of the same maturity on that day was almost 1.7%. This is much higher than the usual spread of around 0.5% in January.

The large gap between EFBN rate and HIBOR seems to suggest that the market is in demand for more EFBN. The HKMA-issued short term debt can be interpreted as a high-quality USD-linked quasi-safe asset, and in times of extreme market volatility, it becomes extra attractive. It does raise the question of whether a reduction in EFBN supply is the right way to go.

- Yield divergence also happened in 2007, and for a brief period of time some of the shortest-maturity Exchange Fund Bills recorded a negative yield.

The HKMA Chief at the time Joseph Yam wrote that the negative rates meant that “the banks are even prepared to pay for holding them, instead of just sitting on the money in their clearing accounts”, against the backdrop of the sub-prime mortgage crisis that was erupting in the US. The solution HKMA resorted to back then was to increase the supply of Exchange Fund Bills to drive back up the yield.

- One conjecture is that EFBN as a quasi-safe asset can also be a reason for capital inflow into HKD. HKMA can choose either to increase or reduce the supply of EFBN to deal with the situation.

More supply will push the yield of EFBN higher, closing gap between HIBOR and EFBN yield, and create more monetary base in Hong Kong. HKMA can keep doing that until the flight to safety period ends.

Or, HKMA can educes the supply of EFBN, drag down both EFBN yield and HIBOR, and fence off some of the demand for HKD with the lower yield.

- One relevant feature of the 2007 negative Exchange Fund Bill yield period was that the banks increased usage of intraday repos of Exchange Fund paper with the Hong Kong central bank.

Intraday repo allows the banks to use their holdings of Exchange Fund Paper as collateral to obtain intraday or overnight HKD liquidity for their interbank payment. “Sometimes over 80% of the Exchange Fund paper held by the banks was used for this purpose,” Yam wrote at the time.

In the current regime, HKMA also has the Standby Liquidity Facilities, through which banks can use EFBN and other high-quality liquid assets as collateral to obtain one-month liquidity to handle “any unexpected liquidity tightness”. Given the current positive interest rate differential, it is interesting to see whether the banks have utilized these repo facilities to turn their EFBN into HKD liquidity to meet their liquidity needs.

Or more importantly, why is the repo arrangement unable to deal with the HKD liquidity shortage happening in the Hong Kong banking system right now? The banks now own more than HKD 951 billion of EFBN, if the cost of the repo is low enough, they should be able to handle the HKD needs very easily and eliminate the HIBOR-LIBOR spread in a blink. But this is not happening. Why?

Unfortunately, HKMA said it “does not disclose information about usage of the facilities, unless exceptional circumstances pertain where there is a strong case for doing so to maintain monetary and financial stability.” So, it makes it hard to learn the answer at this stage.

EconReporter is an independent journalism project dedicated to providing top-notch coverage on all things economics.

💡 Follow us on Bluesky and Substack for our latest updates.💡

During the past 30 years, more than 90% time, hibor is lower than libor and the capital is pouring into Hong Kong. Apparently,the hibor-libor spread is not the main reason for capital inflow.