This is the latest installment of our interview series “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?”. “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?” is an interview series that explore the evolution of macroeconomics academia since the Great Recession. Do we have some revolutionary changes in the macroeconomics after 2008, just like we have had the “Keynesian Revolution” after the Great Recession? Why haven’t economists come up with a new General Theory after the Great Recession? We ask influential economists for their answers on these questions.

Atif Mian on The Major Shifts in Macroeconomics Since the Great Recession | #WITGT21 Interview Series |

The honorable guest for this installment is Atif Mian, Theodore A. Wells ’29 Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University, and Director of the Julis-Rabinowitz Center for Public Policy and Finance at the Woodrow Wilson School. Professor Mian has done a lot of excellent works on the connections between finance and the macroeconomy.

Professor Mian has discussed what he thinks are the “revolutionary” changes in the macroeconomic academia since the Great Recession in Part one of our interview. In this installment of the interview, Professor Mian explains the major findings in his recent research papers “Household Debt and Business Cycles World Wide” and “How Do Credit Supply Shocks Affect the Real Economy? Evidence from the United States in the 1980s”, and the important implications of these two papers.

Photo Credit: Financial Times Youtube Channel

Q: EconReporter M: Atif Mian

(The interview is edited for clarity. All mistakes are ours.)

Q: In a recent research paper “Household Debt and Business Cycles Worldwide”, you have found that an increase in household debts in the lag years has a negative correlation with the GDP growth in the subsequent years. Do we know whether this relationship between the household debt and the GDP growth is merely a correlation or a causation?

Household Debt and Business Cycles Worldwide

An increase in the household debt to GDP ratio in the medium run predicts lower subsequent GDP growth, higher unemployment, and negative growth forecasting errors in a panel of 30 countries from 1960 to 2012.

M: That’s a very important question. Let me first tell you the extent to which we can talk about causation versus correlation in this paper — “Household Debt and Business Cycles World Wide”. Then I will briefly highlight a new paper [How Do Credit Supply Shocks Affect the Real Economy? Evidence from the United States in the 1980s] that we, the same authors, i.e. Amir Sufi, Emil Verner and I, try to dig deeper into the causation versus correlation question.

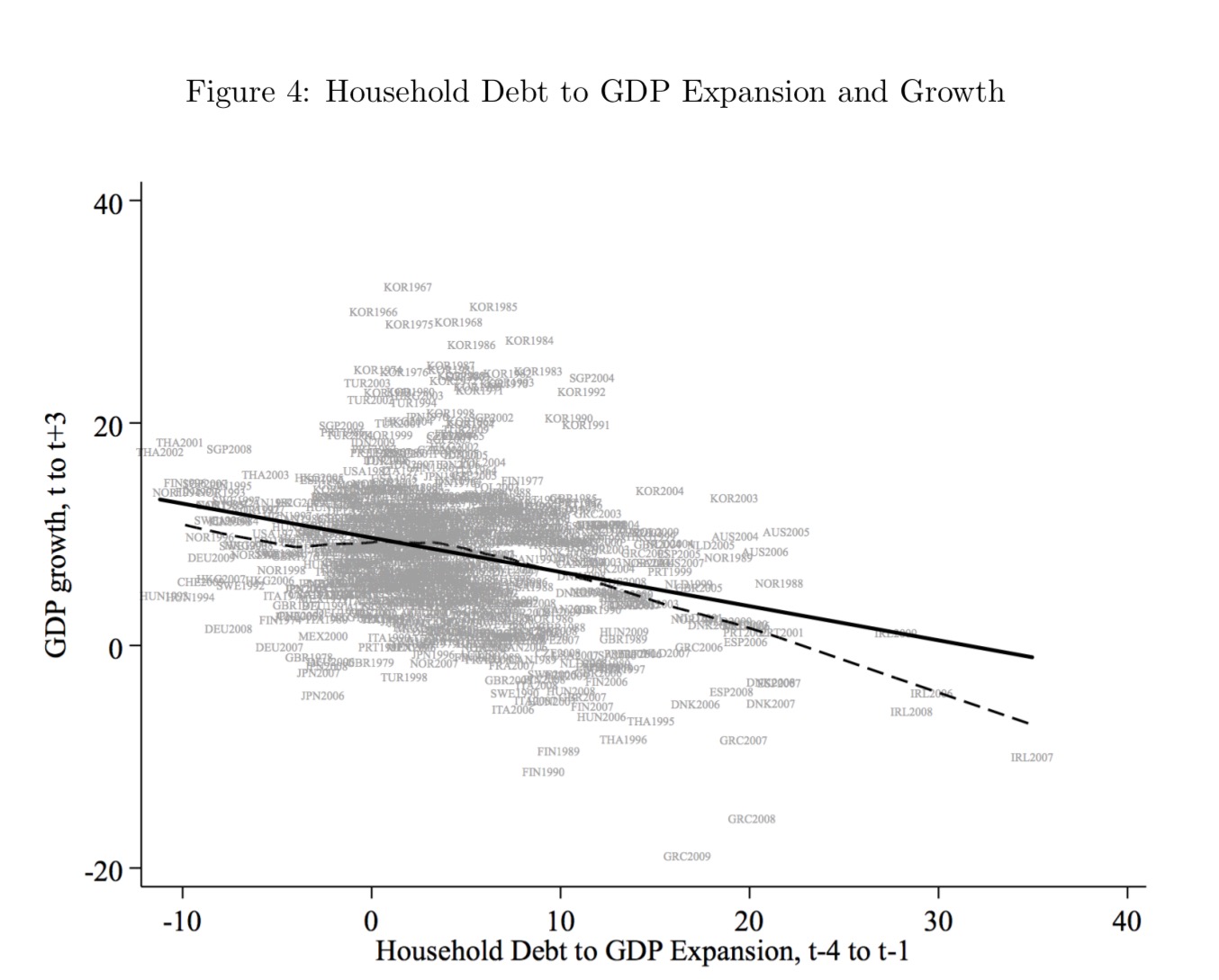

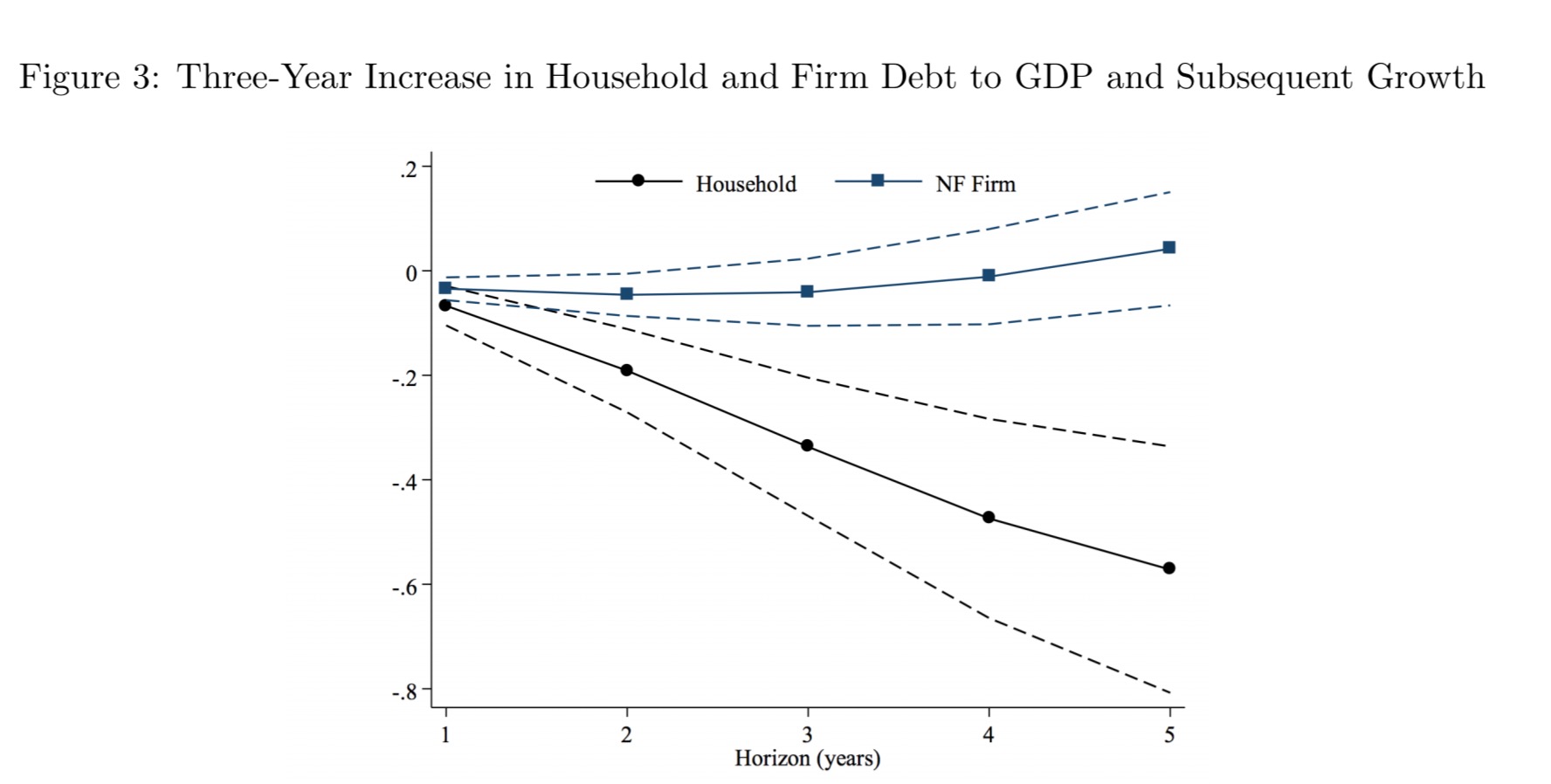

The paper that you’ve mentioned is a paper that uses cross-country panel data from the 1970s onwards. We are looking at the developed countries, like the OECD economies. What we’ve shown in that paper, among other results, is that growth in credits “predicts” a slowdown in the macroeconomy. Here I use the word “predict” in a statistical sense, and let’s not address the causation question for a moment.

However, not all kinds of credits predict a slowdown in the economy. Overall, credits have two components, the household credits versus the credits that are going to the corporate sectors. It is the credits that go into the household sector predicts the slowdown but not the credits to the firms. So, it’s more credits going to the household sector that predicts the slowdown in GDP. That’s one of the key findings in that paper. And while you can see this situation in the 2008 Recession in the US and in some other developed countries, the result is not just a phenomenon of the 2008 cycle.

Let’s come to your question. How should we think of this result? Is this just a correlation? Or can we go a step further and call it a causal result? We can start off by describing it as just a correlation in the data. Even a correlation is very useful in shifting to the model that is more likely to be a legitimate description of the economy.

For example, in the traditional Permanent Income Hypothesis world, people borrow in anticipation of higher income going forward. With such intuition in mind, even the correlation is very useful because we cannot explain this negative predictability in the Permanent Income Hypothesis world, which you should expect a positive correlation between growth in household credits today and the subsequence income growth. We actually found the opposite — a very strong negative correlation. So, even if it is just a correlation and without digging into the causation question, one can already reject a certain class of model that is influential in the academic literature on the international business cycles. That’s point number one.

Having said that, it’s still important to try to understand the causation versus correlation question. OK, we have shown that credit shocks have negative predictability for subsequence growth. But where is the credit shock itself coming from? If we could understand where the credit shocks are coming from, we could perhaps get a better understanding of this causation versus correlation issue.

So, what we need is a natural experiment where for some “exogenous” reasons we can shift the credit supply around and see its impact on the economy. That’s the idea of the experiment that one would like to do. We tried to set up that experiment in a couple of different ways in this paper, and there is a follow-up paper that does something different.

We have done a couple of things in this paper. The first one is that we have looked at the case studies of European countries joining the Eurozone. Why is this a useful case study? Because we know that by joining the Eurozone, the peripheral countries benefited disproportionately in the financial perspective. The credit spreads for peripheral countries like Greece collapsed a lot more than the credit spread for core countries, like German, for example, who we are considered to be very safe already. So, joining the Eurozone, in other words, was like a big and positive credit supply shock for countries like Greece. You can use these kinds of episodes to generate the shifts in credit supply by looking at the reduction of the credit spreads.

One can also use such intuition more broadly. In the same paper, we put together some data on the spreads and we use the decline in the market spread as an instrument for positive shocks to credit supply. In the VAR setting, we show that when you use a decline in market spreads as an instrument for credit supply shocks, and under certain excruciating restrictions, if the initial shock is a reduction in credit spread, and such credit supply shock boost the credits in the short-run, and it ultimately leads to the slowdown in GDP growth, one can argue that these patterns we are observing can be interpreted more in the causal sense. That is the extent to which how we can address the causation versus correlation question in that paper.

What we’ve done more recently is that we have written a new paper “How Do Credit Supply Shocks Affect the Real Economy? Evidence from the United States in the 1980s”, which will be coming out in the summer at the NBER conference. In that paper, the key question is: “Can we construct a natural experiment where we have a change in credit supply for a reason that is not directly related to anything else that is happening in the economy?”

How Do Credit Supply Shocks Affect the Real Economy? Evidence from the United States in the 1980s by Atif R. Mian, Amir Sufi, Emil Verner :: SSRN

We explore the 1982 to 1992 business cycle in the United States, exploiting variation across states in the degree of banking deregulation to generate differenti

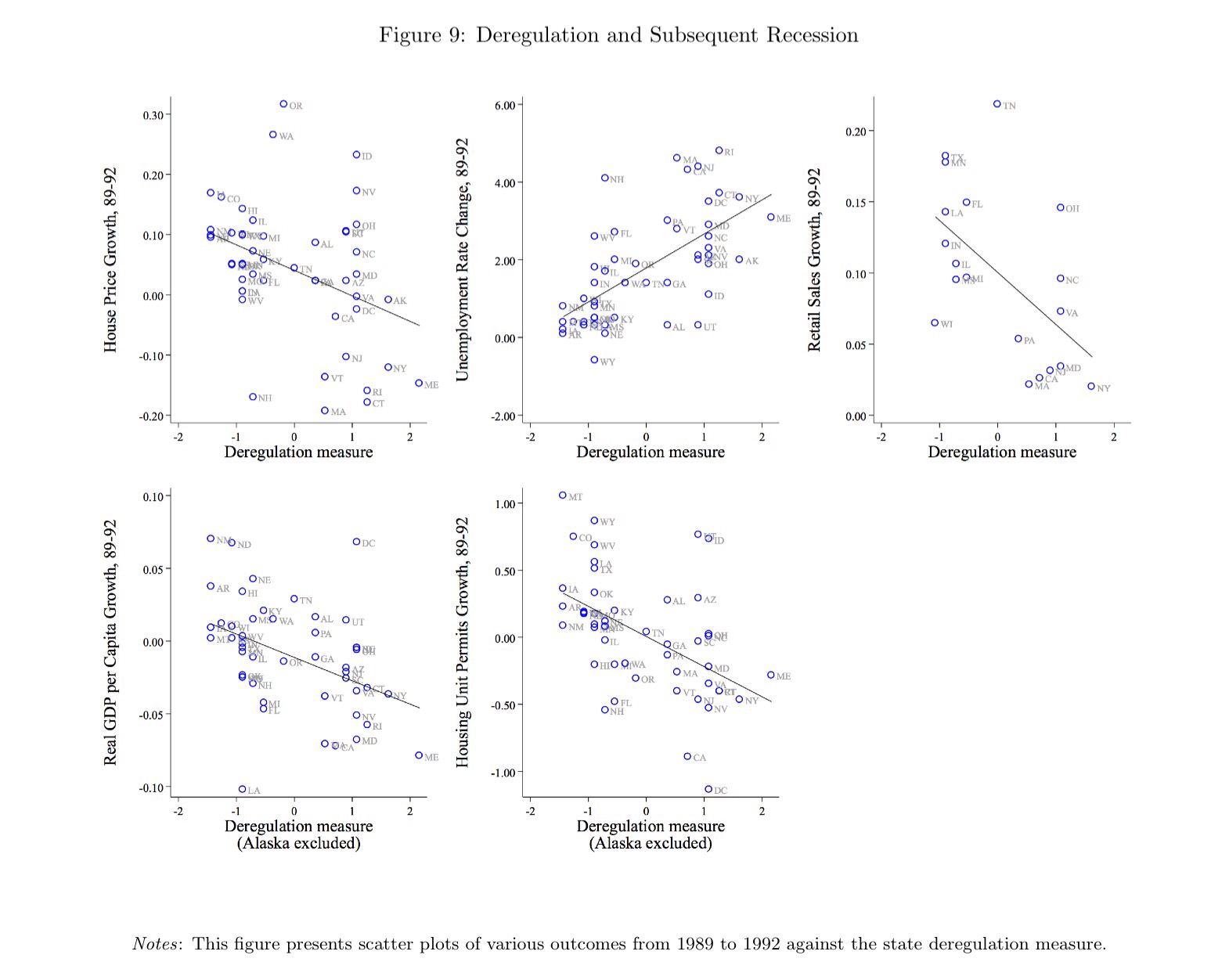

What we do in that paper is that we look at the banking deregulation wave in the 1980s in the US. There is a lot of literature on that and people have argued that, for reasons largely exogenous to the macroeconomy, some states deregulated earlier and more than others. We use the experiment to see how does the cross-sectional variations across states in the timing of the banking sector deregulation impact the business cycles.

What we find is exactly like the trend in the paper that is using the cross-countries data. We find exactly the same pattern across states in the US, which is that the states which deregulate early, there are positive booms in credit which amplify the business cycle such that they see a faster growth in GDP in the short-run. However, that is followed by the recession, and the recession is much deeper in precisely the same sets of states that are deregulated earlier and had the bigger credit booms.

By the way, the credit boom is concentrated in the household sector. The growth in household credit is driven by the early deregulation in certain states, and that drive the boom-and -bust cycles in those states.

The punchline of this line of works essentially is that not only credits, household credits, in particular, is important for understanding the business cycle.

Q: Another important point you have made in “Household Debt and Business Cycles Worldwide” is the possibility of a Global Household Debt Cycle. What is the Global Household Debt Cycle? Do you think the increase in debt burden around the global is more in sync?

M: This is an area where we think is an exciting area to look into going forward. We just highlighted this one statistical finding in our paper. But I think a lot more needs to be investigated in terms of why we found what we found.

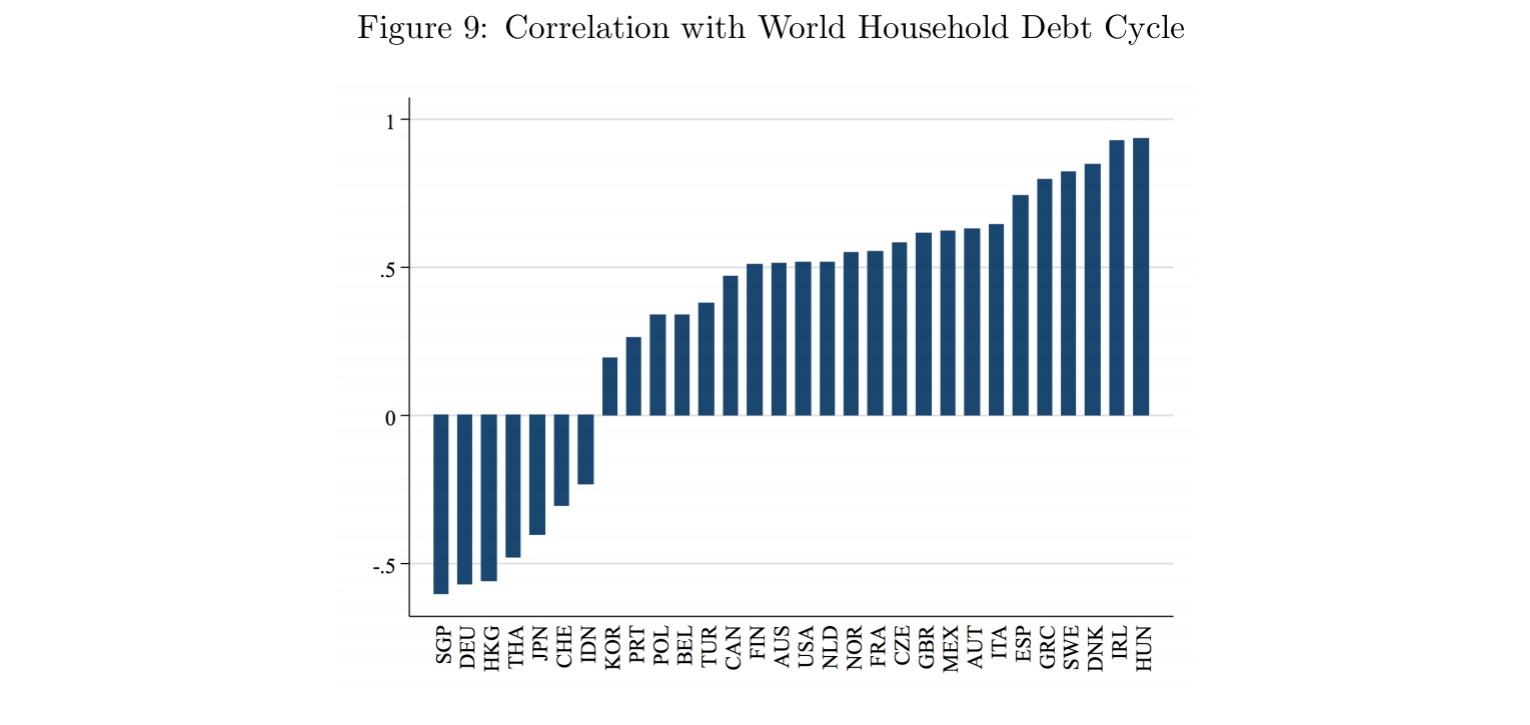

What we found basically is that the credit cycles and its impact on the business cycles happen in a number of different countries, and you see that those cycles in those countries kind of working independently as well. For example, in the peripheral European economies versus core European economies. But at the same time, globally there is a correlation between these cycles. So, in other words, there is a global factor in these credit cycles. There is a common component that tends to happen around the same time across different countries.

There can be good reasons for that. For example, the financial sector is global in nature so that the same shock propagated through the financial sector globally. So, we can expect that these cycles have become more in sync in recent decades. I think that’s a fair interpretation of the data.

But as I’ve said, exactly how much and why the countries have become more in sync? What are the deeper factors that are important for driving these global cycles? I think they are fascinating questions that are being investigated more a lot of academics.

Q: Another rising line of research is about the Global Financial Cycle, which indicates that financial shock in certain core countries will be transmitted all over the world. To me, this line of research is quite like two side of the same coin with your Global Household Debt Cycle. Do you agree? How should researchers reconcile the two lines of thought?

M: I very much agree with your characterization. There is a link between the two. In fact, we try to point that out in the paper you have mentioned. The household credit cycles are very important for the understanding of the business cycles. Those cycles themselves are correlated with that Global credit cycles.

These two questions are very much related. But exactly how and to what extent are these two things related? I think that is precisely the question that needs to be investigated more. But I think it is a very interesting and exciting question for this line of work going forward. We are trying to dive into it as much as we can.

>>> You can follow EconReporter via Bluesky or Google News